A Hemp Museum

National Review, June 3, 1996

Cannabis Museum, May 1996 © Andrew Stuttaford

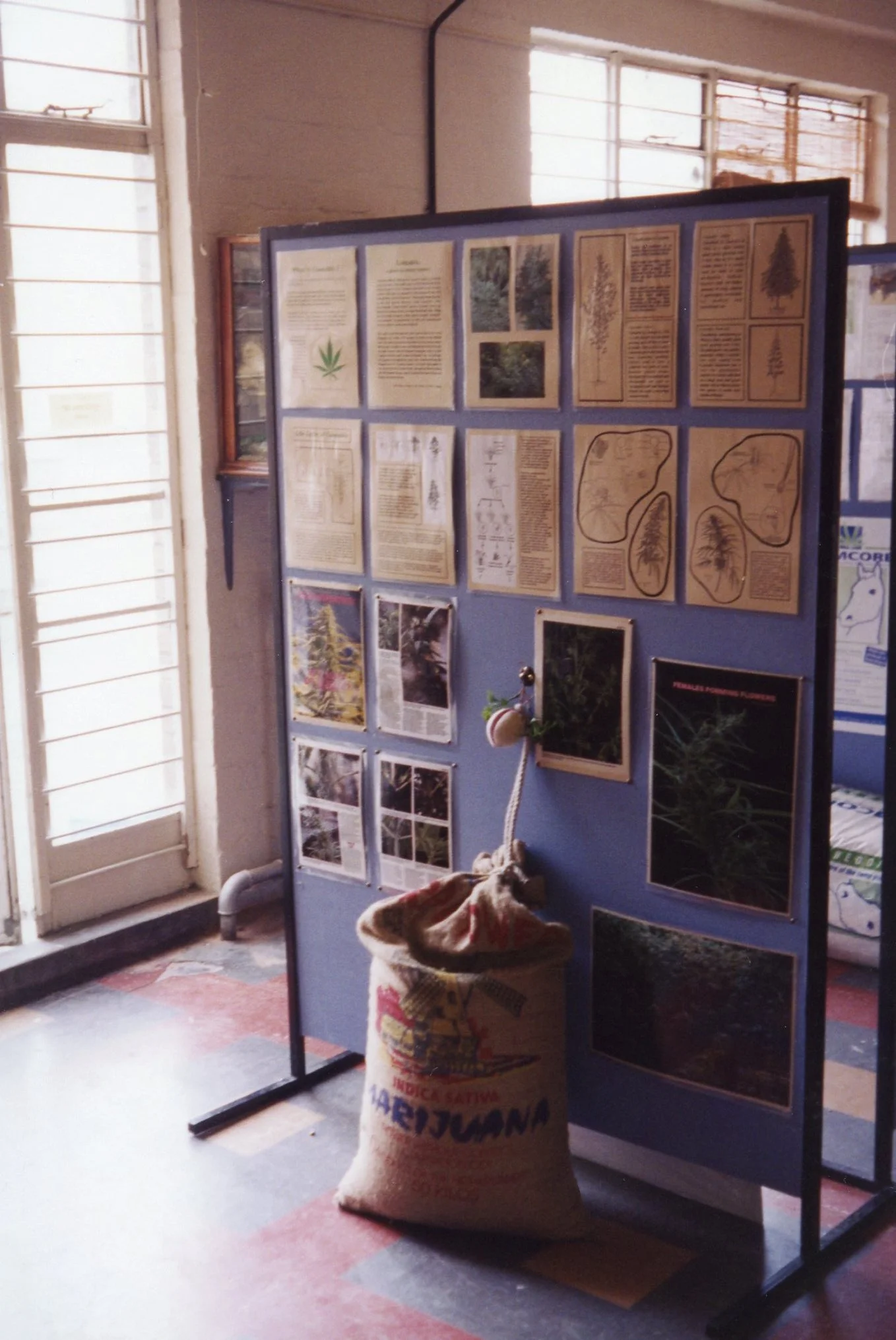

The streets of London, they used to say, were paved with gold. Maybe that is true of the City, the British capital's financial district, but take a walk five minutes to the east, to Shoreditch, and the surroundings are more mundane. Here you will find a theme park of pre-Thatcher Britain. The pub at the end of Redchurch Street is no exception. A drab spot despite its exotic dancer, the White Horse sports a cautious sign noting that Shakespeare is reputed to have drunk there. But if the White Horse is timelessly East End, the East End is itself changing. Not so long ago Redchurch Street was part of that old stereotypical London of the Ealing comedies and the kindly bobby. Now it is also home to a mosque, a Bengali grocery store, and, most recently, a cannabis museum. Located in a nondescript office building, the museum was opened amid some fanfare in April. Howard Marks—a graduate of both Balliol College, Oxford (politics, philosophy, and economics), and the American prison system (cannabis smuggling)—was the guest of honor. The press came, and so did the police. There are, of course, drug laws in Britain, and a wide range of "hemp" products was on display. Hemp? The police were wise to that alias. Hemp is also known as Cannabis sativa, a name it received, somewhat alarmingly, from the Emperor Nero's surgeon. No contraband was found, however. The hemp jeans passed muster. Even the revolting "Hemp 9," a "high energy protein mixed seed bar," was allowed. British law permits the manufacture of hemp products so long as they contain no more than 0.3 per cent tetrahydrocannabinol, hemp's narcotic element. Smoking a hemp T-shirt would be a waste of time; even Bill Clinton could inhale.

The police left satisfied, as well they might. For Redchurch Street is the acceptable face of cannabis. Part Ripley (George Washington grew it! Queen Victoria took it!), part agitprop vehicle, the museum is relentlessly upbeat. It is, after all, run by CHIC, the Cannabis and Hemp Information Club. The aim is to "inform and educate people about the history and many uses of this incredibly versatile plant."

Cheery, if occasionally misspelt (a side effect?), posters accentuate the positive. Cannabis, it seems, can be turned into mighty ropes, excellent paper, and an ecologically sound fuel. It can be used to treat glaucoma and relieve the nausea associated with chemotherapy. Fans of the former British foreign minister will be glad to know that cannabis "hurd" (its inner stalk) can be mixed with lime and water to produce a building material more durable than concrete. Finally, and this is a clinching argument in an era of anxious English mealtimes, hemp might make a healthier animal feed. Given that Britain's maddened cattle seem to have been subsisting on abattoir sweepings, this must be right. There have, after all, been no cases of stoned-cow disease.

Cannabis Museum, May, 1996 @ Andrew Stuttaford

CHIC makes an impressive case. Cannabis does indeed seem "incredibly versatile." So versatile, in fact, that visitors may feel a vague sense of resentment against this leafy overachiever—until, that is, they discover its little weakness. Cannabis is, as one display notes, also "a social intoxicant," safer perhaps than some of those available at the White Horse, but an intoxicant nonetheless.

And this, of course, is the source of the problem. It is the intoxication that enrages an officialdom that once warned (in a possibly misguided approach), that cannabis could lead to "weird orgies, wild parties, and unleashed passions." It is the intoxication that interests users. No one would risk jail time for something that was just a building material. It is unlikely that there will ever be, say, a stucco museum on Redchurch Street. With consumers enthusiastic and governments appalled, disaster was inevitable.

Cannabis Museum, May 1996 © Andrew Stuttaford

Sure enough, the saddest section of the exhibit describes the progress of the American war against cannabis, a miserable saga of mounting ferocity and futility. Prison photographs of the detained line the walls. They pose awkwardly with their families, standing in front of backdrops painted to give an illusion of somewhere, anywhere, other than the penitentiary. The faces, carefully selected no doubt, look innocent, and the injustice on display appears horrifying.

Wisely, perhaps, there is no discussion of cannabis's rougher associates: London will have to wait a while for a crack museum. The connection between the use of cannabis and of other drugs is never explored. Does one lead inexorably to the other, or are rising rates of hard-drug consumption an inevitable consequence of prohibition? NR discussed these sorts of issues a few weeks ago, but its rational approach would not win many friends in Redchurch Street. The museum's amiable staff may have been born too late for Woodstock, but they are hippies pur et dur, albeit with a Nineties twist: "Please respect our No Smoking policy."

Hippies were never too keen on logic. The positive impact of much of the exhibit begins to dissipate the moment one is told that smoking grass is part of the "permaculture." Indian spirituality makes its inevitable appearance. Wasn't that a poster of Ganesha, elephant god and popular head-shop deity, on the wall? Zany politics are also on view, most prominently in the shape of a large, unfinished, papier mâché display, in which a clumsily executed factory appeared to be menacing idyllic pasture. As artworks go, it was a shambles, but the message was clear: Industry is bad. We need to return to a simpler life, and hemp would show the way. "Industry" had, it was argued, played no small part in the banning of cannabis in the first place. There had, surprise, been a conspiracy. DuPont, no less, had been a force behind the original anti-cannabis legislation for commercial motives of its own (bleaching chemicals for pulp—it's a long story). As CHIC explains, "It is only when governments stop protecting the interests of the multinationals that we will be free to benefit fully from cannabis."

Well, maybe, but it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the museum's case for cannabis is getting muddled at this point. Some environmentally flavored Marxism seems to have been thrown into the mix. It does not belong there. At its core the argument for legalizing cannabis ought to rest on a fairly restrictive view of the rights and capabilities of government. This is not an approach normally associated with the paranoid Left—or the EPA, for that matter. A commissar is still a commissar, even if he does drugs.

Maybe this is just carping and the confusion is to be expected. We live, after all, in an absurd time, when even the medicinal use of cannabis is prohibited. An honest discussion of drug policy seems all but impossible. The Cannabis Museum does at least raise some serious questions. Perhaps it is too much to expect more. Since only the bravest politician will question prohibition, debate has, with notable exceptions, become the preserve of the eccentric and the obsessed. Meanwhile, drug-related problems worsen and the official approach will continue unaltered, unsuccessful and ugly.

Sadly, it will take more than CHIC to change this.