True lies

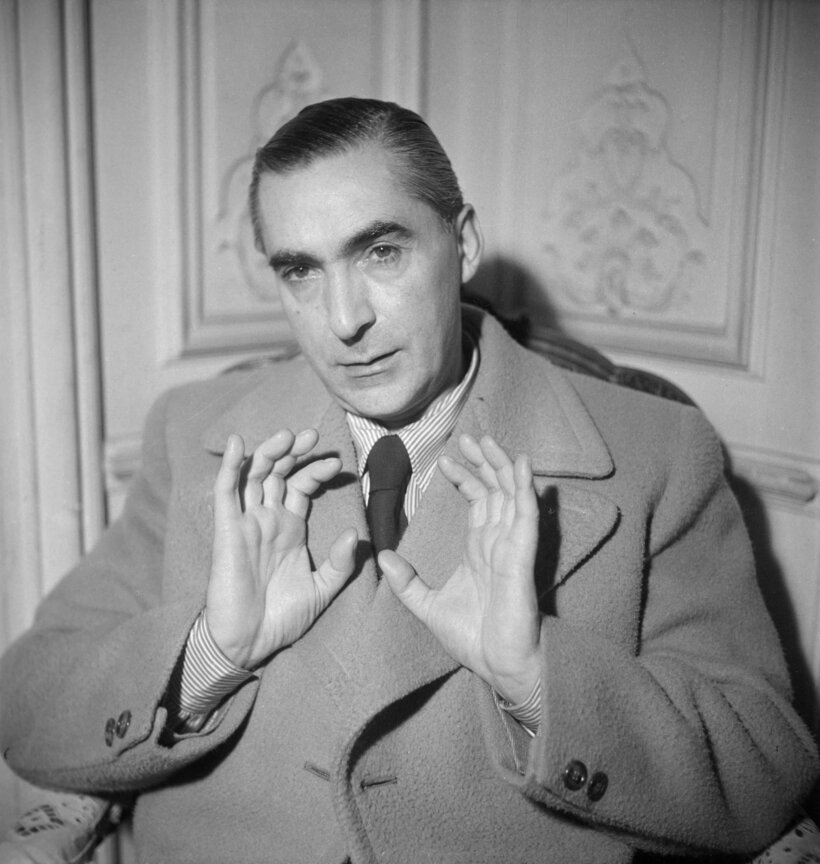

Curzio Malaparte - Diary of a Foreigner in Paris

The New Criterion, September 1, 2020

Curzio Malaparte, born Kurt Erich Suckert (1898–1957), was a fabulist, a trickster, and a master of obfuscation, talents that served him well on the page and, as he slid away from his fascist past, in later life too. It is thus not inappropriate that the first English-language edition of the “diary”—I’ll get to those scare quotes in due course—of his time in early post-war Paris draws on two differing predecessors. The first (Diario di uno straniero a Parigi) came out in Italy in 1966, the second in France the following year. Stephen Twilley, who has now translated the Diary into English, notes that the typewritten manuscript delivered to the Italian publisher by Malaparte’s family was in chaos. The French editors complemented chaos with carelessness and—when Malaparte was less than respectful about some members of France’s cultural establishment—censorship.

Twilley thinks that “there must be at least two versions of more than half of the Diary.” With no access to primary sources, his version is a “sort of hybrid.” It involved reconciling (and sometimes supplementing or correcting) the two earlier editions, neither of which is “particularly authoritative.”

That can be said of other significant portions of Malaparte’s work, although for them death cannot provide an excuse. The original reports Malaparte filed for the Corriere della Sera from the Axis and Finnish sides of the Eastern Front (some of which were actually written in rather more comfortable Rome or Capri) were destroyed in an Allied bombing raid. This happy obliteration allowed Malaparte to claim that the reports that are the basis of the definitive edition of Il Volga nasce in Europa (The Volga Rises in Europe, 1952)—in my minority opinion, his greatest work—also included passages written by the bravely outspoken correspondent who had previously fallen foul of the censor. Maybe.

Then there are the questions surrounding another of Malaparte’s books about the war, the extraordinary Kaputt (1944). Widely considered Malaparte’s masterpiece, this (in his words) “horribly gay and gruesome” work is highly (and understandably) critical of its author’s (former) German allies. Indeed, in a preface, Malaparte explains how, with the help of suitably grand friends—another Malaparte trademark—the book was smuggled in pieces across Europe, to be reassembled in a liberated Italy. In reality, it appears that the tone of the original manuscript was anti-English rather than anti-German. The later iteration was only written after Malaparte had switched sides (he had attached himself to the Americans, battling their way up Italy. Before long, he would be making overtures to the Communist Party).

While Malaparte’s casual relationship with the truth was opportunistic, he enjoyed, I believe, the games that went with it. In La pelle (The Skin, 1949), Kaputt’s sequel, and another of what he described as his “novels of biographical reportage,” “Malaparte” is challenged over a lunch with French officers just before the liberation of Rome about the accuracy of some of Kaputt. An American officer, “Jack,” comes to his defense with the argument that “It is of no importance whether what Malaparte relates is true or false . . . the question is whether or not his work is art,” a defense which Malaparte both subverts and acknowledges both within the text—he subsequently reveals to Jack how he has fooled his lunch partners with a characteristically grotesque hoax—and outside it. Kaputt was published after the liberation of Rome, a fact that only the most observant of readers will have noticed, meaning that Malaparte was lying about being accused of lying and, presumably, also about the lie with which he purported to prove the French officers’ point.

Malaparte’s—how shall I put this—unreliability was soon not much of a secret, something he implicitly acknowledges in the first sentence of another unfinished, posthumously published work, Il ballo al Kremlino (The Kremlin Ball, 1971), inspired by a trip to the USSR in the late 1920s. “In this novel,” he maintains, “everything is true: the people, the events, the things, the places,” a self-contradictory overture made even more absurd by what follows. Thus he comes across a fallen prince of the old order, who, the historical record shows, was already dead, and he meets a falling princess—Trotsky’s sister—of the new order, who was well on the way to being so: “A subtle odor of dead flesh spread through the room.” She was shot some years later.

In the “Sketch of a Preface” to Diary of a Foreigner, Malaparte makes clear that this “diary” (Malaparte uses the scare quotes too) was also intended as a work that slipped between categories:

Every “diary” is a portrait, chronicle, tale, record, history. Notes taken day by day are not a diary but merely moments selected at random in the current of time, in the river of the passing day. A “diary” is a tale . . . . A diary, like every tale, calls for a beginning, a plot and a denouement.

In fact, argues Malaparte, it is much like a novel or a play, “but centered on the character called ‘I.’ ”

And “I” had no intention of abandoning his games with truth. Malaparte recalls telling an anecdote about first meeting Mussolini. It concludes with him insulting the dictator for his choice in ties. A listener, a Colonel Cumming, observes that “Malaparte’s stories are made from nothing, but he tells them well.” By repeating this amiable heckle Malaparte raises a question over the whole story, a question simultaneously undermined and reinforced by the fact that Cumming’s comment is suspiciously similar to that allegedly made by Jack, another American officer, who was modeled on a Colonel Cumming who died in Italy . . . in 1945.

Malaparte described the Diary as being, in part, “a portrait of a moment in the history of the French nation, of French civilization.” And so it is. Amid interminable rambling about the malign impact of Cartesian thinking on the French, a vivid picture emerges of a France still broken by the German occupation. Malaparte, referring to the foreign occupations of other peoples—including his own—over the centuries, sees this as an exercise in self-abasement: an unsympathetic observation so soon after the Panzers had been driven out, but a reflection, possibly, of the disappointment felt by this lifelong Francophile, and lifelong narcissist, that France appeared to be disappointed by him.

Malaparte had fought for France on the Western Front in the First World War (before Italy had joined the conflict), and before a brief stint as an invader in 1940—the subject of his Il sole è cieco (1947)—stayed there on many occasions in the interwar years. Notably, he was one of the Italian delegation to the Versailles conference, later returning again in the mid-1920s, when he became, in Twilley’s words, “the most prominent Fascist intellectual in Paris,” a role he combined with keeping an eye on the Italian émigré community.

Malaparte returned to the French capital in the early 1930s. His Technique du coup d’État (1931—it was not published in Italian until 1948), a cynical analysis of what it takes to make a revolution, writes Twilley, “put him at the center of the French political and literary scene, ushering him into the grand salons of the age.” A work about Lenin, Le Bonhomme Lénine (1932), kept him there.

Despite the success of Kaputt, Malaparte never regained that position in the Paris of the 1940s. There was too much to explain away, and his efforts to do so were too offensive, too defensive, or too evasive to do the trick.

Many participants in the cultural scene kept their distance or worse:

When I got to Cli Laffont’s, Albert Camus was already there, seated on a sofa between two young women. I immediately noticed that he was looking at me with hate. He had an unremarkable tie and an unremarkable hate. I immediately strove not to judge him by his tie, but by his books.

Ties, again.

It is not hard to appreciate why Camus, a veteran of the Resistance, might have felt this way. Even as he publicly moved to the left, Malaparte’s break with fascism never seemed entirely clear cut, an impression, if inadvertently, bolstered by the Diary. Malaparte stresses that his opposition to fascism predated the fall of Mussolini, a claim backed up by tales of imprisonment and exile that were at best exaggerated, at worst fictitious, and, with the exception of one failed intrigue, had little or nothing to do with politics. While the Diary is by no means a complete account of Malaparte’s time in Paris (it contains almost nothing on his literary or—a new detour—theatrical activities), it may be telling that there is nothing on his sending funds to Louis-Ferdinand Céline, a brilliant writer, disgraced by anti-Semitism and collaboration, then skulking in prudent, if impecunious, exile in Denmark. That said, Malaparte does reveal that at least some of his socializing was with individuals sullied by the war years.

Equally, while the single strongest passage in the Diary revolves around a story that highlights both the cruelty of anti-Semitism and the cowardice of those who went along with it, there are sentences that suggest that Malaparte’s disturbingly high level of detachment (a characteristic, incidentally, he shared with another foreigner in Paris, the Wehrmacht’s Ernst Jünger, a fellow Francophile, whose diaries include descriptions of part of the French capital’s intellectual milieu under the occupation) was capable of corroding into something infinitely more sinister. His reference to a “herd” of Jews just a few years after millions of Jews had been herded to their deaths would be disconcerting enough in its own right without a handful of other comments about “Jews” in a text that, as so often with this writer, leaves the reader wondering quite who Curzio Malaparte really was.

Most unsettling, arguably, is the way he embellishes “The Rats of Jassy,” one of the most powerful chapters in Kaputt. In it, “Malaparte” witnesses the build-up to the mass murder of Jews in Jassy (Iași), a Romanian city, the slaughter itself, and an aftermath that points clearly to the nature of the Holocaust then gathering pace. In reality, as Maurizio Serra demonstrates in his definitive biography, Malaparte: Vies et Légendes (2011), Malaparte arrived in Jassy after the killings, but in Kaputt, a book in which the borders between truth and fiction are unpoliced, this matters less than what Malaparte was trying to say (at, in terms of popular understanding, a relatively early stage) about the evil that had been unleashed in Europe.

In the course of a bizarre conversation (which, as always with Malaparte, may or may not have happened) recorded in the Diary, about his wish to put a rose in the dead hand of Mussolini, “to be kind to him in death,” Malaparte tells of how the “morning after” the Jassy massacre, he saw “a hundred or so dead children” laid out on a sidewalk:

They were Jewish children, murdered. Their little hands were tightly closed . . . . I went into Kane’s grocery, just down the street, bought a packet of candy, and put a piece of candy into the hand of each child. There was nothing else I could do . . .

In “The Rats of Jassy,” “Malaparte” is depicted as a ditherer in the face of impending atrocity. The real Malaparte’s repetition of the (false) claim that he was in that city at the time of the bloodletting, however, could easily be seen by his interlocutors as a confession that he had also displayed the unforgivable insouciance described in Kaputt, a confession made all the more persuasive by the fact that Kaputt was taken much more literally in the 1940s than it is now. He then compounds this with the tale of the candy that, to anyone with any taste, puts him in an even worse light still. Then again, that gesture was so self-evidently unlikely that the only sensible conclusion to be drawn is that the butchered children, who, in one sense, were real enough—there was, after all, a pogrom in Jassy—were props in a story fashioned by Malaparte in his endless desire to shock. It is easy to see how he was influenced by the conventions, if not the politics, of the surrealism of that era: in his writing about the war, the razor is never too far from the eyeball.

For the most part, this diary is a work for Malaparte completists who will pass over the fatuous philosophizing to savor again the dropping of aristocratic names, the wildly unreliable gossip, the unexpected erotic tangents (armpits!), and of course the old lies, so many of them, sometimes with extra embellishment, sometimes pristine. Confined for his efforts “for the common cause of freedom”? No. Arrested by the Germans and sentenced to four months imprisonment for his reporting from the Eastern Front? No, not that either.

Even those unfamiliar with Malaparte’s work ought to appreciate his gift for the striking image (“Later, descending the staircase, I encountered Mme Ducaux, followed by her wolf”) and for a power of description in which there is gold beneath the glitter:

Those deep black eyes, where genius and old age already contended.

Or:

Mirrors filled with dusty light.

Or, looking backing at the Edwardian belle époque, “that . . . refined age, which Edward VII had illuminated with his skeptical and indulgent smile,” words that could never have been written about Edward the Caresser’s dreary successors.

And for all Malaparte’s blather, there are some fascinating insights in the Diary, not least on the fading of Europe from the world stage:

Paris, like a large part of Europe, is now undergoing the crisis that the Orient underwent in its time, that of passing from the living and acting world of history to the bleak, passive, resigned world of historical fatalism.

Those looking to understand the creation of what became the European Union could do worse than starting there.

But, as with so much of Malaparte’s work, the high points are the extended anecdotes, including that meeting with Mussolini and a haunting tale of a group of Spanish soldiers—orphans of the civil war—who had joined the Red Army only to be taken prisoner by the Finns near Leningrad. Then there is an encounter with an old man and a child in the Tuileries Garden, both blind from birth. The duo have invented an exotic, enchanting world all their own, into which “Malaparte” intrudes, the habitual liar who reveals a banal truth and by doing so becomes, albeit accidentally, some sort of villain, a story that, coming from Malaparte, may—or may not—come with a deeper message.

But these are all eclipsed by “The Ball of Count Pecci-Blunt,” which was probably written as part of Una tragedia italiana, an unfinished novel (although the count was real enough) Malaparte had begun in the 1930s. It describes an act of magnificent defiance in the face of the passing of anti-Semitic laws in Italy. It gradually builds up to a lengthy passage of astonishing beauty too lovely to mutilate with an extract, before reaching a delicately devastating conclusion.

“It is of no importance whether what Malaparte relates is true or false,” said “Jack” just outside Rome, “the question is whether or not his work is art.” At Malaparte’s best, it is something greater than that. At his worst, well . . .