The Slow & the Dead & Other Authors

Machado de Assis - The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas

Kathryn Scanlan - The Dominant Animal

Kathryn Scanlan - Aug 9 - Fog

Doon Arbus - The Caretaker

The New Criterion, November 1, 2020

There’s something suitable, in this year gone awry, that the best novel I have read in 2020 purports to be an autobiography written from beyond the grave (“I am not exactly an author recently deceased, but a deceased man recently an author”) and that it was first published in 1881 (after appearing in installments in the Revista Brazileira). With 2020 being 2020, The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas) has been rendered from Portuguese into English not once, but twice, even if it has been read by me not twice, but once. The New Criterion arranged for me to be sent a copy of the Penguin Classics version, which has been translated by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux and boasts a perceptive foreword by Dave Eggers. That this is a paperback, and a rival (translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson) was only available in hardback was, I am sure, merely a coincidence.

In addition to her translation, Thomson-DeVeaux provides detailed and highly informative endnotes, an attempt, she writes, to restore “the book’s malevolent grace and depth . . . in its fullness,” not least the “jokes half-buried in the sands of time.” And she takes pains to stress that she has used endnotes, not footnotes:

Because the Posthumous Memoirs—as befits the creation of an ex-typographer—is exquisitely aware of its existence as a book, commenting on bindings, capitalization and so on, and nowhere does Brás indicate that his grave-composed masterpiece has anything marring its lower margins.

By contrast, Jull Costa and Patterson descend to footnotes. Barbarians.

In Thomson-DeVeaux’s hands, the text—written, says Brás, “with the pen of mirth and the ink of melancholy”—rolls (often) merrily along, playful, acid, and with a liveliness impressive in an “author” so dead:

I was accompanied to the cemetery by eleven friends. Eleven! True, there had been neither letters nor announcements. What’s more, it was raining . . .

There are asides, wild digressions (two pages on a random butterfly), absurd speculation (“Have you ever meditated on the purpose of the nose, beloved reader”?), and erudite allusions. The fourth wall is repeatedly reduced to rubble, thus:

I am beginning to regret that I ever took to writing this book. Not that it tires me; I have nothing else to do. . . . But the book is tedious . . . it bears a cadaveric grimace; this is a grave defect, and yet a minor one on the whole, for the book’s greatest flaw is you, reader. You are in a hurry to grow old, and the book moves slowly; you love direct, robust narration and a smooth and regular style, and this book and my style are like drunkards, they veer right and left, stop and go, grumble, bellow, cackle, threaten the skies, slip, and fall . . .

Deepening the suspicion that Tristram Shandy is chatting to Brás in the afterlife, there are games with punctuation and layout, although Eggers warns against overplaying how innovative The Posthumous Memoirs were:

Readers are an amnesiac species, and so, every few decades, we wake up to believe that an author addressing the reader directly, or playing with form, or including references to the author or the book within that book is new and should be labeled post or meta- or whatever unfortunate and confining term will come next. But the fact is that an outsize number of the classics of the world employ one or many of these so-called post/meta devices.

That the writers Eggers cites in this context who precede Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1839–1908), the real author of The Posthumous Memoirs, are Cervantes, Sterne (an influence acknowledged by Machado), Voltaire, and Austen is an indication of the heights that this book, written in Brazil by the son of a man whose parents were freed slaves and an Azorean washerwoman, manages to reach.

Machado’s ascent began with a job as a typographer’s assistant, followed by journalism and then increasingly important positions within the civil service, something he combined with a growing literary career. He was a cofounder of the Brazilian Academy of Letters in 1897, becoming its first president, a post he held until he died. For him to have risen so far in a racially stratified society where slavery was finally abolished only in 1888—seven years after the publication of The Posthumous Memoirs—as, for those keeping count, a “quadroon,” made his achievement all the more remarkable.

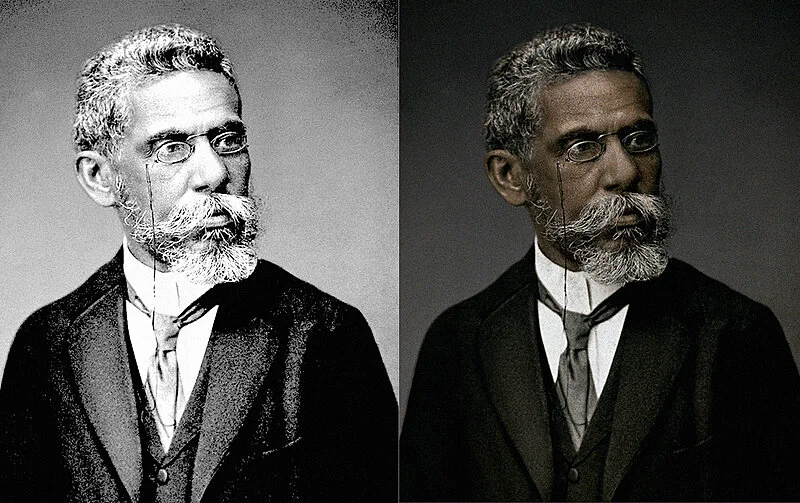

Tellingly, the best-known photograph of a man who was by then a significant Brazilian cultural presence appears to have been lightened, and he was labeled as white on his death certificate, two signs of the implicit challenge that Machado posed to the racial hierarchy, a challenge, now explicit, that is the subject of lively debate in Brazil today.

Perhaps it’s simplest to note the observation by the University of California’s Professor G. Reginald Daniel that “essentially, Machado was an insider who remained to some extent a detached observer—an outsider.” By the time Machado wrote The Posthumous Memoirs, he had penetrated the elite, and he uses his knowledge of its workings to depict the milieu in which Brás (who never had “to earn [his] bread with the sweat of [his] brow”) had lived a generation before (Brás is described as having died in 1869 at the age of sixty-four). But that detachment is not hard to see: When Brás has (at last) been elected to the Chamber of Deputies, the only contribution he mentions having made is a speech (praised for “its bursts of eloquence [and] literary and philosophical elements”) to reduce the size of the National Guard’s shakos. It changes nothing, despite his accommodating suggestion that such an alteration could be delayed “for some years” and confined to “three-quarters of an inch, or even less.”

Slavery is part of the backdrop to The Posthumous Memoirs—given the time and place, it could not be otherwise—but in a matter-of-fact manner, going almost entirely without editorial comment, reflecting Machado’s public reticence on the topic. That reticence, however, has been overstated, and here too there are hints of a more critical attitude. But as Machado was writing in the character of a cynical, caustic, and (in a loose interpretation of that term) nihilist member of a ruling class that had prospered under slavery, little more, perhaps, could be expected, other, maybe, than the absence of illusion. Even in that, Brás, too willing to find a rationale for brutality, disappoints on more than one occasion, a flaw that in Machado’s hands is unlikely to be an accident.

To take one example, strolling through Valongo, the site of an old slave market in Rio de Janeiro, a location that Machado will not have chosen at random, Brás encounters Prudêncio, his former “slave boy,” who, as a child, he had ridden like a horse, “put[ting] a bit in his mouth and thrash[ing] him mercilessly.” Now a free man, Prudêncio is beating a slave whom he has in turn bought. Brás orders Prudêncio to stop. Contemplating the incident later, Brás concludes that it was “dreadful, but only on the outside,” a qualification that says a lot both about Brás and of Machado’s view of his own, well, I hesitate to use the word, “hero.” But then, Brás continues, “as soon as I slid the knife of reasoning farther in, I found a marrow that was mischievous, refined, even profound,” adjectives that are subverted by his analysis: “This was Prudêncio’s way of freeing himself from the blows he had received—by passing them on to another.” The chapter in which this occurs is called “The Whip.”

About the only thing that Brás takes seriously is his relationship with Virgília, the woman he has failed to marry (as he fails to marry anyone)—despite their first exchange of glances being “purely and simply conjugal”—but with whom he carries on a lengthy affair after she marries Lobo Neves, the man who stole her away from him in the first place.

The first and second times he meets her after her marriage, they exchange a few words, but on the third:

We waltzed, and I won’t deny that as I held that supple, magnificent body next to mine, I had a singular sensation, that of a man who has been robbed.

Neves never stood a chance:

I was known as a master waltzer.

Some weeks later:

BRÁSCUBAS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . !

VIRGÍLIA

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . !

Although centered on Brás’s involvement with Virgília, the book’s narrative is chaotic, its herky-jerky pace underlined by its division into 160 chapters, each named—“Sad, but Short” is followed by “Short, but Happy”—over the course of fewer than three hundred pages. Chapter CXXXVI is entitled “Uselessness.” In its entirety, it reads: “But, either I am very much mistaken, or I have just written a useless chapter.”

If The Posthumous Memoirs contains any message, it is, to optimists, dark. Thus, a sick, delirious Brás believes that a talkative hippopotamus takes him to the top of a mountain from which he watches all of history unfold in a bleak procession:

And then man . . . would run . . . after a nebulous, elusive figure cobbled together out of scraps, a scrap of the intangible, another of the improbable, another of the invisible, all sewn with flimsy stitches by the needle of the imagination; and this figure—nothing less than the chimera of happiness—either fled constantly or allowed itself to be caught by its train, upon which man would clasp it to his breast, and then the figure would give a scornful laugh and vanish like an illusion.

Much the same could be said of an early love, the mercenary Marcela, who loved Brás for “fifteen months and eleven thousand milréis” (several hundred thousand dollars today; Brás’s father was right to be annoyed). Here is another failure in what Jull Costa and Patterson in their introduction to The Posthumous Memoirs describe as “a catalogue of failures,” not just by Brás, liberated by death to admit to his own mediocrity (“What an unburdening!”), but by a number of the book’s main characters. It’s an accurate description, even if Eulália, a potential bride, can hardly be blamed for failing “even to live past seventeen,” a failure brought on by yellow fever and not made any easier by the fact that it is exaggerated by a typo that would have amused Machado the writer and infuriated Machado the typographer: in the book Eulália makes it to nineteen.

In 1857, Thoreau counseled a friend that there was no need for a story to be long, “but it will take a long while to make it short,” advice that in various forms has been circulating for centuries. Kathryn Scanlan would understand. She spent over a decade working on the forty short, short stories that flicker across the 140 pages or so of The Dominant Animal. Her sentences are whittled down and polished to some kind of perfection without the work that went into them ever being the point. They are not, mercifully, a display of self-consciously fine writing, but are matter of fact, underwritten rather than over, and often, carefully, and most precisely, unsettling:

The baby is difficult to figure. It sounds like a nest of squirrels I found after a storm. One of them had died in the fall from the tree, and the other two chattered next to it, to me, as though to tell me of their trouble. I understand the inappropriateness of comparing a human baby to a squirrel baby. I don’t know why I continue to do so. I cannot help it that a human baby also reminds me of an overfull helium balloon hovering too close to a hot bulb.

If anything unites these tales, it is the sense that they are sightings of a world slightly askew, a world that is not quite ours, but which shares its unhappiness and cruelty too regularly for comfort. Here and there the stories shade—no more than that—into something close to horror, but more frequently they just leave a feeling of unease. Most need reading more than once, and some remain ambiguous, even on occasion seemingly incomplete, from time to time frustratingly so, a device, conceivably, to reinforce and prolong the reader’s disquiet, to ensure it lingers in the mind.

The way that speech slides unpunctuated into the narrative adds to the impression of being in a space where boundaries have broken down:

Bob Snatchko held a painting of yellow flowers in dirty snow. Looks like we had a genius on our hands, he said. What a tragedy! Are these things worth more now that he’s a confirmed nut job?

Some pie on your chin, Bob, I said.

And yet it is a distinctly American space. Bob Snatchko. Pie. Scanlan, I note, grew up in Iowa.

As to what these stories are about, it is tricky to generalize, other than, perhaps, that they often depict relationships that have gone sour, or perhaps always were—sometimes it is hard to say. Among the topics we find a picked-on eccentric, an unnerving surgeon, an embittered daughter in her mother’s last days, tenants from hell, an old man’s life in three pages, a murder certainly, a murder possibly, an unfaithful dog, the ideal carpet, an annoying husband felled by a golf ball, neighbors observed:

[I]n the small hours of the morning, one son is chasing the other in the yard with a pair of scissors. It is early enough that we could be dreaming it, the half-clad boys running and tumbling like satyrs in the blue light of the lawn.

On the cover of The Dominant Animal, Scanlan is described as the “author of Aug 9—Fog.” Left unsatisfied by forty short, short stories, I turned to Amazon. Published in 2019, close enough for a 2020 review, I reckoned. It was worth the clicks. Spare, elegiac, and curiously haunting, and somewhere between poetry and prose, Aug 9—Fog is elaborately unvarnished. It was also co-written, one way or another, with Cora E. Lacy, a woman from a small town in Illinois who died in her mid-nineties over forty years ago.

In a note at the beginning Scanlan explains:

The text that follows is drawn from a stranger’s diary. I acquired the diary fifteen years ago, at a public estate auction. It was among the unsold items. I removed it from a box on its way to the garbage . . . . The diary was a Christmas present to the author from her daughter and son-in-law. . . . [The diarist] was eighty-six years old when she began recording in it. . . .

I didn’t try to read it. I kept it in a drawer. I assumed it illegible.

But then I did read it—compulsively. . . .

As I read, I typed out the sentences that caught my attention. Then, for ten years, off and on, I played with the sentences I’d pulled. I edited, arranged, and rearranged them into the composition you find here.

Ten years. Scanlan takes her time.

The diary covers the period between 1968 and 1972, but Scanlan has removed the dates and simply divided the book into Winter, Spring, Summer, Autumn, and then one final Winter.

On September 1 this year, Scanlan retweeted a call by the Canadian poet Anne Carson to “edit ferociously and with joy, it is very fun to delete stuff.” It is evident both from The Dominant Animal and Aug 9—Fog that Scanlan does just that. But in the latter work, she preserves as she destroys, stripping down what she concedes can be a “terribly banal” text in a fashion that allows the essence of Cora—or the essence of Cora as envisaged by Scanlan—to emerge, with Scanlan reshaping an everyday existence into something of beauty, and, as she does so, summoning up a time that now seems impossibly remote:

So snowy & bad he came back. Beautiful big red sun dog on the North. D. played her Victrola. Vern working on Doris cupboards.

Cora wrote in the vernacular of her era, and her grammar (frequently) and spelling (sometimes) are shaky, but reproducing them comes across not as patronizing but operates instead as a way of bringing her back to life. As I read, I could hear Cora, or at least form a clear view of how she might have sounded, or, again, of how Scanlan thought she might have sounded:

D. & I walked over to Bertha’s to see her flowers. We had teas, cookies & candy, legs kind a tingly when we got home.

Scanlan writes in her introductory note of how “the diarist’s voice, her particular use of language, is firmly, intractably lodged in my head. Often I say to myself, ‘some hot nite’ . . . . I have possessed this work so thoroughly that the diarist has ceased to be an entirely unique, autonomous other to me. I don’t picture her. I am her.”

But in an article for The Paris Review in 2019, Scanlan qualified that statement by saying that its last line

portrayed the mindset in which my book was composed. My creation was possible because the essential mystery of the diary opened a space in which I could imagine an “I” who was other, but also myself—otherwise known as the realm of fiction. My book would not exist without that space, without that leap of voice. . . .

But then, last year, before my book went into production, I tried one last search for the diarist. I needed to know whether she had any surviving relatives. If she did, I wanted to contact them. This time, one result came up in my browser: the diarist’s full name linked to a page on a website called Find a Grave.

Now she discovers (as she probably always could have done; Cora had lived less than an hour away from Scanlan’s parents, and she’d put her name and address in the diary) fact after fact about the real woman, her life, her death, her family: “Here was Lee, her brother. Here was Bayard, her sister’s husband. Here was Bucky, her niece’s son.”

And:

As the real woman expands in detail, the private one shrinks. Presented with the stark, unequivocal details of the real woman’s life and death, the private woman undergoes a death of her own.

I am glad to have found the diarist’s relatives, glad to be able to share the diary and Fog with them. But the price of this is a puncture, a deflation of the reality—or unreality—I’d made. It feels like an origin story in reverse: in finding the woman, I’ve lost the woman. Face to face with a photo of the diarist’s grave, I was forced to realize I was not, in fact, her—was not now, had never been. It had been me all along.

Yes, I would say, and no. Scanlan’s Cora is an artifact, something underlined by how painstakingly produced Aug 9—Fog is, from its elegantly plain cover to its pages laid out with only a few lines of text (“Ruth came thru operation. Hiller’s house burned. We went out to see what fire had done. Sure clean sweep”), but the real Cora is unmistakably there too.

Cora was eighty-six when she started the diary. She enjoys her quiet pleasures, painting, a jigsaw (“Niagara Falls. Very pretty, hard one”), Scrabble, some photography, watching the outdoors (“Robin on nest today”), but twilight is never far away:

Big snow flakes like little parasols upside down. Ella had Widow’s Club to dinner, a delicious fried chicken at Holiday Inn. D. & I out to cemetery little bit.

There are aches and pains (“my right knee ailing”); people retire (“they gave her a beautiful clock”), fall sick (“Maude was operated on this A.M. They took out tumor in bladder it was cancer”), and die (“Vern took worse. Passed away before D. got there. Seemed to just sleep away”). Not long later, Nora complains that her “pep” has left her, but, a Midwestern stoic, she soldiers on.

Scanlan writes that the “diary still moves me, which seems unbelievable.” Not really.

I am the son of a collector and a collector myself, in my case stamps (a standard gateway drug half a century ago), political ephemera, Russian icons, First World War art, old maps, preferably of the Baltic region, a Pickelhaube, and, of course, books, including, when it comes to the fiction section, several novels—some of my favorites—that revolve around collecting, accumulation, and people’s relationship with things. Bruce Chatwin’s Baron Utz makes his inevitable appearance, but so does Thomas Clerc obsessively chronicling his possessions in Interior (reviewed by me in The New Criterion of May 2020) and Christine Coulson’s beguiling Metropolitan Stories (reviewed by me in The New Criterion of November 2019), in which the Met’s artworks, employees, and visitors conduct their own enchanted dance. And then there’s the fictional Henry James Jesson III, the bibliophile and collector from Allen Kurzweil’s The Grand Complication, whose immaculately arranged hoard has room for the unpredictable as well as the respectable: a “severed finger, the gruesome harvest of a Calvinist surgeon who collected anomalous body parts.”

So the premise of The Caretaker by Doon Arbus (a daughter of Diane) was one that I would never have found easy to resist. Its eponymous but unnamed protagonist looks after the unprepossessing Manhattan building that houses the collection of the late Dr. Charles A. Morgan (the author of Stuff—A Meditation on the Charisma of Things). In life, Morgan had run the house as his own museum (one reason Mrs. Morgan had moved out), and he used his will (a document that demonstrated “that he cared more for the fate of his building and its contents—to which he had devoted himself for nearly half a century—than for any living creature”) to ensure that it would outlive him.

Mrs. Morgan, who had remained his wife if not his cohabitee, presides punctiliously over her late husband’s legacy: “His absence,” claims Arbus, not always the most trustworthy of narrators, “healed the rift.” After learning that the new widow “insisted that the objects to be enshrined were not limited to the items in Morgan’s collection, but included anything he might have touched, worn, used, sat upon or gazed at before leaving home for the last time,” however, I wasn’t so certain about that.

Other members on the Morgan Foundation’s board shared this doubt. They “protested that treating Morgan’s personal commonplaces with the same reverence accorded the collection’s artifacts would be to make a mockery of his life’s work.” Judging by what is on show in a hallway near the museum’s entrance, they had a point:

At first glance, the display looks not so much haphazard as deliberately organized to confound comprehension. Ordinary domestic items (a wire hanger, a chewing-gum wrapper, locks with and without their keys, a broken hinge, a watch without a watchband, a toilet plunger, a plastic coffee lid) vie for position with a smattering of gilt-framed eighteenth-century oil portraits, a large multifaceted jewel, an African mask of teak and straw, a pair of pearl-handled dueling pistols aimed at one another. Nature has its place here too: seashells, dried leaves, driftwood, lumps of coal, a human skull.

The Dürer, hung “amid a cluster of various small household objects,” is elsewhere.

The caretaker, an intelligent if complicated man, is hired—it seems at the insistence of the widow, “his perplexingly loyal advocate”—despite a résumé of downward mobility, false starts, abandoned promise, and a bewildering range of mainly unimpressive jobs briefly held, “a process of divestiture that bore a disconcerting resemblance to flight.” On the plus side, as a young man, he discovered Morgan’s Stuff: “Its method of deciphering hidden relationships between things in a world apparently bereft of meaning offered him a lifeline; he [had] declared himself a disciple.” Poor judgment, maybe, but not the worst qualification.

In reading the early portions of this book, my guess was that the caretaker, a Bartleby who had finally found something he would rather, was going to be absorbed into the museum—an institution that owes a third of its (few) visitors to the fact that they have confused it with the Morgan Library uptown—not necessarily healthily, not necessarily uncomfortably, perhaps even literally: “He is a monochromatic man. Dust is his color. It envelops every aspect of his person, hair, skin, eyes, clothing, softening all distinctions.”

When the story reaches the present, he has been at his post for over two decades. It is “now the very essence of his identity. He is the caretaker of The Foundation, Dr. Morgan’s man,” there “solely to make the dead man come alive. It has become a consuming preoccupation. His work is never done.” He labors, for the most part alone, reveling in his celebration of what he describes as Morgan’s “meticulously orchestrated . . . conversation among objects.”

At this point, I was anticipating a soothing and diverting read, enhanced by Arbus’s bone-dry sense of humor and made all the more entertaining by a writing style that, in passages of subtle ponderousness, occasionally nods to Henry James, if only as pastiche, as well as Arbus’s satisfying way with lists, reassuringly suggestive of an admirably sharp curatorial focus:

Orphaned objects assembled here like so much scrap are orphans no longer. A child’s worn left shoe bereft of laces, a coil of hemp, a jewel-encrusted Russian Easter egg poised on end, a tarnished ladle with holes punched through its bowl in a star-shaped pattern (presumably to drain off liquid), a glass eye staring helplessly, relentlessly, at nothing, an Indian arrowhead, a small framed pen-and-ink rendering of a dense forest choked with underbrush, the skeleton of an umbrella, a telephone receiver trailing its crimped cord, the displaced Roman nose of a lost marble statue, a fossilized crustacean, a stethoscope, a paper clip, a tortured tree branch, petrified and turned to stone—all members of some complex extended family with their own indispensable roles to play—commune with another across a wasteland of irrelevance, each an answer to the others’ prayers.

Sadly, by the time this glorious catalogue brings joy to the page, the order, however offbeat, that it represents is fracturing, undermined by the combination of the machinations of a changed board with no time for it (the widow has sunk into dementia) and, partly in response, by the actions of the caretaker. His struggle to champion what has possessed him transports both the caretaker and this story to a place where I was no longer sure quite what it was that I was reading.

Almost from its very beginning The Caretaker had strayed far beyond the alternate reality necessary to any novel. But before it arrives at its enigmatic yet oddly poignant conclusion, Arbus takes the narrative into a realm where hallucination, perhaps, a trace of the supernatural, just maybe, and obsession, undoubtedly, are the only keys to the riddle that she, no mean trickster, has conjured up.

And it is made even more disorienting by Arbus’s distinctive voice, calm, wry, deadpan amid absurdity, and yet capable of lyricism at unexpected moments, as when she navigates the widow’s shattered mind:

Every so often, she would emerge from her blighted state to endure a brief glimpse of what she’d lost, which only made things worse, leaving her forlorn, desolate, beached on a strange shore.