Stupid Pet Tricks

National Review Online, September 30, 2003

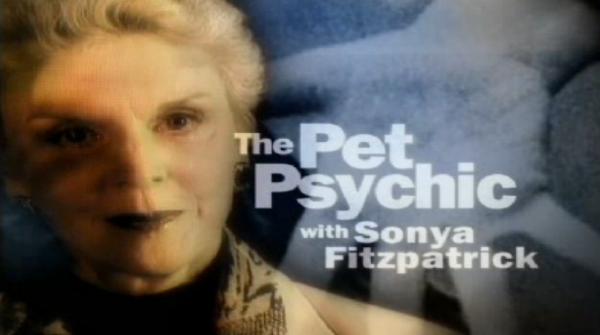

Even at the best of times there is something about a monkey that mocks our delusions of grandeur, and this was not exactly the best of times. The monkey, burdened with the name of "ET" and the undignified habit of chewing his tail, looked first irritated, then puzzled, then sarcastic, and then, quite frankly, appalled, as a striking sixtysomething Englishwoman peered intently into his cage, called him "sweetie pie," claimed to read his mind, mentioned some personal matters that ET would rather not have had aired on national television and then smothered his hands with kisses. Poor ET had just survived a close encounter with Sonya Fitzpatrick, America's most famous pet psychic. As for Sonya, she knew what was wrong. How could she not? ET had told her. There was a parasite under that much-chewed tail (pointing at, her, well, tailbone, Sonya explained that she could feel the parasite's energy — and the itching — here) that the vet had somehow missed. Her solution? Very dilute, it turned out. Something homeopathic would do the trick, but there was, Sonya warned, another problem. ET was missing his pal. Amazed, ET's keeper explained that the luckless primate had been picked on by most of the other monkeys ("he thinks they are extremely rude," interrupted Sonya sympathetically), and so had been moved to separate quarters. She did, however, remember that ET had got on rather better with one monkey, the accurately but unimaginatively named, Buddy. Sonya's remedy once again came in very small doses — from time to time Buddy should be allowed to come over to visit. Case closed!

And that's how it usually goes on The Pet Psychic, Sonya's TV show, 45 minutes of critter clairvoyance, menagerie miracles, and fauna trauma that stand out as some of the more intriguing viewing on the Animal Planet channel, no mean feat against competition such as Amazing Animal Videos, Animal Cops, Animal Precinct, Emergency Vets, Pet Story, Pet Star, Judge Wapner's Animal Court, and Total Zoo. The Pet Psychic is weirdly compelling watching, a chance to gape at poor dumb creatures and the odd bond they form with Sonya. I'm referring, of course, to the humans that agree to appear on the show alongside their pets, weeping, sniffling, shyly laughing, or revealing too much of their lives — they make a spectacle far more entertaining than anything that our four-legged friends could ever provide.

There's Lisette, for example, flirty in her apartment as she confessed the details of a love life that has, Sonya concludes, thrown her marmoset, Peyton, into jealous turmoil (Peyton fancied Lisette's ex) or the strain on Dawn's face when she revealed that the relationship between her husband and "her soul mate" (Boogie the show horse) had degenerated into outright violence — Boogie had bitten the poor man's backside — leaving Dawn to worry that (to quote the Animal Planet website) that "his actions could prevent him [the horse, not the husband] from performing."

Sometimes, there are life-and-death decisions to be made. "There's something with the bladder," suggests the great psychic, nattily shod in her trademark riding boots and staring intently at Kramer the dog. Indeed there was. Kramer looked humiliated, but embarrassment was the least of his problems. There had been talk that it was time to put this pooch to sleep. Everyone began to sob, while Kramer lay flat on the floor doing his best to imitate a canine corpse.

In the event, Sonya prescribed understanding rather than the needle, but even if the verdict had gone the other way, Kramer would have had nothing to fear. To Sonya, animals aren't dumb even when they are dead. As she explains in her book, What the Animals Tell Me, "animals are spiritual beings. When they die, they do not go off into a void...they go to a place of unearthly beauty [after swimming through "healing waters"], where joy, peace and happiness reign supreme; where memories of pain, care and worries fade into bliss." Later, after, presumably, consulting the angels that await them on that "golden shore," they may choose to reincarnate or, perhaps, just come calling, "understand that they have not left us; they are still with us and they visit us in their energy bodies." One way or another, Kramer will be back.

This may be dodgy theology, but it makes for a happy ending, and a cheerful — if usually tearful — conclusion to the segment of the show dedicated to pets that have "passed into spirit." The messages from the other side are usually upbeat and reassuring. Kerry the spaniel was grateful ("thank you, thank you") for the fact that he was put to sleep, and there was "a tremendous amount of love" coming from Sasha, a sub-Scooby Great Dane, who was "very happy in the spirit world" and quite understood that Maria, her "mum," did not have, ahem, quite enough time for her in her final illness.

Don't worry: The show doesn't only feature conversation with pets that have petered out. As we've seen from the cases of Peyton and Boogie, Sonya, a blend of Dr. Doolittle and Dr. Strange, claims to talk to living animals as well as dead, thanks to her innate telepathic skills (Good news: We all have them!), brought out in her case by profound childhood deafness. As animals, she says, communicate telepathically (Forget Mister Ed or garrulous, unsubtle mynah birds), it was no surprise that they became young Sonya's closest friends. Sadly, a bloody incident involving geese, her father, and Christmas lunch led her to force "a door shut in [her] mind for what [she] thought would be forever."

The door opened again over 40 years later in, rather surprisingly, Houston, with the appearance of first an angel ("large wings...beautiful and gentle face") and then St. Francis, both of who told Sonya that she was going to be working to help animals. It was God's work. And who's going to argue with Him? Not Sonya. She put two and two together and made a TV show, a writing career, and, at a reported $300 per hour, a consultancy business out of her long dormant skills, telepathic or otherwise.

Sonya has plenty of satisfied customers. According to the Animal Planet website she has "helped more than 3,000 clients worldwide in many capacities — to achieve a better understanding of their pets, to solve behavioral problems, and to cure their animal friends of physical ailments." Her show is filled with guests who are astonished by her insights. How did she know that Bill the cat liked to play with a "round thing"?

Hmmm, I grew up with one Clumber spaniel, two unfortunate hamsters, and a budgerigar. Excluding, perhaps, the moment that the budgie was killed by the dog, they were all a remarkably uncommunicative lot, so, on the assumption that the whole thing isn't rigged, my best guess is that Sonya is guessing. Viewers aren't told how The Pet Psychic is edited. The hits are shown, but not, I suspect, the misses. As for those hits, well, Sonya is a highly intuitive woman and thus, despite the occasional odd coincidence, they are probably the product of either luck, carefully vague language, or skilful "cold reading," the old carny technique of questioning the subject (or on this show the subject's "human companion") in a way that throws up the clues needed to come up with some miraculous "insight." TV's John Edward (a well-known human psychic) almost certainly uses the same trick, and it is no surprise to discover that he (and his dogs) have been on Sonya's show for a "meeting of minds."

Most important of all, Sonya benefits from people's willingness to believe in what she has to peddle. There's nothing startling about this. We live in an age where superstition seems set to scupper skepticism. Society's reluctance to assert that anything is false — a product of postmodernism, politeness, and, ironically, the decline of some of the more established churches — has left us prepared to accept that just about any old nonsense could be true, the more exotic the better, particularly when it comes clothed in vaguely "spiritual" dress and builds on the existing beliefs of the more credulous among us.

Sonya's angels and the chatter from beyond the pet cemetery are tailor-made for such an audience, while, like any savvy modern spiritualist, Sonya throws in just enough "scientific" language (all that talk of "energy," and even Einstein rates a mention) for her fans to be able to comfort themselves — falsely — that their regression to the pre-modern is not yet complete. Besides, telepathy is practically a mainstream science in a time of alien abductions, healing crystals, and the Kyoto treaty. Only the most pedantic will want to challenge Ms. Fitzpatrick's claim that a telephone call with a pet's owner may be all that she needs to make that crucial connection.

There will be very few such challenges, for Sonya tells people what they want to hear. Her practical advice on animal care is benign and — once back in the material world — generally pretty sensible. The rest of what she has to say, normally delivered against a backdrop of the sort of soothing, simpering piano music more usually heard in a New Age bookstore, is deeply reassuring for anyone who can't be bothered to think too hard. It's a fashionably humble philosophy (we can learn so much from the simple wisdom of the animal kingdom), but conveniently egocentric, too: Not only do we have hidden powers (it's the telepathy, stupid), but in return for a little kindness (or, in the case of Sasha, benign neglect) our cats, dogs, iguanas, and parrots will love us now, and for all eternity. It's also attractively optimistic. We all get to Heaven. We don't really die. Our pets don't really die.

And even this show is probably good for nine lives.