With the economy floundering, Wall Street in disgrace, and American capitalism facing its most serious ideological challenge in one, two, or three generations (you can take your pick), it's a good moment to remember Lenin.

While the bearded Bolshevik's grasp of economics was never the best and his stock picks remain a mystery, he would have grasped the politics of our present situation all too well. The old butcher would not have found anything especially surprising about the rise of Barack Obama, the nature of his supporters, or the evolution of his policies. He would have simply asked his usual question: Kto/kogo ("Who/whom"). The answer would tell him almost everything he needed to know. Lenin regarded politics as binary--a zero sum game with winners, losers, and nothing in between. For him it was a bare-knuckled brawl that ultimately could be reduced to that single brutal question: who was on top and who was not. Who was giving orders to whom. Hope and Change, nyet so much.

Of course, it would be foolish to deny the role that things like idealism, sanctimony, fashion, hysteria, exhaustion, restlessness, changing demographics, Hurricane Katrina, an unpopular war, George W. Bush, and mounting economic alarm played in shaping last November's Democratic triumph. Nevertheless if we peer through the smug, self-congratulatory smog that enveloped the Obama campaign, the outlines of a harder-edged narrative can be discerned, a narrative that bolsters the idea that Lenin's cynical maxim has held up better than the state he created.

So, who in 2008 was Who, and who Whom?

In a Democratic year, it's no surprise that organized labor emerged as Who and large swaths of the private sector as Whom. Many of the other, sometimes overlapping, constituencies (whether it's minorities, the young, or the gay, to name but three) who saw themselves benefiting from an Obama presidency were equally easy to predict. After all, whether by the accident of his birth or the design of his campaign, Obama's victorious coalition was, even more than most, a creation of meticulously assembled blocks, more pluribus than unum, and each with plenty to gain from his arrival in the White House.

That said, for all the smiles, the reassuring vagueness, and the this-isn't-going-to-hurt (too much) rhetoric, it was somewhat less predictable that a large slice of the upper crust would succumb to Obama's deftly articulated pitch. Yes, it's true that there had been signs that some richer, more upscale voters were being driven into the Democratic camp by the culture wars (and the fact that prosperity had left them free to put a priority on such issues). Nevertheless, even after taking account of the impact of an unusually unpopular incumbent, it's striking how much this process intensified in 2008--a year in which the Democrats were not only running their most leftwing candidate since George McGovern, but also running a leftwing candidate with every chance of winning. Voting for Obama would not be a cost-free virtuecratic nod, but a choice with consequences. At first glance therefore it makes little sense that 49 percent of those from households making more than $100,000 a year (26 percent of the electorate) opted for the Democrat, up from 41 percent in 2004, as did 52 percent of those raking in over $200,000 (6 percent of voters), up from 35 percent last go round.

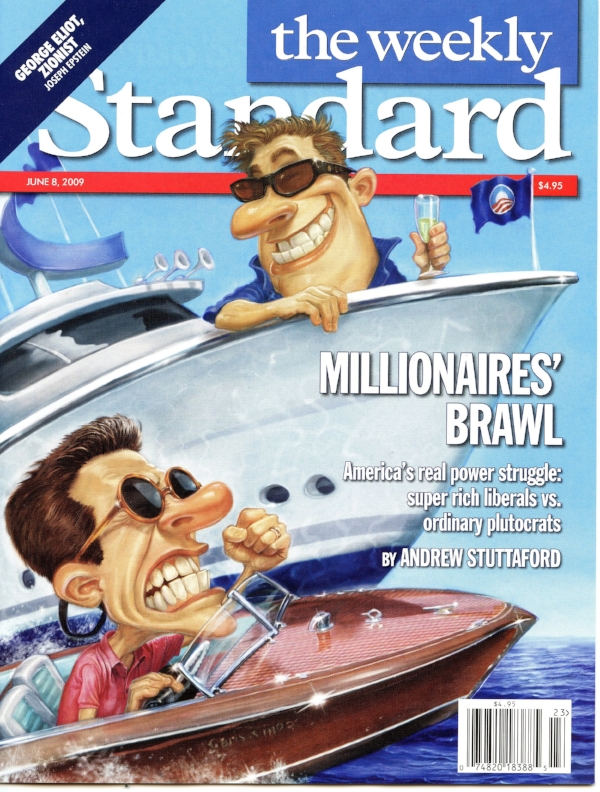

Yet, this shift in voting patterns is more rational than it initially seems: more Lenin than lemming. Class conflict is inherent in all higher primate societies (even this one). It can manifest itself at every level, right up to the very top, and certain aspects of the 2008 campaign came to resemble a millionaires' brawl--one that was, of course, decorous, sotto voce, and rarely mentioned.

In a shrewd article written for Politico shortly after the election, Clinton adviser Mark Penn tried to pin down who exactly these higher echelon Obama voters were ("professional," corporate rather than small business, highly educated, and so on). Possibly uncomfortable with acknowledging anything so allegedly un-American as class yet politically very comfortable with this obvious class's obvious electoral clout, he eulogized its supposedly shared characteristics: teamwork, pragmatism, collective action, trust in government intervention, a preference for the scientific over the faith-based, and a belief in the "interconnectedness of the world." We could doubtless add an appreciation of NPR and a fondness for a bracing decaf venti latte to the list, and as we did so we would try hard to forget this disquieting passage from George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four: "The new aristocracy was made up for the most part of bureaucrats, scientists, technicians, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians."

We are not Oceania, and there's a messiah in the White House rather than Big Brother, but it's not hard to read Lenin, Penn, and Orwell, and then decide that Penn's professionals are the coming Who. They have certainly (at least until the current economic unpleasantness) been growing rapidly in numbers. As Penn relates:

While there has been some inflation over the past 12 years, the exit poll demographics show that the fastest growing group of voters . . . has been those making over $100,000 a year. . . . In 1996, only 9 percent of the electorate said their family income was that high . . . [By 2008] it had grown to 26 percent.

This is a class that is likely to be more ethnically diverse and younger than previous groupings of the affluent--factors that may influence their voting as much as their income. Nevertheless, even if we allow for the fact that there is a limit to how far you can conflate households on $100,000 a year with those on $200,000, there are enough of them with enough in the way of similar career paths, education, and aspirations that together they can be treated as the sort of voting bloc that Penn describes. And it's a formidable voting bloc with a formidable sense of its own self-interest.

That sense of self-interest might seem tricky to reconcile with voting for a candidate likely (and for those making over $200,000 certain) to hike their taxes. In the wake of the long Wall Street boom and savage bust, however, it is anything but. Put crudely, the economic growth of the 1990s and 2000s created the conditions in which this class could both flourish and feel hard done by. Penn hints at one explanation for this contradiction when he refers to the alienating effect of the layoffs that are a regular feature of modern American corporate life. That's true enough. Today's executive may be well paid, sometimes very well paid, but he is in some respects little more than a day laborer. Corporate paternalism has been killed--and the murderer is widely believed to be the Gordon Gekko model of capitalism that Obama has vowed to cut down to size.

But Penn fails to mention (perhaps because it was too unflattering a motive to attribute to a constituency he clearly wants to cultivate) that this discontent stems as much from green eyes as pink slips--as well, it must be added, from a strong sense of entitlement denied. Traces of this can be detected in parts of Robert Frank's Richistan: A Journey through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich (2007), a clever, classically top-of-the-bull-market account of what was then--ah, 2007!--America's new Gilded Age. To read this invaluable travelogue of the territories of the rich (the "virtual nation," complete with possessions, that Frank dubs "Richistan") is to see how the emergence of a mass class of super-rich could fuel growing resentment both within its ranks and, by extension, without. By "without," I refer not to the genuinely poor, who have, sadly, had time to become accustomed to almost immeasurably worse levels of deprivation, but to the not-quite-so-rich eyeing their neighbors' new Lexus and simmering, snarling, and borrowing to keep up. The story of rising inequality in America is a familiar one: What's not so well known is that the divide has grown sharpest at the top. Frank reports that the average income for the top 1 percent of income earners grew 57 percent between 1990 and 2004, but that of the top 0.1 percent raced ahead by 85 percent, a trend that will have accelerated until 2008 and found echoes further down the economic hierarchy.

You might not weep for the mergers-and-acquisition man maddened by the size of an even richer hedge fund manager's yacht, but his trauma is a symptom of a syndrome that has spread far beyond Greenwich, Connecticut. Above a certain level, wealth, and the status that flows from it, is more a matter of relatives than absolutes. The less dramatically affluent alphas that make up the core of Penn's professionals--lawyers, journalists, corporate types, academics, senior civil servants, and the like--suddenly found themselves over the last decade not just overshadowed by finance's new titans but actually priced out of many things they view as the perks of their position: private schools, second homes, and so on. I doubt they enjoyed the experience.

Well educated, articulate and, by any usual measure, successful, they had been reduced to betas--and thus, politically, to a glint in Obama's eye. The decades of prosperity had swollen their numbers, but shrunk their status and their security. Their privileges were mocked or dismantled and their "good" jobs were ever more vulnerable. Wives as well as husbands now had to work, and not just down at the church's charity store either, a change that is more resented than Stepford's children would generally like to admit. Even so, things they felt should have been theirs by rights were still out of reach or, perhaps worse, graspable only by heavily leveraged hands. In a boom-time (July 2006) piece for Vanity Fair, Nina Munk interviewed two women amongst "the worn carpet and faded chintz" of Greenwich's old guard Round Hill Club. They told her how everything had gone downhill, "no one can afford to live here--all our kids are moving to Darien or Rowayton because it's cheaper."

It's a mark of the pressure to keep up that, as Frank noted, in 2004, 20 percent of "Lower Richistanis," those 7.5 million households (the number would be lower now, but it then would have constituted roughly 6-7 percent of the U.S. total) struggling along on a net worth of $1 million to $10 million, spent more than they earned. These poor souls will have included the most prosperous of Penn's professionals, but in an age of "mass luxury" and almost unlimited credit, the compulsion to do whatever it took not to be trumped by the Joneses spread to their less affluent cohorts, with the devastating consequences that were finally visible to all by the middle of last year.

Thus Penn's people had been outbid and outplayed by a rapacious Wall Street swarm of boors, rogues, gamblers, whippersnappers, the plain lucky, and the otherwise undeserving. Then came Wall Street's implosion and these prejudices were reinforced by that hole in the 401(k) and the collapse in the value of that overmortgaged house. Voting left looked better and better.

In 2007, the final financial reckoning was still slouching along waiting to be born. Back then, all they knew was that they had been shoved down the totem pole, which had changed beyond recognition. Nothing that had mattered did, or so it appeared. You can see an echo of this in the opening sections of one of the numerous (and, to be fair, not entirely unmerited) I-told-you-so articles penned by Paul Krugman in recent months:

Thirty-plus years ago, when I was a graduate student in economics, only the least ambitious of my classmates sought careers in the financial world. Even then, investment banks paid more than teaching or public service--but not that much more, and anyway, everyone knew that banking was, well, boring. In the years that followed, of course, banking became anything but boring. Wheeling and dealing flourished, and pay scales in finance shot up, drawing in many of the nation's best and brightest young people (O.K., I'm not so sure about the "best" part).

This social unease bubbled through Tom Wolfe's "The Pirate Pose," a 2007 essay that ran, apparently without irony, in the inaugural edition of Condé Nast's glossy Portfolio magazine, itself a lost artifact of the era when CDOs were still chic. Wolfe's sly--and in its exaggerations accidentally self-revealing--piece opens with an insistent pounding at the door of a Park Avenue apartment. Inside, a genteel lady rises from her "18th-century" (old!) "burled-wood secretary" (tasteful!), "her grandmother's" (old money!), "where she always wrote her thank-you notes" (refined!). Outside rages the absolutely dreadful hedge fund manager with "more money than God" who has just moved into the building:

Ever so gingerly, she opened the door. He was a meat-fed man wearing a rather shiny--silk?--and rather too vividly striped open shirt that paunched out slightly over his waistband. The waistband was down at hip-hugger level because the lower half of his fortyish body was squeezed into a pair of twentyish jeans . . . gloriously frayed at the bottoms of the pant legs, from which protruded a pair of long, shiny pointed alligator shoes. They looked like weapons.

Wolfe had fallen out of love with the Masters of the Universe. The ironic detachment that was one of the many pleasures of The Bonfire of the Vanities had been bumped and buffeted by the author's horror at the barbarians not just broken through the gates, but everywhere he would rather be, something that perhaps explains the faintest trace of glee that runs through this passage:

As for the co-op buildings in New York, their residents having felt already burned by the fabulous new money, some are now considering new screening devices. . . . The board of a building on Park Avenue is now considering rejecting applicants who have too much money.

Wolfe is angry, not so much because of the money (Sherman McCoy wasn't exactly poor), but because these loutish self-styled freebooters do not care for what he enjoys, what he stands for, even for where he might socialize (in his lists of some of the older Upper East Side hangouts, he throws in a couple of the more recherché names--the Brook, the Leash--as a reminder that he knows what's what). They despise what he favors, and even condescension, that traditional last line of defense against the arriviste who does not know his place, is unavailable. How can you condescend to someone who does not care what you think and is richer than you can imagine? The great writer finds himself sidelined on what is, quite literally, his home turf.

This is the class resentment that twists through recent remarks by another writer, a former academic who argued that it was ridiculous that "25-year-olds [were] getting million-dollar bonuses, [and] they were willing to pay $100 for a steak dinner and the waiter was getting the kinds of tips that would make a college professor envious."

The reference to a "college professor" as the epitome of the individual wronged by this topsy-turvy state of affairs is telling: 58 percent of those with a postgraduate education voted Democratic, up from 50 percent in 1992 (those with just one degree split more evenly). If those comments are telling, so is the identity of the speaker: one Barack Obama, a politician who has explicitly and implicitly promised the managers, the scribblers, the professors, and the now-eclipsed gentry that he would finish what the market collapse had begun. He'd put those Wall Street nouveaux back in their place. Higher taxes will claw at what's left of their fortunes and, no less crucially, their prospects. What taxes don't accomplish, new regulation (some of which even makes some sense) and the direct stake the government has now taken in so much of the economy will. Better still are all the respectably lucrative, respectably respectable jobs that it will take to run, or bypass, this new order: Former derivatives traders need not apply.

In an only slightly tongue-in-cheek February column in the New York Times, David Brooks neatly described what this will mean:

After the TARP, the auto bailout, the stimulus package, the Fed rescue packages and various other federal interventions, rich people no longer get to set their own rules. Now lifestyle standards for the privileged class are set by people who live in Ward Three . . . a section of Northwest Washington, D.C., where many Democratic staffers, regulators, journalists, lawyers, Obama aides and senior civil servants live.

If the price for this is a relatively modest (for now) tax increase on their own incomes, it is one the denizens of Ward Three and their equivalents elsewhere will be happy to pay. For it is they now who are on a roll, and every day the news, carefully crafted by the journalists that make up such an archetypical part of Penn's professional class, gets sweeter.

The humbling of Wall Street has made for great copy, but it's fascinating how much personal animus runs through some of the reporting; from the giddy, gloating, descriptions of excess, of bonuses won and fortunes lost, to the oddly misogynistic trial-of-Marie-Antoinette subgenre devoted to examining the plight of "hedge fund wives" and, more recently, "TARP wives" (who had not, of course, been compelled to work).

In his "Profiles in Panic" a January 2009, article for Vanity Fair, Michael Shnayerson wrote:

The day after Lehman Brothers went down, a high-end Manhattan department store reportedly had the biggest day of returns in its history. "Because the wives didn't want the husbands to get the credit-card bills," says a fashion-world insider.

Not quite the guillotine, but the tricoteuses would have relished the story.

And then there's this from the Washington Post's travel section last month:

For so long, they have been taking Manhattan. They as in the Wall Streeters who counted their bonuses in increments of millions. . . . The coveted restaurants, the hotels with infinite thread-count sheets . . . the designer shops that sniff at the idea of a sale--it was all theirs. But the times they-are-a-changin'. . . . Our moment to reclaim the city has arrived. To shove our wallets forward and say, Yes, we can afford this. In fact, give us two.

To anticipate what (other than Ward Three vacationers to Manhattan) is coming next, listen to the increasing talk of congressional investigations (modelled on the FDR-era Pecora hearings) into Wall Street's workings or for that matter an intriguing, much-discussed piece in the Atlantic Monthly by Simon Johnson, a former chief economist for the IMF (Academic: check! Bureaucrat: check!), in which he drew comparisons, not all of them unfair, between the incestuous relationship between Wall Street and Washington and the more overtly corrupt oligarchies he had witnessed abroad in the course of his work. As this analysis finds wider acceptance (and it's too convenient not to), it presages a far greater overhaul of the financial sector than the moneymen now expect and a permanent shift of the balance of power (and the resulting rewards) back in favor of the political class and those who feed off it.

If you think that leaves some of Obama's Wall Street backers in the role of dupes, you're right. But there is a group who are looking smarter by the moment: the tiny cluster that dwells in Upper Richistan (households with a net worth in excess of $100,000,000). If we look at the admittedly sketchy data, there are clear indications that a majority of the inhabitants of Lower Richistan--with their millions but not their ten millions--voted for McCain. However much they might dislike the GOP's social conservatism or hanker after, say, a greener planet, they know that they are not so rich that they can afford to overlook the damage that a high tax, high regulation, high dudgeon liberal regime could do to their wealth, position, and prospects.

The view from Upper Richistan looks very different. The (again sketchy) data suggest that its occupants voted for Obama, as they may well have done for Kerry. Platinum card and red (well, tastefully pink-accented) flag apparently go well together. Warren Buffett's ideological leanings are well known, as are the donations, causes, and preachings of George Soros. Then there was that campaign a few years back by some richer folk (including Soros, Sanka heiress Agnes Gund, and a nauseatingly named grouplet called Responsible Wealth) in defense of the Death Tax. Describing itself as a "network of over 700 business leaders and wealthy individuals in the top 5% of wealth and/or income in the US who use their surprising voice to advocate for fair taxes and corporate accountability," Responsible Wealth is these days busily calling for New York governor David Paterson to increase the tax on "those who can afford it--which means us."

To be sure, neither self-righteousness nor idiocy is a respecter of income, but taken as a whole such efforts are much more than gesture politics, and much more than an updated version of the radical chic so ably described by a younger Tom Wolfe. Many New Jerseyans might think that the very liberal, very rich (thank you, Goldman Sachs) Jon Corzine has been a joke of a governor, but his political career has been all too serious--easily gliding from Wall Street to the U.S. Senate to the governor's mansion--and he's by no means alone. Colorado's high-profile "Gang of Four" (three tech entrepreneurs and a billionaire heiress) may not quite share the politics of Madame Mao's even more notorious clique, but they have been enormously effective in pushing their state into the Democratic camp, and their tactics are sure to be emulated elsewhere. In Richistan, Frank cited a 2004 study that showed that among candidates who spent more than $4 million on their own campaigns, Democrats outnumbered Republicans three to one. Among candidates that spent $1 million to $4 million, Republicans outspent Democrats two to one: more evidence of the political split between Lower and Upper Richistan.

The notion that some of the very richest Americans (not all, of course) support the Democrats should no longer be seen as a novelty. Backing Obama was just the latest chapter in a well-worn story. And it is not as illogical as it might seem. These Croesuses are rich enough scarcely to notice the worst (fingers-crossed) that an Obama IRS can do. They were thus free to vote for Obama, a candidate whose broader policy agenda clearly resonated with many in this nation's elite and who seemed at the time both plausible and unthreatening. The shrewdest or most cynical amongst them will have realized something else, something that an old Bolshevik might call a class interest. The onslaughts on Lower Richistan and on Wall Street will make it more difficult for others to join them at mammon's pinnacle and thus to compete with them economically, politically (particularly in an era when McCain-Feingold has greatly increased the importance of being able to self-finance a campaign), and socially.

Who/whom indeed.