I'm not altogether sure that New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art is taking its new, entertaining, and utterly charming exhibition dedicated to photography and the occult, entirely seriously. At the launch party for "The Perfect Medium" last month, giggling guests sipped smoke-shrouded potions to woo-woo-woo Theremin tunes, as vast projected images of the séances of a century ago shimmered silver-and-gray against the walls of a great hall that could just, just for a moment, have been in Transylvania. Up beyond the sweep of the Met's Norma Desmond staircase, a cheery crowd thronged past antique photographs of spirits, charlatans, and strange, vaguely unsettling, effluvia. As I peered closely, and myopically, at a mess of tweed and ectoplasm, there was a sudden, startling "boo" in my ear, and a pretty girl who had crept up behind me ran off laughing. As I said, unsettling. As I said, charming.

Unfortunately, the exhibition's catalog is, as such volumes have to be, straight-faced, straight-laced, and saturated in the oddball orthodoxies of the contemporary intelligentsia. With truth, these days, relative, and all opinions valid, it would be too much to expect an establishment such as the Met to say boo to a ghost and it doesn't. In the catalog's foreword the museum's director admits that "controversies over the existence of occult forces cannot be discounted," but he is quick to stress how "the approach of this exhibition is resolutely historical. The curators present the photographs on their own terms, without authoritative comment on their veracity."

Fair, if cowardly, enough, but a chapter entitled "Photography and The Occult" sinks into po-mo ooze: "The traditional question of whether or not to believe in the occult will be set aside...the authors' [Pierre Apraxine and Sophie Schmit] position is precisely that of having no position, or, at least not in so Manichean a form...To transpose such Manicheanism to photography would inevitably mean falling into the rhetoric of proof, or truth or lies, which has been largely discredited in the arena of photography discourse today," something, quite frankly, which does not reflect well on the arena of photography discourse today. Still, if you want a nice snapshot of how postmodernism can be the handmaiden of superstition, there it is. Standing up for evidence, logic and reason is somehow "Manichean", no more valid than the witless embrace of conjuring tricks, disembodied voices and things that go bump in the night. It's a world, um "arena," where proof and truth are reduced to "rhetoric," and, thus, are no more than a debating device stripped of any real meaning.

Thankfully the exhibition, principally dedicated to photographs of the spooky from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is itself free of such idiocies. The images are indeed allowed to stand "on their own terms" and, on their own terms, they fall straight down. They are, quite obviously bogus, balderdash, and baloney, slices of sepia stupidity that are magnificent proof of our species' wonderful curiosity and embarrassing evidence of its hopeless credulity. They were also very much the creations of their own time. After over a century of manipulated images, vanishing commissars and Hollywood magic, we are better at understanding that photography's depiction of reality can often be no more reliable than a half-heard rumor or a whispered campfire tale. One hundred forty years or so ago, we were more trusting in technology, more prepared to believe that the camera could not lie.

And we were wrong to do so. On even a moment's inspection the Met's ghosts, sprites, emanations, and fairies are as ramshackle as they are ridiculous, but all too often they did the trick. The work of the depressingly influential William Mumler, an American photographer operating in the 1860s and 1870s, may include a spectral Abraham Lincoln with his hands resting on the shoulders of Mumler's most famous client, the bereft and crazy Mary Todd Lincoln, but, like the rest of his eerie oeuvre, this insult to John Wilkes Booth was based on crude double exposure (or a variant thereof). Nevertheless, the career of the phantoms' paparazzo flourished for a decade or so, even surviving a trial for fraud (he was acquitted).

Or take a look at the once famous photographs of the Cottingley fairies (1917-20), absurd pictures of wee fey folk frolicking with some schoolgirls in England's Yorkshire countryside. Once you have stopped laughing, ask yourself just why, exactly, the fairies resemble illustrations from magazines. Well, it's elementary, my dear Watson, that's what they were (one of the girls finally confessed in 1981), but to the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a man who dedicated an entire book (The Coming of The Fairies) to the topic, and to many other believers, these fraudulent fairies were the real, fluttering, deal. Fairies were, explained Conan Doyle, a butterfly/human mix, a technically awkward combination that even the great Holmes might have found to be a three-pipe problem.

To be fair, by the 1920s, the possibilities of photographic fakery were no secret to the informed, but this made no difference to Sir Arthur, a convinced spiritualist who was to receive his reward by returning, like Holmes, from the dead (within six hours of his death, the author had popped up in England, moving on later to Vancouver, Paris, New York, Milan and, as ectoplasm, in Winnipeg). Conan Doyle believed what he wanted to believe, and so did his fellow-believers. Photographs could confirm them in their faith, but never overthrow it.

That's a recurrent theme of this exhibition. Yes, back then people were more inclined to give photographs the benefit of the doubt, but again and again we are shown pictures that were demonstrated at the time to be fake, something that did remarkably little to shake the conviction of many spiritualists that the dear departed were just a snapshot away. Even the obvious crudities and photographic inconsistencies could be, and were, explained as a deliberate device of the spirits—apparently they wanted to appear as cut-outs, illustrations, and blurs.

And it wasn't only photographers who egged the susceptible on. The idea that some gifted individual can act as an intermediary between the living and the dead is an idea as old as imbecility, but, after the dramatic appearance of New York State's rapping and tapping Fox sisters in the 1840s, the Victorian era saw a flowering of mediums, only too ready to impress the credulous with mumbo jumbo, materializations, mutterings, Native-American spirit guides (some things never change), transfigurations, grimaces, and tidings from beyond. Some were in it for the money, others for the attention, and a few, poor souls, may have actually believed in what they were doing.

The Met's show includes a fine selection dedicated to those mediums at work. Tables soar, chairs take flight, men in old-fashioned suits levitate, apparitions appear, and ghostly light flashes between outstretched hands. Most striking of all are the visions of ectoplasm snaking out of mouths, nostrils, and other orifices quite unmentionable on a respectable website. These grubby pieces of cotton, giblets, and who knows what were a messy but logical development, manufactured miracles for what was, in essence, a manufactured religion. Like the photographs, like dead Walter's mysterious thumbprint (don't ask), they were evidence. The immaterial had been made material, and in a supposedly more skeptical age, that's what counted. In great part, the enormous popularity of spiritualism in the later 19th century was a response to the threat that science increasingly represented to the certainties of traditional belief. Science had made Doubting Thomases of many, but spiritualism, by purportedly offering definitive proof of an afterlife, enabled its followers to reconcile ancestral faith and eternal superstitions with, they thought, fashionable modernity and the rigors of scientific analysis.

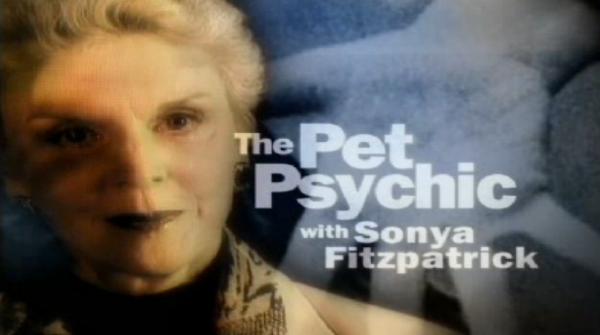

That the science was junk, and the evidence bunk, did not, in the end, matter very much. What counted was that old superstitions had been given a new veneer, and, if that veneer soon warped into a bizarre creed all its own, that's something that ought not to surprise anyone familiar with the nonsense in which mankind has long been prepared to believe—and still is. Any visitor to "The Perfect Medium" tempted to feel superior to the credulous old fogies now making fools of themselves on the walls of the Met should take another look at the metaphysical shambles that surrounds him in our modern America of snake churches, suburban shamans, mainstreet psychics, psychic detectives, pet psychics, psychic hotlines, spirit guides, movie-star scientology, alien abductions, celebrity Kabbalah, Crossing Over, Ghost Hunters, Shirley Maclaine, resentful Wiccans, preachy pagans, and (though I know this won’t be entirely welcome) don't even get me started on Intelligent Design.

Oh yes, "Happy Halloween," one and all...