Mean Girl

National Review Online, May 25, 2007

It was Friday night in New York City. I’d already drunk a couple of beers, so now was a good time for a quick rummage around inside Paris Hilton. I wasn't the first to do so, no, not even that evening, but what the hell? She didn't mind. Her eyes were closed, her face angular and serene, her back arched in almost Mannerist contortion, and her legs, ah her legs; they were akimbo, long, smooth, and inviting. I did, however, take the precaution of putting on a pair of slightly grubby white gloves before, well...

Well, since you ask, before carefully removing Ms. Hilton’s small intestine and toying, toying most gingerly, with her uterus.

I should explain. This wasn’t the real Paris, and shame, shame on any of you who thought otherwise. This was a facsimile, a rendering, or, more accurately, a tableau mort, showing her corpse, bare but for a tiara, cold, dead hands still clinging to cell-phone and martini glass. And as if this was not already enough to bring cheer to the stoniest of souls, the ensemble was completed by a forlorn Tinkerbell, the lap-dog and diarist, tiara-capped head (yes, hers too) a portrait of pathos, as she pranced and danced by the body of her fallen mistress.

According to the management of Capla Kesting Fine Art, the Williamsburg, Brooklyn, gallery where the ruins of Paris are now on display, the whole spectacle is an “interactive Public Service Announcement… designed to warn teenagers of the hazards of underage drinking.” Interactive? Yup, those teenagers-at-risk can perform an “autopsy” on the heiress or, at least, monkey around with her innards. The purported, and that’s the word, purpose is to give these youngsters “an empathetic view of drunk driving tragedy from the coroner’s perspective.” Scared straight, that sort of thing. This autopsy, lacking any hint of dignity, respect, or decorum (trust me on this), symbolizes the final destination of the DUI driver, and was, it is claimed, designed to strip away any hint of cool from Paris’s hard-partying ways. If you believe that, I have a collection of Hilton-designed pet wear to sell you.

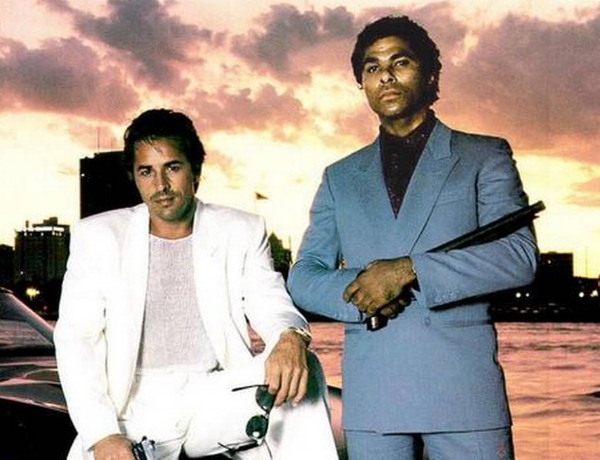

Always quick to check out an empress’ new clothes, the Fug Girls, the Cagney and Lacey of the Internet’s fashion police, were among the first to point out that if this sculpture was meant to highlight how drunk-driving can really mess a gal up, it might be a touch counterproductive. “Paris herself,” they explained,”would probably take one look at the installation and drawl, "Dude, I look great. DUI death is hot." They have a point.

The man behind the autopsy, Daniel Edwards, was in the gallery that Friday evening. Surrounded by the goatees, cropped hair, and black tees of a typical Williamsburg soiree, he was a genial figure, beaming, and gleaming in the finest white suit/beard/long mane combo to be unleashed on the planet since that day John Lennon strode out across Abbey Road. I asked him just how serious he really was about his, uh, message. If I were a ruthless undercover reporter, I’d tell you what he replied. But I’m not (we were just having a nice chat), and I won’t. Let’s just say that the likeable Edwards is a man with a sly sense of humor.

Those wishing to understand what Edwards is trying to achieve should look instead at his recent oeuvre. It mumbles for itself. True, the sculptor’s (sadly premature) deathbed portrait of Fidel Castro was something of a misstep, but a casting of “Suri Cruise’s poop,” a bust of a highly eroticized Hillary Rodham Clinton and, perhaps most famously, a statue of Britney Spears giving birth, not to mention that Hilton cadaver, all suggest a master prankster at work.

It’s an impression that is only reinforced by the press releases that accompany the unveiling of each project. Pompous, humorless, and as self-satisfied as they are self-important, they come across as pitch-perfect satires of the stifling piety of the scolds, nags, and busybodies now tormenting this once free country. If dead Paris can be a “warning” of the dangers of DUI (and, yes, yes, before mad MADD e-mail me with angry reproaches, I know that drunk driving is a bad thing), then Edwards’s Britney is no less plausible as a monument to the singer’s decision (as it then appeared) to put motherhood ahead of career.

Frankly, Edwards should charge admission. A buck’s a buck, Dan, and it would add a little more Barnum & Bailey to installations designed, I reckon, to be a part of the celebrity circus they simultaneously critique. Or something.

Still, it’s impossible not to be struck by the macabre coincidence that the Williamsburg autopsy is not the only image of a dead or dying Hilton out there in the marketplace. On the same day that Paris’s guts were opened up for inspection in Brooklyn, Californians were given the chance to take a peek at a “poignant” and “relevant” depiction of the poor girl’s suicide. A press release from the Venice Contemporary Gallery gave the details:

Artist Jason Maynard’s sculpture, entitled "SuicideSocialite," is the final piece in his 10-year exploration of the cultural relevance and symbolic reference to candy. The sculpture of Paris Hilton depicts the heiress sprawled out on a chez lounge with her wrists slit and candy spewing out of her veins…the piece takes on the guise of neither the moral high ground, nor the role of a public service announcement. In reality, this sculpture speaks more of Maynard's masterful portrayal of the pinnacle of modern day mob mentality's ability to build higher and higher pedestals for their celebrity objects to sit - for the pleasure of seeing them fall.

If we ignore the tortured prose, questionable spelling (chez lounge?), and the candy, there’s no doubt that Maynard has a point. Whenever a celebrity stumbles, there’s a crowd out there ready to peer, to leer, and to cheer. That’s particularly true when that pratfallen celebrity is Paris Hilton. She may not be the nicest of people, and she has certainly brought her current legal troubles upon herself, but, after witnessing the rejoicing, the vitriol, and the sermonizing that swirl around her eagerly anticipated imprisonment, I’ll admit to feeling a twinge of sympathy for the inmate-in-waiting. Libertarian blogger Lew Rockwell went a little far when appearing (vaguely) to compare Hilton’s coming Calvary with that of Christ’s, but his thinking was as least charitable. The same cannot be said of all those who seem to have forgotten that the star of One Night in Paris ranks rather low in the evildoer hierarchy, a Martha Stewart more than a Madame Mao.

And incarceration alone is not punishment enough to satisfy the baying, self-righteous mob, sweaty, and prurient, that has surged from couch, blog, suburb, and trailer park to demand what it sees as justice. They want Paris to serve hard time, prison-movie style, and a frenzied media is just egging them on. To take just one example, on the cover of its May 21st issue, Star magazine promised exciting details of “Paris’ Prison Hell,” complete with “Lesbian gangs,” “Group Showers,” “Strip Searches,” and “Filthy Bedding.” While it’s good to see the disgraceful conditions that prevail in California’s penal system getting an airing, I doubt that was the motive behind the decision to package the story in quite the way that the Star (and many others) have chosen to do.

Matters reached their squalid climax (so far) thanks to the efforts of the dreadful Joe Arpaio. He’s the publicity hound who doubles up as a sheriff in Maricopa County, Arizona: tents, prisoners in pink underwear eating bologna sandwiches, you know the guy. True to form, he jumped onto the tumbril, offering to host Paris in his desert Guantanamo, an offer that might well, it was speculated, include a stint in a chain gang. Blonde in shackles!

Mercifully, Arpaio’s offer was declined. Hilton, it now turns out, will likely only serve about half her 45-day sentence, and will do so in a unit reserved for those thought to be at risk from their fellow inmates. That this should be necessary is more an indictment of prison conditions than an expression of any particular privilege, but the news has still come as a severe disappointment to far, far too many people

That it does is, in part, a reflection of the very peculiar nature of Paris Hilton’s celebrity. I wish I could say that, in the words of the old joke, she had risen without trace. The reverse is true. Her spoor is everywhere. Since first lurching into view in the early 2000s, she has dazzled the populace and thrilled the media with cubic-zirconia glamour and undeniably genuine sleaze.

Normally, wannabes aiming for the big time hope to do so on the back of talent, looks, achievement, or, at the very least, a winning personality, but Hilton has built her fame — and made quite a bit of cash — on the basis of no obvious achievements, looks that are far from Jolie and a public persona that is dim-witted, bitchy, arrogant, and spoiled.

What she does have is a remarkable talent for self-promotion. In taking advantage of the desperate need of the now web-driven media for content, any content, however tacky, no, preferably tacky, she has served herself up as spectacle for those on whom she so obviously looks down. And it’s worked. “There is,” said Oscar Wilde, “only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about,” and talk, talk, talk, about Paris Hilton we do. If nothing else, this article is evidence of that. As some sort of experiment, the Associated Press tried to avoid publishing anything about her for a few days. In so doing they only added to her fame. She has become an object of fascination, derision, obsession, and, God help us, emulation. And that’s not going to change any time soon. Resistance, AP, is futile.

But if she’s become an icon — and she has — America’s sweetheart, she’s not. There’s something too joyless about her pursuit of pleasure, something too Heather about her pursuit of prestige and, despite occasional Horatia Alger moments, something too Gekko about her pursuit of loot. Sure, her antics are sporadically entertaining, gossip’s equivalent of a five-alarm fire, a really good train wreck, or a particularly bloody bullfight, but we also watch her as phenomenon as much as person. And as we do, we not only use her as a device to proclaim our own cleverness, moral superiority and apple pie niceness, but also, I suspect, as a symbol of, and a scapegoat for, the real excesses and imagined emptiness of this new gilded age. Put all these elements together and we can begin to understand why those grotesque depictions of her dead and dying — unthinkable, probably, in the case of any other celebrity — cause no complaint.

But that’s still no reason to put her on the chain gang.