Chick-Tac-Toe

National Review, December 23, 2002

MOST people go to Las Vegas for the gambling. Dazzled by neon, crazed by greed and Wayne Newton, they challenge the odds, trying to outwit the trickster goddess, Lady Luck herself. But I was there for a different, wilier adversary. I was in town for the chicken. It was payback time, a chance for the revenge I'd seen waiting for since that shameful, sultry night in Manhattan's Chinatown all those years ago. You know the sort of evening—too much Tsingtao, not enough sense. Next thing, you're in a seedy airless room doing something you shouldn't: in my case, playing a chicken at tic-tac-toe—and losing. Years later I tried to track the bird down for a rematch, hut it had flown the coop: dead in a heat wave, said some, off hustling in another hutch, said others. And then the rumors began—whispers about tic-tac-toe-playing poultry spotted in Atlantic City, claims of sightings in Indiana and Las Vegas, reports of the theft of three uncannily smart birds from a county fair in Bensalem, Pa. And always there in the background, a muttered, mysterious name: Bunky Boger.

The stories are true. A slick chicken is back on the scene, hut this time it's not alone. Chickens skilled in tic-tac-toe have come home to roost in no fewer than three locales—all of them casinos (and two of them called Tropicana)-— while others, avian carny folk, work the county-fair circuit, usually without being stolen. The source of this scourge? Bunky Boger. Turns out he runs a Springdale, Ark., farm known for training animals to perform the feats some call remarkable and others just plain peculiar. Bunky's brainy brood docs not stop at the O's and the X's. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, these chickens dance and play basketball too.

NATIONAL REVIEW's budget for investigating strange tales from Arkansas has shrunk over the last couple of years, so I can't claim to have checked Boger's methods. There's talk, however, of "positive reinforcement" (basically the use of food as a reward) and other behaviorist techniques of the sort developed by the psychologist B. F. Skinner. Broadly speaking. Skinner saw personality as a blank slate, pliant and ripe for conditioning. This is an idea that played no small part in the disasters of 20th-century collectivism, but it seems to work well when applied to chickens. Far mightier than the Mighty Ducks, Boger's chickens are tricky to lick. Recorded defeats are few and hit between; just a handful this year, so rare that the two Tropicanas (Atlantic City and Las Vegas) are prepared to offer $10,000 to any customer able to take on the chicken, mano a claw, and win.

Ten thousand dollars? That's not chickenfeed. Maybe I was counting chickens before they were dispatched, but revenge, it seemed, was going to be profitable as well as sweet.

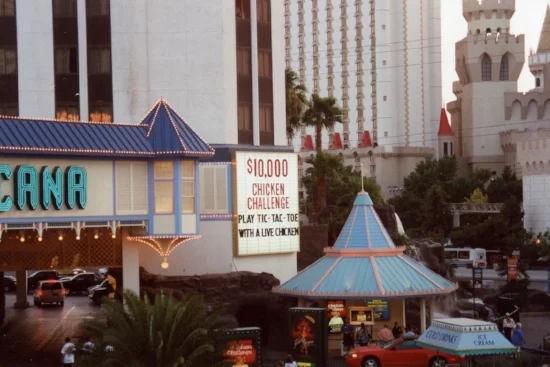

Outside the Las Vegas Tropicana, all is anticipation. Large signs proclaim the "Chicken Challenge—Play Tic-Tac-Toe With a Live Chicken." A poster shows a chicken contemplating a tic-tac-toe Götterdämmerung. The creature's blue eyes (contacts?) are bulging with tension. It's sweating pullets. Good.

Las Vegas, August 2002 © Andrew Stuttaford

Once you're inside, there is a brief detour for paperwork (tackling the chicken is free, but prospective foes of the fowl have to sign up beforehand for the casino's optimistically named "Winner's Club") and then it's on to the main event, first heralded by a glimpse of white feathers fluttering in a large, glass-fronted booth and an amazed Italian muttering, "Pollo? Un pollo?”

A crowd has gathered behind the velvet rope, would-be contestants (around 500 over a twelve-hour day) looking for- ward to the game, and, less admirably, spectators waiting to jeer. It's a tough arena. Be felled by the fowl, and the display attached to the booth will declare your shame for all to see with flashing lights and an announcement of the result ("Chicken wins"), followed by insulting slogans ("You're no egg-spert" is one of the milder examples). The crowd is no kinder. The losers slink off amid mocking laughter, crushed and beaten-—well, a little embarrassed anyway.

And then it's my turn. I step up to the booth, staring fiercely at the chicken. It's time for some psychological warfare. The creature gazes back imperturbably. Is that intelligence I see in those beady black eyes? Is it a brainy bird or merely bird-brained? Mr. Boger seems unable to decide. In a confusing interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, the Springdale Svengali boasted that his chickens were "smart little peckers" but then, in a disloyal twist (did a cock crow three times?), he went on to condemn them as "kind of simple-minded." "You wouldn't," he said, "want to take their advice on the stock market"—which, if New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer is to be believed, would put the chickens on a par with a number of Wall Street's leading investment banks.

Simple-minded or not, my chicken moves away from the glass window of her booth and heads at a leisurely pace into a more secluded area, a "thinking" booth within the booth. Suddenly the chicken makes its choice (the bird always gets to go first). An O appears on an illuminated touch screen, together with the information that I have 15 seconds to respond. And so I do. X. My opponent operates under no such time constraints. As the seconds drag by, the display flashes up the words "Chicken's thinking," this contest's equivalent of the annoying little hourglass that always accompanies those slower software moments. There are, of course, some skeptics, wild-eyed folk—Chicken Challenge's Capricorn One crowd. They whine that the bird is a fake, a feint, fowl play at its worst. The thinking booth, they claim, is nothing more than a device to hide the fact that the chicken does nothing—its "moves" are all the work of a pre-programmed computer. Is there a HAL in the henhouse, an updated twist on "The Turk," that supposedly chess-playing automaton once famous for puzzling 18th-century Europe.' I prefer not to think so.

The Tropicana, Las Vegas, August 2002 © Andrew Stuttaford

O, X, O. As the game progresses, it becomes clear that it's too soon for the chicken to crow. The hen tenses. At one point a move is preceded by a savage, primeval display. Wings beat, and that noble head turns towards me, cruel, merciless, and proud. It's a chilling moment. The chicken, like all birds, is descended from the dinosaur. Could the Tropicana be transformed into Jurassic Park?

Well, no. An O and an X or so later, and the game draws to its close. It's a tie. The chicken acknowledges the result with a curt nod and turns away, ready for the next challenger. I walk off, honor satisfied, but true revenge for the Chinatown fiasco remains elusive. Next stop, Atlantic City.

In conclusion, it's important to point out that, in keeping with NATIONAL REVIEW’s policy, no birds were harmed in the writing of this article. PETA, however, has complained about the Chicken Challenge, and a representative of the chicken activists at the Virginia-based United Poultry Concerns condemned the whole spectacle as "degrading" and "derisive." Judging by the Las Vegas setup, that seems harsh. The Chicken Challenge booth is relatively spacious and housed in an air-conditioned environment. There's food and water inside. What's more, according to a spokeswoman from the Tropicana, no one chicken has to play for more than about 90 minutes at a time. The booth is manned—if that's the word—by chickens drawn from a squad of 15 (all known as "Ginger"). Each Ginger is regularly rotated but never, apparently, rotisseried.

Bunky Boger himself seems untroubled by the controversy. As he explained to the Review-Journal; "A chicken would rather play tic-tac-toe than float around in a can with noodles."

Find me a chicken that could argue with that.