Spies Like Us

Joseph Weisberg: An Ordinary Spy

The New York Sun, January 16, 2008

Mark Ruttenberg, the hero of "An Ordinary Spy" (Bloomsbury, 288 pages, $23.95), Joseph Weisberg's deft, sour, and clever new novel of espionage, bureaucracy, and disenchantment, is — it is true — a spy. But he's no James Bond.

Just read what happens, or doesn't, when he shows up for a celebration at the Russian embassy in the country to which, as a novice CIA agent, he has recently been posted. The poor fellow fails to make any real progress with the general who is the most important target in the room, he gets "tipsy" on two shots of vodka, and when, finally, he runs into a girl he has been trying to recruit, he is not only snubbed, but also floundering:

I had an impulse to rush after her, grab her arm, and spin her back around. But I didn't know what I'd do after that. Did I want to kiss her? I'd always found Daisy attractive … [b]ut I'd wanted to recruit her, not sleep with her.

Good God, man, get a grip! In cloak-and-dagger Valhalla, 007 is, undoubtedly, shaking his head (as well as that third martini). The contrast between his stumblebum spy and Ian Fleming's swashbuckling psychopath is, however, one that evidently amuses Mr. Weisberg. As fans of his debut novel, the lovely and beguiling "10th Grade" (2002), will recall, Mr. Weisberg is a sly, dryly funny writer, and even in the far more downbeat surroundings of his new book, he sporadically allows himself to unleash the occasional fleeting and stealthy joke at the expense of the luckless Ruttenberg and the frustrating, dull, drab routines that make his a life far removed from the spy game's glittering, legendary, and deceptive glamour.

But the disillusion, and not only Ruttenberg's, that permeates this book is generally closer to the "quiet desperation" of old Thoreau's loopy ravings than any profound ideological crisis; there is no hint of the majestic decay and mythic exhaustion that run through le Carré's best, possibly because Mr. Weisberg is describing an agent at the beginning of his career — an agent working, what's more, for a nation that, unlike George Smiley's Great Britain, is unwilling to accept eclipse, humiliation, and relegation to the second tier.

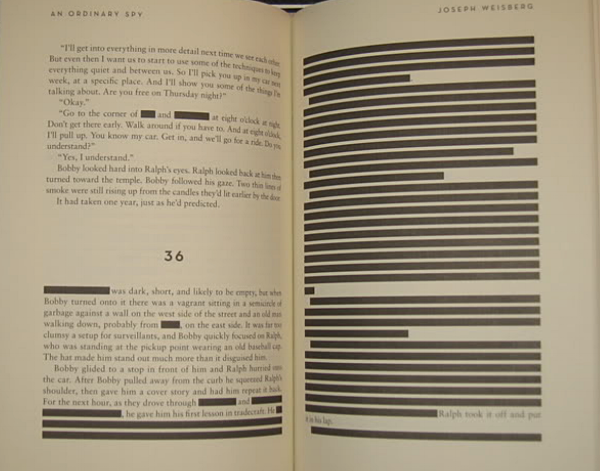

Nevertheless, there are moments when readers of "An Ordinary Spy" may worry that its portrait of the CIA as a cesspit of careerism, groupthink, and deadening conventionality may be a warning that the United States is poised to follow its transatlantic cousin into decline. The fact that the book's author formerly worked for the agency (he was employed there for three years and, by the time he quit, was in training to become a "case officer" much like Ruttenberg) only adds to the concern: Even if he never advanced very far in the intelligence service, Mr. Weisberg must have learned enough to offer up an accurate description of its workings. Whether that is, in fact, what he has done is a different question (I've no idea one way or another), but his writing feels authentic, an impression he tries to reinforce by displaying his text in a "redacted" format that is simultaneously bogus and real. As a former CIA man, he was indeed required to submit his manuscript to Langley's Publications Review Board, but ahead of doing so, he anticipated what the board might ban. Both the board's deletions and his own pre-emptive strikings-out are evidenced by the thick black lines that are the censor's impenetrable spoor, with no way to distinguish between them.

It's a device that sometimes irritates, but it helps transport outsiders into the secret world, at least as they might imagine it, a world made all the more mysterious, all the more opaque, and all the more disturbing by the fact that Mr. Weisberg's readers aren't actually informed where within it they have ended up: The country where the greater part of the drama unfolds is never disclosed. If I had to guess, it's located somewhere in Central Asia, the Middle East, or North Africa, but we're never told for sure.

And maybe that's the most effective device of all. The United States now finds itself enmeshed in a probably endless, possibly apocalyptic struggle against an adversary that knows no limits, no rules, and no borders, a conflict where every diplomatic outpost, but particularly those in countries of the type that Mr. Weisberg doesn't name, is a listening station, a sentry box, and perhaps more. In one form or another, such outposts have existed whenever there have been nations with interests to protect. They have been manned by guards, by observers, and by spies; patriots often, ideologues occasionally, but for the most part, ordinary men doing a job that is rarely extraordinary, and changes history even less.

And it is the story of two of these ordinary men, these ordinary spies, that Mr. Weisberg sets out so skillfully. There's no great message that underpins this novel, no intimations of coming American collapse: just a tale well told of lives that were meant to be spent watching, probing, plotting, guessing, and double-guessing, lives that, it turns out, go somewhat awry, lives that are illuminating only in their insignificance, and yet they are lives on which yours, and mine, may depend.