Macbeth’s Two Ghosts

Of all Shakespeare’s ghosts, perhaps the most terrifying is the “horrible shadow” of the murdered Banquo, invisible to all but the tyrant who arranged his killing, a bloodstained reproach, a dreadful warning — the incarnation of a guilt which, like the victim himself, will not fade away. Its appearance is the astoundingly choreographed centerpiece of a remarkable newMacbeth that transferred from the U.K. to New York earlier this year (it has now moved from the Brooklyn Academy of Music to Broadway’s Lyceum Theater). This Macbeth,(directed by Rupert Goold and with Patrick Stewart in the starring role) is an enthralling, hectic, cacophonous triumph, a vivid portrait of a collapsing natural, moral, and political order that manages both to honor Shakespeare’s hideous hurlyburly of power, psychosis, and evil while overlaying it with allusions to a fouler tyrant from a later even more terrible time. And, no, this is not yet another crass “modernization” of a play that needs none: our understanding of both Macbeth and the despot to come is refreshed, deepened, and jolted.

A first-rate cast does all that it can to assist. So, for example, the austerely attractive Kate Fleetwood is unbearably, irresistibly watchable as an unnerving and ultimately unnerved Lady Macbeth, the fourth of the four women who lure, in one way or another, the Thane of Cawdor to his doom; while Christopher Patrick Nolan as Seyton, a leering thug with a stink of sulfur about him (the sound of his name is all too fitting) becomes the embodiment of how low Macbeth will sink in order to hang on to his ill-gotten crown. That’s never lower than when Macbeth orders the murder of his rival Macduff’s family, a slaughter that reduces Macduff to a level of misery that would be unthinkable if Michael Feast didn’t make it so real:

All my pretty ones? Did you say all? O hell-kite! All? What! All my pretty chickens and their dam

At one fell swoop?

Above all, this is a drama that revolves around an extraordinary performance by Stewart, a light year or two away from the Starship Enterprise, but still very much in command. From the moment that we first see him, he dominates the stage, sometimes obviously, as a military man reveling in victory, sometimes subtly as he steels himself for regicide or, finally, despairingly, as he yields to defeat.

The most distinctive thing about this Macbeth may be the way that it is haunted not by one ghost, but two. We never see the second. It is glimpsed only in hint, in gesture, in the laughter that accompanies a savage joke, in flickering newsreel of past parades and, mostly, in our own memories of the cruelties of all our day-before-yesterdays, cruelties which Shakespeare never lived long enough to see — except, perhaps, in his imagination — but which we will not, should not, live long enough to forget.

The first traces of this malign presence can be detected in the appearance of the soldiers in the opening scenes: leather coats, leather boots, flat caps, uniforms more usually associated with Kursk than Cawdor, with cattle trucks rather than cavalry. It’s evoked again by the basement, moral and physical, within which the action unfolds, a miserable space that does duty as hospital, kitchen, torture chamber, bar, palace, banqueting hall and (underlining the way that this play never escapes the lower depths — even when the drama supposedly moves outside) the moors, forests, and battlefields of Macbeth’s much contested kingdom. Huis Clos. No exit. This bunker, this arena is a bleak, clinical, claustrophobic place, its white-tiled walls efficient in a cheerless mid-century way, easy to swab down after who knows what. It’s best reached by an old-fashioned concertina-gated elevator, a mechanized entrance to some sort of hell, to the Lubyanka of our nightmares.

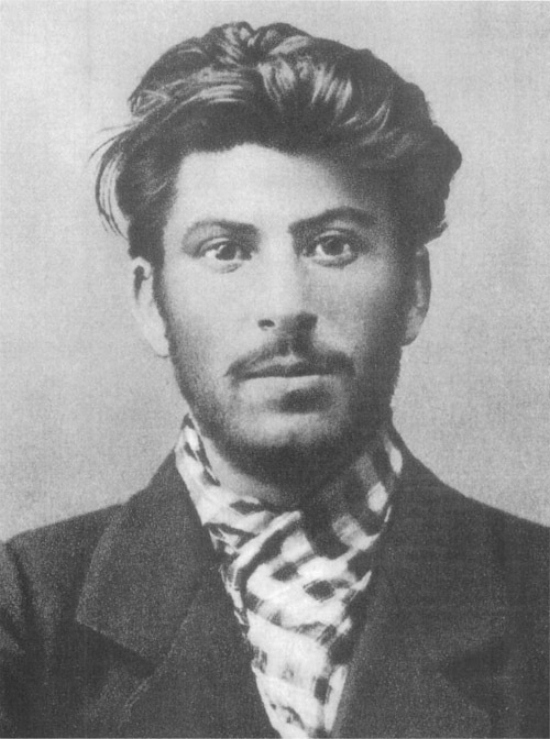

But it’s when we arrive at the play’s core, with Macbeth ascendant and regnant, the former king dead, and the search for traitors well underway, that this second ghost, that of Joseph Stalin, comes closest into view. Beyond a moustache, Stewart never really attempts impersonation; The rest is just suggestion, the sometimes uncanny resonance of the play’s own lines, and the adroit use that Goold makes of the gaps left between them. Thus we see Macbeth making his plans in the wake of what has clearly been a good day out at the hunt. He is pleasant, cheery, his hat pushed back at the casual angle that Stalin (a man who could pantomime relaxation) sometimes favored when out in the field. He is holding a shotgun, and as he talks, he jovially swings the weapon out towards the audience, pointing here, pointing there, randomly, precisely, playfully, maliciously, aiming at you, at me, at Banquo, at Duncan, at Bukharin, at Trotsky, at tens, at thousands, at millions.

And when Macbeth orders Banquo killed he does so in a light, conversational tone, apparently as preoccupied with the making of a sandwich as the planning of an assassination. As for Stalin, well, he could sign death lists condemning thousands and then take in a movie, something light, a comedy perhaps, to round off an undemanding day. When Banquo is eventually butchered, he is murdered in plain sight, cut down in a crowded railroad car. His executioners know that in Macbeth’s police state no-one will dare intervene. They don’t. As Khrushchev once asked in a not so different context, would you?

Banquo returns, of course, as ghost to feast, but until that moment, it is Macbeth who is in charge that evening, expansive, welcoming, a “humble host,” but still taking care to remind his guests that they owe their seats at the table to him. It’s a point brilliantly underlined by the way that Stewart takes the time, leisurely, elaborately, and sadistically, to take a cigarette from the mouth of one of his guests (Lennox) and then crumble its contents over the man’s motionless head. Lennox (Mark Rawlings) may be a thane, a noble, but under the new regime, he is, to borrow Khrushchev’s phrase for members of Stalin’s entourage, just another “temporary person.” The thane sits rigid, a deer caught in the headlights with darkness, maybe, just ahead.

It’s an interlude that owes nothing to Shakespeare and, I imagine, everything to Stalin, whose soirées, if that’s the word, were master classes in the uses of humiliation. In Stalin: Court of the Red Tsar, Simon Sebag Montefiore explains how they went:

Sometimes Stalin himself “got so drunk he took such liberties,” said Khrushchev. “He’d throw a tomato at you.” [Secret police chief] Beria was the master of practical jokes along with Poskrebyshev. The two most dignified guests, Molotov and Mikoyan, became the victims as Stalin’s distrust of them became more malicious. Beria targeted the sartorial splendor of the ‘dashing’ Mikoyan. . . . [H]e slipped old tomatoes into Mikoyan’s suits and then ‘pressed him against the wall’ so they exploded in his pocket. . . . Beria once wrote “PRICK” on a piece of paper and stuck it on Khrushchev’s back. When Khrushchev did not notice, everyone guffawed. Khrushchev never forgot the humiliation.”

No he didn’t. He organized Beria’s execution within months of Stalin’s death. It’s not too long either before Lennox is plotting against Macbeth. The indignities inflicted by Stalin upon his clique are historical fact, the shift in Lennox’s loyalty is Shakespeare, but the way the two narratives, one real, one not, are woven together by Goold brings the former to life, and an extra dimension to the latter. It’s a rare example of the director monkeying with Macbeth’s original storyline, and it’s notable that it only affects a relatively minor player. For the most part Goold is simply content to add subtext, ornamentation, a touch of gimmickry (the moment the Weird Sisters decide to start rapping their way through their incantations is not a success), and some interpretation. The play’s dark heart is left largely untouched. Shakespeare is allowed to be Shakespeare. The Soviet theme is there for those who want to make something of it, but it’s an enrichment, not an intrusion. It’s a device to illuminate, not distort.

Thus the murder of Macduff’s wife and children, butchered not “for their own demerits” but for his, is shocking as theater, and monstrous as a prelude of what history had in store. The killing of the kin of the enemies (real or presumed) of the Soviet state might still have been shocking, but it certainly wasn’t rare. And then there is this, a description of Scotland under Macbeth’s brutal rule:

Alas! Poor country;

Almost afraid to know itself. It cannot

Be call’d our mother, but our grave; where nothing,

But who knows nothing, is once seen to smile;

Where sighs and groans and shrieks that rent the air

Are made, not mark’d; where violent sorrow seems

A modern ecstasy.

Stalin’s gargoyle utopia could be described no better.

But this is still Shakespeare’s Macbeth, not Solzhenitsyn’s. The differences between Scottish king and Soviet dictator are, in a way, almost as haunting as the similarities. In the early scenes of the play, Macbeth is, famously, a hesitant killer, whose sense of guilt then never — quite — disappears. In this production, his final moments are freighted with an exhausted hopelessness that goes further than anything in the original play. Stalin, by contrast, got where he did by doing what it took, unprompted, remorselessly, and with no signs of a conscience. In a sense he was his own Lady Macbeth. He died raging, unrepentant, and in charge, a figure so dangerous that, once stricken, it was hours before anyone even dared enter his room. He got away with his crimes, but now, at least, we have a Shakespeare to remind us what they were.

See it while you can.