Two centuries after he was born in the otherwise blameless German city of Trier, on May 5, 1818, Karl Marx is enjoying a moment. He and his writings have had such moments before—many other moments, with all too few intervals, since the 1840s. Most recently, the 2008 financial crisis boosted sales of the old revolutionary’s works, if not necessarily the numbers of those who have read them—not the first time that this has been a problem. In “Marx and Marxism,” London-based historian Gregory Claeys reports that “on first encountering” Marx’s “Das Kapital,” Ho Chi Minh used it as a pillow. Fidel Castro, a dictator made of sterner stuff, boasted of having reached page 370, a milestone that Mr. Claeys reckons was “about halfway”—a fair assessment if we ignore volumes two and three of an epic that often reads better with its pages unopened.

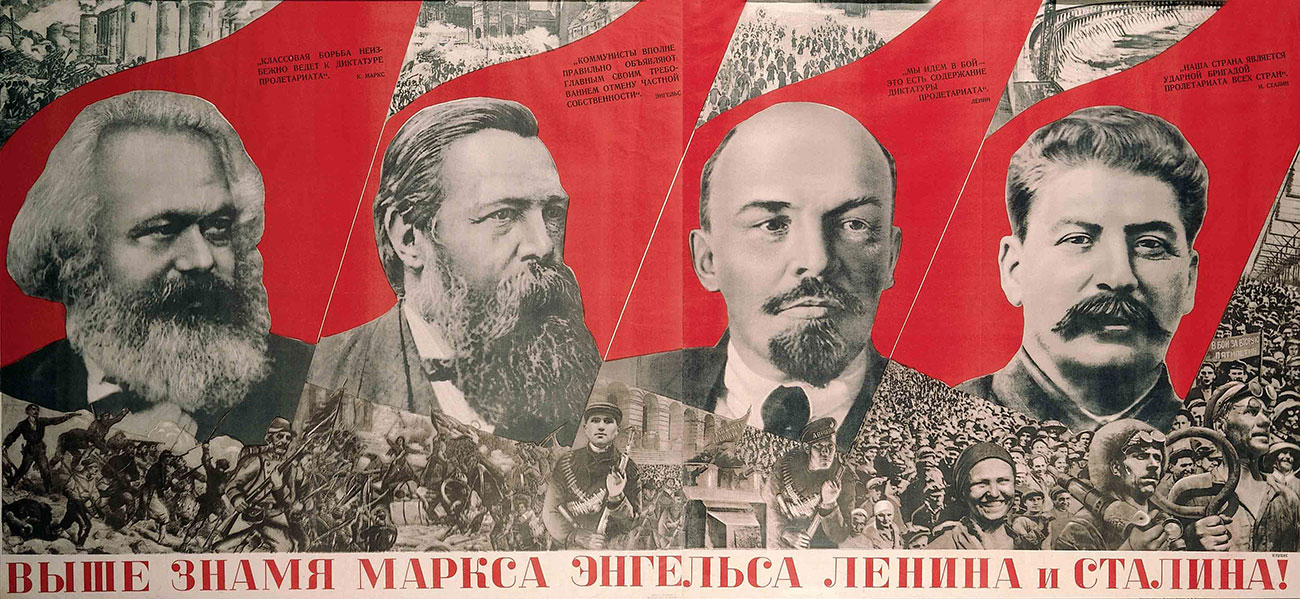

Mr. Claeys presumably timed his book to coincide with Marx’s bicentennial. In China President Xi Jinping, an erstwhile Davos guest star, hailed the anniversary by describing Marx as “the greatest thinker of modern times.” Trier marked the birthday of its most notorious citizen with a conference as well as the unveiling of a heroically styled statue, presented by the Beijing government. Luxembourg’s unmistakably bourgeois Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, turned up in, somewhat ironically, a Trier church to praise Marx’s “creative aspirations” and to absolve him of responsibility “for all the atrocity his alleged heirs have to answer for.” So that’s all right then.

Mr. Claeys, although writing from a position quite some way to the left, does not shy away from the horrors committed in Marx’s name. But he never provides a definitive answer—perhaps no one can—to the extent of culpability a 19th-century philosopher can have for tens of millions of 20th-century dead. In the course of the second part of this book—a brisk survey of Marxism after Marx—Mr. Claeys doubts whether Marx would have supported the Bolsheviks beyond the “securing of the revolution.” But he admits that such a claim “remains contentious.” As for there being any continuity between Marx and “the official ideology of the Stalinist epoch”—well, that’s “debatable” for Mr. Claeys, but his acknowledgment that there could even be a debate will be sacrilege to many of today’s Marxists. Stalin? Nothing to do with us, comrade.

“Marx and Marxism” is concerned more with Marx the thinker—a topic Mr. Claeys handles well, given the constraints of a shortish book—than Marx the man. (Those looking for a more conventionally biographical approach could do worse than opt for Francis Wheen’s “Karl Marx: A Life,” a shrewd, sympathetic and entertainingly Dickensian retelling from nearly 20 years ago.) Nevertheless, Mr. Claeys provides enough information to give a good summary of the story.

Marx was descended from a long line of rabbis on both sides; his father, Heinrich (né Hirschel) Marx, had converted to Lutheranism to avoid anti-Semitic restrictions limiting his ability to practice law. His son was, as Mr. Claeys relates it, a so-so student (other accounts are more complimentary). Not long after commencing his university studies, Marx switched from law to philosophy, a regrettable decision both for the world and for his finances.

Despite a happy marriage to an attractive and clever aristocrat—we’ll overlook the child he fathered with their long-serving housekeeper—Marx lived not so much hand to mouth, as hand to will, and hand to other people’s pockets, in particular those belonging to his wealthy cohort and collaborator, Friedrich Engels. An often desperately hardscrabble existence was made trickier still by Marx’s tendency to spend too much of the money he did obtain on less than proletarian niceties—or, more appropriately disreputably, on handouts to fellow revolutionaries, including on one occasion a substantial sum to fund the purchase of arms for discontented German workers in Brussels.

Mr. Claeys tracks both the development of Marx’s thought—a perennially dizzying work in progress—and the evolution of his career: early success as a radical journalist in Germany and France, involvement with new parties of the left, intermittent periods of exile or expulsion from this country or that. The Prussian authorities, increasingly alarmed by the revolutionary activity that had begun spreading across Europe in 1848, banished this troublemaker the following year. He settled in Britain, and London was to be his home for the rest of his life, a safe space from which he could plot, feud, politick and, despite being beset by procrastination and perfectionism, write and write and write, including “Das Kapital,” a pillow for Uncle Ho, perhaps, but a book that changed history.

Reading Mr. Claeys’s description of Marx the man—someone he evidently, if far from unconditionally, admires—it is both easy and reasonable to conclude that Marx’s personality set the tone for some of the most lethal strains in the regimes he inspired: “He was . . . almost totally unwilling to see anyone else’s viewpoint. The essence of democracy—compromise and the acceptance of opposition—was often beyond his capacity.” From his earliest years, Marx would tolerate very little dissent, and the sometimes lengthy, frequently inventive and sporadically repulsive abuse to which he subjected those with whom he disagreed (especially on the left) contain more than a hint of the prosecutors’ diatribes at show trials to come.

Marx died in 1883. Eleven people attended his funeral, but, as Mr. Claeys notes, “a year later . . . some 6,000 marched to the gravesite.” The cult was on the move. Something more than the cult of personality already emerging while he still lived, it came with echoes of earlier eruptions of millenarianism—a term that has long since expanded beyond its original theological definition to include, among other varieties of judgment day, the complete overthrow of society and its replacement with, in essence, heaven on earth. These similarities have been identified by scholars since at least the mid-20th century, but too often ignored.

Mr. Claeys, who is also a historian of Utopianism, is well equipped to avoid that omission. He acknowledges that millenarianism seeped into aspects of Marx’s philosophy, including both his view of history and his conveniently hazy vision of the communist paradise to come. This line of inquiry would have been worth pursuing further: Millenarianism is an ancient, proven formula that will find an audience as long as the credulous, the discontented, the jealous and the unfairly treated are among us—in other words, forever.

As monuments to cults go, another book, written from a perspective seemingly even further to the left than Mr. Claeys’s, the massive “A World to Win: The Life and Works of Karl Marx” would be hard to beat. The University of Gothenburg’s Sven-Eric Liedman “has been reading and writing about Karl Marx for over fifty years” and published this book in Swedish in 2015; it was released in America this year in a translation by Jeffrey N. Skinner.

Those searching for a truly detailed discussion of Marx (nearly three pages are dedicated to a letter young Karl wrote to his father in 1837) should turn here. Mr. Liedman has criticisms of Marx, but his overall opinion is—how to put this—enthusiastic: “No social theory is more dynamic than his.” Yet the fact that Mr. Liedman’s book is something of a shrine (“we need him for the present, and for the future”) isn’t all bad, from this reader’s point of view. A lucid, scholarly guide to an overelaborated, frequently opaque, often misguided but historically important set of ideas is of obvious value. And so is an erudite, closely reasoned defense of those ideas: An apostle can help explain a messiah.

Mr. Liedman’s reverence can, however, cloy: Marx’s “unwillingness to compromise of course had another side: the magnificence of the project.” While Marx undeniably possessed both an astonishing mind and—when he wanted—a brilliant prose style, Mr. Liedman overdoes the hosannas: “a festive pyrotechnic display of words,” “one of his very finest aphorisms,” “a remarkable brightness around these few lines,” to take but a few.

A characteristic of millenarian movements is that when their prophecy proves false, the failure tends to matter far less than it should. Marxism has proved no exception, but maybe with a touch more reason than most. For all his failed predictions, crackpot theories and rococo blind alleys, Marx was also very early to understand the ever-accelerating productivity unleashed by “bourgeois” capitalism as a truly relentless, unprecedentedly revolutionary force. But the consequences of this revolution would, he believed, eventually bring down its own creators. That cataclysm has been a long time coming, and, if it ever arrives, there will be a distinct twist to the script.

In their hunt for (Marxist) promise today, Messrs. Liedman and Claeys emphasize mainly contemporary income inequality. They should pay more attention to technology. As automation grinds through jobs, wages and up the social ladder, a landscape with some disturbing resemblances to that foretold by Marx is coming inexorably into view.