Fighting for a Lonely Planet

I am Legend

The New York Sun, December 13, 2007

Hell may not, whatever Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote, be "other people," but other people, or what's left of them, certainly conspire to mess up the second half of "I Am Legend," a movie that was, until then, developing into one of the finest science fiction movies of recent years.

In his retelling of Richard Matheson's harsh, hallucinatory novel from 1954, director Francis Lawrence is brilliantly successful in re-creating the book's post-apocalyptic vision of a survivor hanging on to life, and the remnants of civilization, in a city that is intact — but not — and where he is alone — but not. It's an extraordinarily compelling idea, and given the relish with which Homo sapiens, that most narcissistic of species, savors the spectacle of its own destruction, it's no great surprise that this is the third movie, after "The Last Man on Earth" (1964) and "The Omega Man" (1971), based on Mr. Matheson's story. However, in the bleak grandeur of its images at least, this latest version is easily the best.

The Brooklyn Bridge is a ruin. Times Square more unkempt even than in the days before Mayor Giuliani. Deer roam through Midtown. We see Manhattan, both Eden and Pompeii, slowly, remorselessly, and with only the occasional cliché (the errant lion last seen in "Twelve Monkeys" makes an appearance) revert to wilderness. But, however beautifully crafted (and in this movie they are), tracking shots of a verdant, abandoned city are not, in themselves, enough to convey the true sense of catastrophe. For that you need a witness: Charlton Heston, say, raging at the sight of the Statue of Liberty toppled, broken, and half-buried in the sands of a planet that now belongs to the apes.

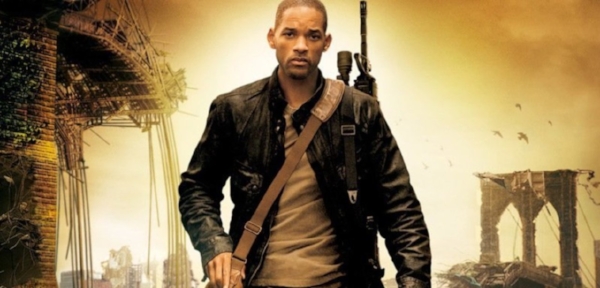

In "The Omega Man," the tireless Mr. Heston, harbinger of global doom, was again that witness. But neither his performance, nor that of the no less grandiloquent Vincent Price as the Last Man on Earth before him, can compare with what Will Smith brings to "I Am Legend" as Robert Neville, Mr. Matheson's bereft and resourceful hero. By definition, this is for long stretches a solo role, and thus not easy to do, but with little more than his dog for support, Mr. Smith skillfully conveys the loneliness, determination, and increasing mental strain of life as a Robinson Crusoe marooned on the island that was once his home, but is now, well, something else.

In part, Neville has adapted by turning Manhattan into his private playground (taking golf swings from the deck of the USS Intrepid, gunning a muscle car down empty avenues), but it's a playground where the pleasures are as transient as they are solitary. What really keeps him going are the routines — obsessive, meticulous, and tough — of the work he carries out while hunkered down in a bunkered-up brownstone on Washington Square. Neville is a military virologist (the novel's Neville is, by contrast, an everyman, which makes his plight as the last man all the more affecting), and he is still, even now, trying to find a cure for the man-made plague that took his world away.

He has to, because the virus didn't finish off everyone else. In Mr. Matheson's book, a number of those infected are transformed into vampires. In Mr. Lawrence's take, these lethal unfortunates are reduced to "dark seekers," feral, albino, debased ex-men who look as if they have escaped from the set of 2005's "The Descent," but behave with the hyperkinetic ferocity of the zombies in "28 Days Later" (a fair enough exchange, one might think: The latter film owed a considerable, and insufficiently acknowledged, debt to Mr. Matheson's tale).

That makes for some undeniably exciting scenes of chase and combat, roaring and head butting, but the decision to dumb the infected down drains much of the intelligence and the horror from the original concept. Once we understand the nature of the threat that the dark seekers represent, the distinctiveness of this movie begins to evaporate. It's still highly entertaining ("I Am Legend will, I reckon, be a massive hit, and deservedly so), but its early promise is frittered away.

The tumble gathers pace after the arrival of two other (healthy) survivors — a young woman (Alice Braga) and a child (Charlie Tahan). Helpfully enough, they extricate Neville from a tricky encounter with some dark seekers, but their key function is to drag the film even further away from the pitiless premise underpinning the novel that inspired it. Indeed, they are used to inject a spiritual, even religious, dimension into a narrative that, as first conceived, had none, and needed none.

If it's not absurd to suggest this about a work involving vampires, Mr. Matheson's book is best seen as a classic of mid-20th-century realism, unflinching in its acceptance of impermanence, chance, and an uncaring universe. We live now in dreamier, less clear-eyed times, and Mr. Lawrence has tailored his movie accordingly. You'll have to see for yourself how it ends, but I will say that it recounts a legend that bears little resemblance to that of Mr. Matheson's original Neville, the man whose destiny was to become a legend of a far darker kind, "a new terror born in death, a new superstition entering the unassailable fortress of forever." To understand how, and why, read the book. Oh yes, see the movie too. It's good, but it should have been — could have been — great.