Chimps, The Cheshire Cat & The Fall of Tony Blair

National Review Online, May 26, 2005

When, after a great victory, a Roman general marched in triumph surrounded by plunder, captives, and, quite probably, hot chicks, he was always accompanied by a slave whose job was to hiss periodically in the great man’s ear the irritating reminder that he was only human, not a god. Something a bit like this (well, I don’t know about the plunder, captives, and hot chicks) happened to Tony Blair in the aftermath of his party’s triumph in the recent British elections. Within hours of victory, numerous Labour politicians lined up to tell Blair to get lost. Former foreign minister Robin Cook took time out from his usual bilious routine to report on the views of the nation’s boulevardiers. “Anyone on the streets knows we were not elected because Tony Blair was popular....” Another former, a former health minister better known for the elections he has lost than those he has won, said it was time for Blair to go. Former actress and current hysteric, the shrilly leftist MP Glenda Jackson chimed in with the claim that the “people have screamed at the top of their lungs. And their message is clear. They want Tony Blair gone.”

Well, Glenda, in case you weren’t paying attention, the people have just made Tony Blair the first Labour prime minister to win three consecutive election victories. While the party’s parliamentary majority was substantially reduced, it remains, well, substantial.

To the novelist and journalist Robert Harris (an old friend of Blair’s Svengali, Peter Mandelson, but a clear-eyed judge of British politics nonetheless), this all looked like madness: “it does not…require a political genius to see…that it is a thoroughly bad idea for a minority party-cabal to bring down an elected prime minister. The Liberals did it to Asquith in 1915 and have never gained power again. The Tories did it to Thatcher… and have since suffered three successive election defeats… Now Labour, like a chimp examining a loaded revolver, shows alarming signs of the same casual attitude to its political extinction.” Harris noted that an opinion poll conducted shortly after the election had shown some 83 percent of those who had voted Labour said that Tony Blair should stay on for at least another twelve months.

The same poll, however, revealed that over 60 percent of Labour voters want Blair out within three years, an indication, perhaps, that all is not rosy for Tony. And it’s not. Take a closer look at the stats: the Labour party’s share of the vote, a dodgy postal ballot or two over 35 percent, was the lowest enjoyed by an incoming government for nearly 200 years, and impressive as Labour’s haul of parliamentary seats undoubtedly was, it came in at well below the total secured in the previous two general elections. The number of votes cast for the party has slumped by a third since the 1997 election that swept Blair into power. For the first time in a decade, many Labour MPs are sweaty, anxious, and paranoid about their parliamentary futures, something that bodes ill for Blair’s.

It seems a long, long while since the bright, confident afternoon that Tony Blair first took possession of 10 Downing Street to the cheers of a supposedly spontaneous jubilant flag-waving crowd (in fact Labour-party workers and their families, but never mind). Years of spin, manipulation, and dishonesty, made all the more grating by relentless prime ministerial preachiness, have made Blair a deeply distrusted figure, part curate, part conman, all charlatan. Of course, there’s nothing new about the British loathing a repeatedly reelected prime minister—there were few politicians so disliked as Mrs. Thatcher at the height of her powers—but Blair has to contend with a threat that never really troubled the Iron Lady: the Labour party.

Once firmly established in Number Ten, Mrs. Thatcher could always rely on the adulation of her party’s rank-and-file and, until the Gadarene meltdown of November 1990, her MPs. Tony Blair cannot. As Labour leader he has filled an abattoir with the slaughtered sacred cows of party orthodoxy. This has won him elections, but lost him the love, affection, and loyalty of his activists. They, poor souls, remain trapped in a mindset that blends traditional working class belligerence with the idiot radicalism of a third-rate provincial university. To them, Tony is the outsider, the toff, Bush’s poodle (pick your insult), a necessary evil to be tolerated only so long as he brought in the votes.

And that means that Blair is now looking very vulnerable indeed. At the election Labour lost most ground in those parts of the U.K. where his emollient appeal had once been greatest. The affluent southeast has largely returned to its Tory roots. In England itself more voters opted for the Conservatives than for Labour. Labour is once again dependent on its traditional heartlands, the industrial north, and those grim socialist satrapies better known as Scotland and Wales, territories where Blair’s message has very limited intellectual, emotional, or electoral appeal.

Compounding his weakness, Blair has already said that he will resign before the next election. Quite why he chose to hobble himself in this way remains unclear. It’s probably best to ask Blair’s chancellor of the exchequer (finance minister) and presumed successor, the sulky, scowling, and increasingly impatient Gordon Brown. In circumstances that have been obscured by controversy, mystery, and mudslinging Blair may (or may not) have promised to step down in favor of Brown at some time during his first term and he may (or may not) have promised to step down in favor of Brown at some time during his second. He may also have sold his chancellor the Brooklyn Bridge, a secondhand Pinto, and a three-dollar bill. Who knows? In any event, it’s 2005 and Blair’s still in office, but the trusting Mr. Brown has finally and painfully come to the same conclusion as the rest of the country. “There's nothing,” he told Blair, “you could ever say to me now that I could ever believe."

Eventually, Blair did what he always does (or may not have done) on the previous occasions that he needed to keep Brown onside: He promised to stand down at some point in his next term, but this time, there was a difference. He made that promise in public. The moment he did, the game was up. Politicians at Westminster, a British journalist told me, know that Blair is mortally wounded, “they can see the trail of blood all across the lobby floor.” Power, sycophants, and the ambitious are all ebbing from the prime minister, as Gordon Brown, whose fondness for some of old Labour’s more numbskull pieties has already made him the party’s darling, painstakingly cements his hold over the constituencies he will need to assure him the premiership, a union leader here, a key MP there, a friendly journalist here, a member of the House of Lords there. According to some estimates there are now three times as many Brownites as Blairites within the ranks of the parliamentary Labour party.

Superficially, Blair’s actions since the election seem to show that the maestro has lost none of his touch. The usual crop of meaningless, destructive, and plain dumb "reforms" have been announced, the House of Lords has been stuffed with another batch of cronies, dubious government appointments have been made and dissidents have been roughed up at a parliamentary-party meeting. But this is all flim-flam, flash, and empty glitter, a show that signifies nothing. A better indication of where power now lies comes from the fact that Blair was unable to push through many of the personnel changes he wanted in his new administration, a deeply humiliating rebuff for any newly reelected prime minister, let alone one who has been in office for the better part of a decade.

And the misery doesn’t end there. Blair has for a long time delegated large amounts of the domestic agenda to his chancellor (that was part of the agreement between them), but now, after Iraq, even his hold over foreign affairs is palsied, feeble, and pointless. Britain’s EU policy is a shambles, and so far as the threat from Islamic extremism is concerned, the idea that Blair could bring his party with him alongside the U.S. in doing anything that lacks the approval of the "international community," Hollywood, the Guardian and the New York Times is absurd. All that is left to Blair now is the peddling of a grandiloquent, if benign, idea—saving Africa—ripped off from a rock star.

The next step in Blair’s decline will be guerrilla warfare> against his government from the Labour Left, but this will not be enough to unseat him, and nor, probably, would Brown want it to. Despite a history of awe-inspiring and entertainingly destructive temper tantrums, Brown, like Harris, clearly understands that a coup could come at a terrible electoral price. He has resisted the temptation to play Brutus in the past, and he will do so again. He wants to inherit a united party. Ideally Brown wants that “smooth and orderly” handover that Blair is always talking about, but sooner, please, please, sooner, please, please, sooner, rather than later. So when might that be? Before the election, conventional wisdom was that Blair would oblige his impatient heir about three years into his final term, now the talk is that he might quit next year.

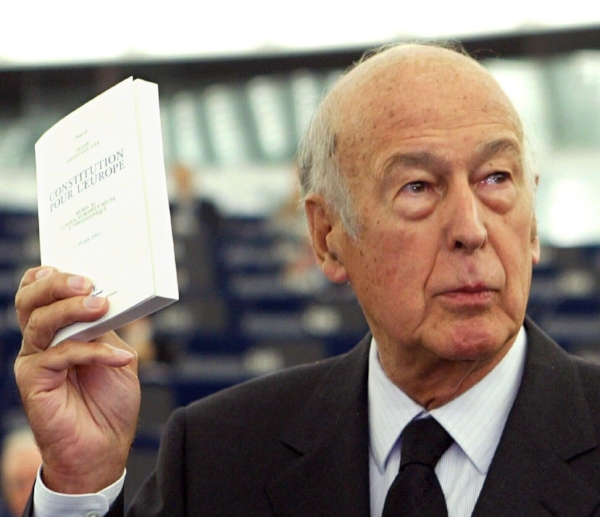

The problem is that there is still no obvious moment for Blair to go. Given his druthers, the prime minister, who is still only 52, would probably prefer to soldier on up to the last minute or, quite frankly, beyond. If he does have to go, this most theatrical of politicians will want it to be on a high note. The conundrum for Blair—and Brown—is that there aren’t many potential high notes around. It’s long been mooted that Blair should resign after tricking the Brits into voting for the EU’s draft "constitution" in the autumn of 2006, but so far his stubbornly euroskeptic countrymen show few signs of playing along. Of course, a British "no" might also signal the end of Blair’s show, if not quite so gloriously as he would have wished. Needless to say, all this may soon become academic: If the French and the Dutch reject the constitution in the next week any British vote may be shelved indefinitely.

The British economy won’t be much help either. After eight years in office, it looks as if Labour is finally going to have to start paying the price for the way in which it has squandered the golden inheritance of the Thatcher-Major years. Quite how this will reflect on Gordon Brown, as Chancellor the man most responsible for the coming mess, is hard to say, but increasingly unappetizing economic news will mean that Blair’s departure will look more like an exit from the scene of the crime than the glorious finale of which he must dream.

So nothing’s certain other than months, and perhaps, years of intrigue, febrile speculation and plots as Blair’s premiership fades, fades, and fades away until, like a New Labour version of Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, all that will be left is an oddly compelling smile, faint, strained, and insincere.