Democracy Dies in Regulators’ Offices: The SEC, Regulatory Creep, ESG, and ‘Climate’

This isn’t the first time that I have written about regulatory creep, and it won’t be the last. Lacking the legislative majorities required to push through much of his agenda, Joe Biden is turning to regulators for help. His won’t be the first White House to rely on unelected bureaucrats in this way, but one — how to put this — distinctive aspect of the Biden approach is the way that regulators are, with, presumably, the administration’s connivance, extending their mandates to places they were never intended to go. It’s not pretty, but as a device to bypass the democratic process it can be startlingly effective

Read MoreAs GameStop Stalls, Will Regulators Start?

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine continues to be a tremendous source of insight into the GameStop saga, but one possible response to what has happened, which is set out in one of his must-read articles on this stock’s excellent adventure/bogus journey (take your pick) and buried within the following not-to-be-taken-literally passage, should be treated with caution:

We have discussed before the sort of creaky U.S. rules around who can buy what sorts of risky investments, and I have proposed a simple standard. I call it the “Certificate of Dumb Investment.” Under this standard, anyone can buy diversified low-fee mutual funds to their heart’s content, but to buy dumb stuff—private placements but sure let’s say also volatile meme stocks—you have to go down to the local office of the Securities and Exchange Commission and sign a form saying that you know that what you’re doing is dumb, you know you will probably lose all your money, and you forfeit forever any right to complain. Then you can do whatever dumb thing you want.

Click on the link embedded in Levine’s text to see where he expands (in an article written in 2018) on how his Certificate of Dumb Investment regime would work. Some of this, I reckon (I cannot imagine why) contains just a touch, well, perhaps more than a touch, of hyperbole: “Then you take the form to an SEC employee, who slaps you hard across the face and says ‘really???’ And if you reply ‘yes really’ then she gives you the certificate.”

Read MoreRide of the Regulators

National Review, November 3, 2008

First fire, then brimstone, then collateralized debt obligations: Both Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega and Iran’s Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati (a hardliner’s hardliner) are arguing that the 2008 crash is down to the Big Fellow upstairs. Ortega reportedly maintains that the Almighty is using the chaos on Wall Street as a scourge to punish America for imposing flawed economic policies on developing countries. The ayatollah, meanwhile, insists that it is Uncle Sam’s unspecified “ugly doings” that have brought down the wrath of Allah, and with it the housing market. I’m not entirely convinced either way.

I am, however, sure that the crash is a godsend for regulators, meddlers, and big-government types of every description, nationality, and hypocrisy. Speaking on behalf of his famously clean administration, Russia’s president, Dmitri Medvedev, has called for stricter regulation of financial markets, as has the EU’s top bureaucrat (the mean-spirited might interject that the EU is about to have its accounts rejected by its auditors for the 14th consecutive year). They are joined by the green-eyeshade types at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and the always-understated Nicolas Sarkozy, who pronounced: “Laissez-faire is finished.” Sacre bleu!

Closer to depreciated home, Democratic congressman Barney Frank has blamed the crisis on a “lack of regulation,” a gap that he obviously plans to fill and more with the eager assistance of Nancy Pelosi. In the now-infamous speech she made ahead of the first, calamitous House vote on the bailout package, Pelosi claimed, ludicrously, that the source of our problems lay in the fact that there had been “no” regulation and “no” supervision. Even if we make necessary allowance for hyperbole, dishonesty, and ignorance, Speaker Pelosi’s revealing choice of adjective indicates that an extremely heavy-handed, destructive, and counter-productive regulatory regime lies ahead.

The ideological winds have shifted. With free markets generally, and Wall Street specifically, being blamed for an economic predicament that is grim and getting grimmer, it’s going to be a struggle for those of us on the right to convince the rest of the country that the solution is not a financial system micromanaged by the feds. Nevertheless, we must try.

It was too much to expect John McCain to contribute anything to this effort, and, with his diatribes against “greed and corruption” on Wall Street, he hasn’t. But if, to use a vintage insult, demonizing “banksters” is unhelpful (full disclosure: I work in the international equity markets, but I am writing here in a purely personal capacity), trying to pin the blame on the Democrats’ uncomfortably cozy relationship with Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae won’t do the trick either. It is true that this unlovely couple was running amok and that the Democrats helped them do so. But the conceit that the failure to regulate them appropriately is in itself an argument against wider financial regulation is absurd. Equally, to proclaim that free markets are always their own best regulator is not only to fly in the face of history and common sense but also to ensure that the debate will be lost.

As we survey an economic landscape littered with shattered 401(k)s, broken banks, and anxious businesses, the idea of leaving the free market to clean up after itself comes perilously close to the old notion that it was sometimes necessary to destroy a Vietnamese village in order to save it. The free market is a very powerful engine for economic growth, the best we have, but it is that power that makes it too dangerous to be left solely to its own devices. Adam Smith certainly understood as much. To face this reality is to recognize that the sensible debate is not whether financial markets should be regulated, but how much and in what manner.

As a starting point, we must accept (as if there could now be any reasonable doubt about it) that the interconnectedness and scale of today’s markets mean that far more institutions than had been previously thought are, as the cliche goes, “too big to fail.” (I’d add that this country’s fragmented regulatory structure has now clearly shown itself too small to succeed.) Market fundamentalists will hate it, but it’s time to be honest about this. Bear Stearns was too big to fail, but so, quite possibly, was Lehman Brothers. And if an institution is indeed too big to fail, that means it is effectively underwritten by the poor conscripted taxpayer. Under the circumstances, it’s neither unreasonable nor inconsistent with free-market principle to insist that the price of that privilege (which can bring with it a competitive advantage) be a more cautious approach to risk. Not to do so would, in fact, provide a perverse incentive to do the opposite, creating the notorious “moral hazard” about which we read so much these days.

Now that they have become conventional banking companies, this more closely supervised world is where Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs will, justifiably, find themselves. The question, then, is which other institutions should be brought within a tighter regulatory net. The answer is, I suspect, to be deduced from facts of size, function, and client base, but it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the category of “too big to fail” will include at least some money-market funds and — remembering the Long-Term Capital Management fiasco — perhaps others on the buy side.

Getting this right is crucial because the corollary is that we will then know which firms are not too big to fail, and can ensure they are allowed to carry on business with minimal government interference. Traditionally, establishing a sleep-at-night risk profile has been a matter of closer regulatory scrutiny and ever-tougher capital requirements, but in the wake of this trauma we must ask whether certain instruments are simply too complex, too leveraged, and too thinly traded to be permitted anywhere near a “too big to fail” balance sheet. I may not share Warren Buffett’s politics, but it’s impossible to deny that his 2003 warning about the dangers of derivatives (“financial weapons of mass destruction”) was, to say the least, prescient.

Yes, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange is establishing a facility for the centralized trading and, critically, clearing of credit-default swaps (on some estimates a $58 trillion market, although that number may be swollen by double counting), something that, if successful, should enhance both liquidity and pricing transparency. Additionally, attempts are being made to come up with a mark-to-market rule that accurately reflects risk without triggering unnecessary disaster (although it is essential that any such change be accompanied by greater disclosure of “off balance sheet” exposure). The role of the ratings agencies is also being subjected to long-overdue reappraisal. These are all steps in the right direction, but they are no panacea. For a different approach, go to Spain. The Spanish central bank discouraged the banks it supervised from participating in the structured-credit markets. This had the virtue of simplicity and, it seems, some degree of success. It’s not a perfect precedent (some of these banks were playing around with structured-credit products), but it is a start.

Even though Spanish banks largely kept clear of America’s subprime swamp, they could not escape their own. Spain too had a real-estate bubble. Manias, like panics, are global. But we do learn from them. The Bank of Spain’s relatively tough line has its origin in a major Spanish banking crisis some three decades ago. America’s real-estate lenders are unlikely to repeat the mistakes they have made (at least on the same scale) for many years: burned fingers and all that. Lending standards have tightened and will probably stay tight for a long time. This is not to suggest that the regulation of housing finance should be left untouched. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, George Soros (I know, I know) has argued that we should look at the Danish mortgage-bond market for inspiration, and there’s something to that. There’s no space here to go into the details, but suffice it to say that the Danish system aligns, prices, and manages risk far more effectively than anything we have in the United States. It would be nice to report that, as a result, the descendants of Polonius (“Neither a borrower nor a lender be”) had avoided gambling on Danish real estate. Unfortunately, they didn’t. To speculate is human.

But the housing crisis is also a cautionary tale of political mismanagement (or it would be if anyone were paying attention). While promoting a home-ownership society is a legitimate function of government (thus the tax deductibility of mortgage interest should be retained), it must be exercised openly and honestly — and it must be properly costed. The misuse of the Community Reinvestment Act and, even more, the odd, anomalous, and unhealthy existence of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (they should be broken up and privatized as soon as possible, which in current conditions may be a while) played malign parts in this whole miserable saga. They are a reminder that excess, overreach, and worse can be as much a feature of the public sector as of the private. Preventing such abuses in the coming age of regulatory fervor will be the next challenge.

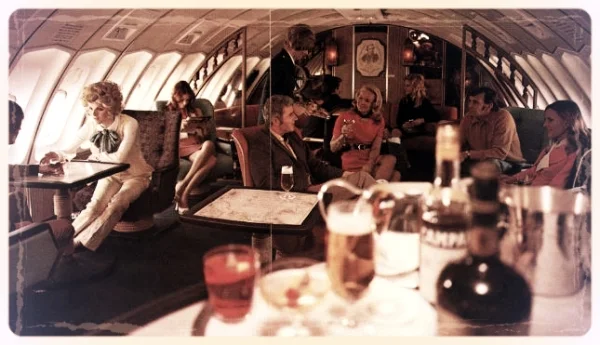

Spirits in the Sky

National Review Online, July 24, 2001

Is it possible, do you think, that Democratic senators are, in reality, demons sent by the Devil to pester, humiliate, and torment the rest of us? It may be a somewhat far-fetched theory, but take a look at the latest proposed policy initiative from Dianne Feinstein and see if you can come up with any other explanation.

Ms. Feinstein, the senior senator from California, has decided that the experience of air travel in this country needs to be made worse. The senator, a lawmaker with, clearly, too little to occupy her time, has recently written to the CEOs of seven major air carriers suggesting that they should not serve any passenger more than two alcoholic drinks in the course of a domestic flight.

Now, a "suggestion" from Dianne Feinstein is, like a "request" from Don Corleone, something to take seriously. Just in case any of the CEOs did not understand this, the sober-sided senator spelled out the threat implicit in her proposal. If the airlines would not comply "voluntarily" they would be required to do so by law. "I am," she warned sternly, "in the process of writing legislation." And that legislation would be tough. The ban, she explained, would apply "regardless of the type of alcoholic beverage served."

Let us imagine what that could mean. You are in Coach, in a middle seat narrower than George W. Bush's Florida majority. One neighbor, grotesquely obese, is spreading out from the confines of his chair into your own space. The other, who does not appear to have washed for some days, is sobbing quietly after a nasty spot of turbulence over Des Moines. Two rows behind, a baby screams, but undeterred his mother carries on with the grim task of changing a diaper then and there (she has little choice — the line for the restroom stretches halfway down the plane). The flight itself, theoretically a six-hour hike from New York to Seattle, took off very late owing to unspecified "trouble" at O'Hare. You will, you already know, miss the meeting that was the purpose of your journey in the first place. The flight attendant has just informed you that the last chicken entrée has already been taken, leaving a choice of a bean-based mush or a packet of honey-coated pretzels. It has been two or three hours since your last drink. To numb the pain, you ask for a third Bud Light. Under the terms of the Feinstein fatwa your request will be denied.

If there is anything guaranteed to spark an outburst of anger, this is it, which is ironic really, as the alleged purpose of the two drinks limit is to reduce "air rage." Of course, why Sen. Feinstein should be so worried by this subject is not clear. The senator was, after all, famously relaxed ("we've got to step back…let cooler minds prevail") when, in this year's most spectacular instance of aerial misbehavior, a hot-dogging Chinese jet collided into an American surveillance plane. We can only speculate as to what it is that has now led Ms. Feinstein to take a new harder line against trouble in the sky. It would, of course, be absolutely inappropriate to suggest that a double standard is at work and quite, quite wrong to hint that the senior senator from California is a self-important busybody, who finds it easier to boss around American citizens than stand up to Communist China.

No, the answer must lie elsewhere. Was there, perhaps, an incident, senator, a squabble, maybe, on one fraught flight over just whose suitcase was going to have priority in a jam-packed overhead locker? We can only speculate. There is no evidence of such a drama, but then, why worry too much about that? There is no evidence of any epidemic of air rage either, but that does not seem to have stopped Ms. Feinstein.

The real data are, in fact, rather reassuring. In response to the senator's proposal, a spokesman for an airline industry group, the Air Transport Association, has claimed that most of the four thousand or so (usually fairly minor) incidents of "air rage" that take place each year do so on the ground. Minor or not, that is four thousand too many, but it is worth remembering that U.S. airports catered for over six hundred million passengers last year. Based on those statistics, therefore, unruly travelers account for .0007 percent of the total, and most of those are enraged not by drink, but by delays. One of the principal causes of those delays, Sen. Feinstein, has been Washington's failure to bring the private sector into the management of the air-traffic-control system.

What is more, when a drunken passenger is, or may become, a problem, the airlines already have all the powers they need. As Ms. Feinstein's own press release admits, under FAA regulations airlines are prohibited from serving alcoholic beverages to any person aboard who appears to be intoxicated. Disorderly passengers can be handcuffed or otherwise restrained. Quite rightly, as a number of loutish holidaymakers have recently discovered, they can also be prosecuted.

As for those who argue that two drinks should be enough for anyone, well, that may be true for them (and for me. I'm a very frequent flier, but, in the air at least, a very infrequent drinker) but it is not for others, and those folks should be left to make their own choices. A drink or three can help wile away the time, or soothe, perhaps, the truculent traveler who might otherwise cause just the sort of problems which, supposedly, so alarm the senator. In addition, most of us know those terrified fliers (hi, Mom!) who need more than a little something to help them through their ordeal. Why should they suffer?

In the end though, the utilitarian case misses the point. This particular example, the right to that third beer, may be not be the most important cause, but what matters here is the underlying principle, the principle that government should not take away any of our freedoms without a good reason. In this instance, Sen. Feinstein has not shown us that reason. The facts do not support her argument, and if we reject Satan as an explanation for Dianne's draft diktat (and, probably we must, although the Devil does, notoriously, find work for idle hands), then the only motive that can be found is in her own mindset, one all too typical of her party's leadership: priggish, arrogant, condescending, and unbelievably interfering.

And you don't need to get in an airplane to be angry over that.