The notebooks—worn, creased, and drab, but haunting nonetheless—lay carefully set out on a table in the lobby of a New York hotel. Their pages were filled with notes, comments, and calculations, jotted and scribbled in the cursive, spiky script once a hallmark of pre-war Britain's educated classes. Their author had, it seems, wandered through a dying village deep within Stalin's gargoyle empire. "Woman came out and started crying. 'They're killing us. In my village there used to be 300 cows and now we only have 30. The horses have died. How can I feed us all?'" It was the Ukraine, March 1933, a land in the throes of a man-made famine, the latest murderous chapter in Soviet social engineering. Five, six, seven million had died, maybe more. As Khrushchev later explained, "No one was counting."

But how had these notebooks found their way to a Hilton in Manhattan? Some years ago, in a town in Wales, an old, old lady, older than the century in which she lived, was burgled. As a result, she moved out of her home. When her niece, Siriol, came to clear up whatever was left, she found a brown leather suitcase monogrammed "G.V.R.J." and, lying under a thick layer of dust, a black tin box. Inside them were papers, letters, and, yes, those notebooks ("nothing had been thrown away"), the last records of Gareth Jones—"G.V.R.J."—Siriol's "jolly," brilliant Uncle Gareth, a polyglot traveler and journalist. In 1935 he had been killed by bandits in Manchuria, or so it was said. All that was left was grief, his writings, and the memory of a talented man cut down far, far too soon.

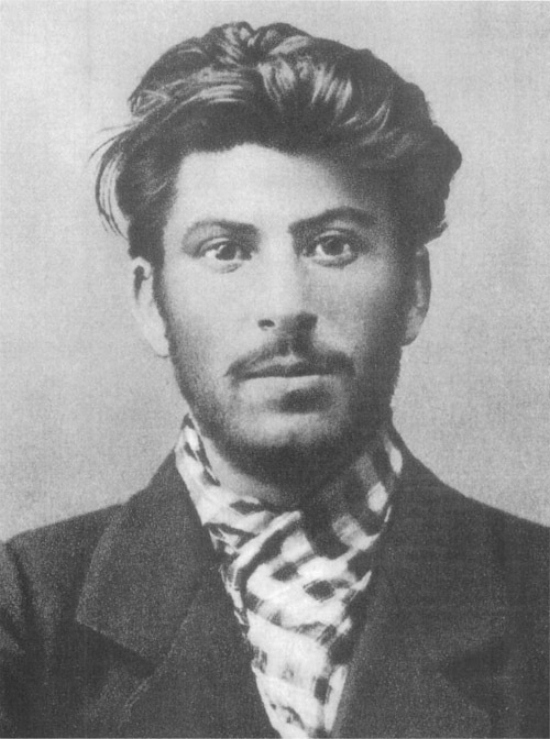

Seven decades later, as I sat talking to Siriol Colley in that midtown hotel, looking through Jones's papers, his press clippings, even his passport, it was not difficult to get a sense of the uncle she still mourned. Welsh to his core, he was typical of those clever, energetic Celts who did so well in the British Empire, restless (all those visa stamps, Warsaw, Berlin, Riga . . .), ambitious, and enterprising. Despite his youth, Jones seemed to get everywhere, Zelig with a typewriter. On New Year's Day 1935, for instance, he was in San Simeon, Kane's Xanadu itself, side by side with William Randolph Hearst. Earlier, we find him on a plane with Hitler ("looks like a middle-class grocer"), and, why, there he is, smiling on the White House lawn in April 1931, standing just behind a hopeless, hapless Herbert Hoover.

Above all, this man who reportedly charmed his captors in Manchuria by singing them hymns, was what the Welsh call “chapel”: pious, hardworking, teetotal, a little priggish, and armed with a sense of right and wrong so fierce that it gave him the strength to report the truth of what he saw, at the cost, if need be, of his career and, some would say, his life. Jones’s politics were typically chapel too, steeped as they were in the Liberal traditions of Welsh Nonconformism. Ornery, high-minded, pacifist, egalitarian, a touch goofy, a little bit utopian, Jones was just the sort of Westerner who might have been attracted to the Soviet experiment. And so he was—initially. In a 1933 article for the London Daily Express, Jones recalled how “the idealism of the Bolsheviks impressed me . . . the courage of the Bolsheviks impressed me . . . the internationalism of the Bolsheviks impressed me,” but “then,” he added, “I went to Russia.”

And there, for Jones, everything changed. His accounts of his visits to the USSR (the first was in 1930) are a chronicle of mounting disillusion. Reading them now, particularly the occasional attempts to highlight some Soviet achievement or other, it’s easy to see that this young Welsh liberal, this believer, wanted to trust in Moscow’s promise of a radiant future, but Communist reality—dismal, savage, and hopeless—kept intruding. Unlike many who came to inspect the people’s paradise, he reported on its dark side too. For Jones, there was no choice. It was the truth, you see.

By the autumn of 1932, Jones was sounding the alarm (“Will There Be Soup?” and “Russia Famished Under the Five-Year Plan”) about the catastrophe to come: “The food is not there.” Early the next year, he returned to Moscow to check the situation for himself, took a train to the Ukraine, and then walked out into the wrecked, desperate countryside. Once back in the West, he wasted no time, not even waiting to get back home before telling an American journalist in Berlin what he had seen: Millions were dying.

Soviet denials were to be expected. That they were supported by the New York Times was not. The newspaper’s Moscow correspondent, Walter Duranty, reassured his readers that Jones had been exaggerating. The Welshman was, he condescended, “a man of a keen and active mind . . . but [his] judgment was somewhat hasty . . . It appeared that he had made a forty-mile walk through villages in the neighborhood of Kharkhov and found conditions sad.” Sad—not much of an adjective, really, to describe genocide.

The Times’s man, who had won a Pulitzer the previous year for “the scholarship, profundity, impartiality, sound judgment and exceptional clarity” of his reporting from the Soviet Union, did not share Jones’s sense of “impending doom.” Yes, “to put it brutally,” omelettes could not be made without breaking eggs, but there had been “no actual starvation or deaths from starvation.” Duranty came, he claimed, to this conclusion only after “exhaustive enquiries about this alleged famine situation,” but other discussions probably influenced him more. The big story in Moscow in the spring of 1933—bigger by far than the death of a few million unfortunate peasants—was the pending show trial of six British engineers. Courtroom access and other cooperation from Soviet officialdom would be essential for any foreign journalist wanting to satisfy the news desk back home. That would come at a price. The price was Jones.

Eugene Lyons, another American journalist in Moscow at the time, later explained that “throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes—but throw him down we did, unanimously and in almost identical formulas of equivocation. Poor Gareth Jones must have been the most surprised human being alive when the facts he so painstakingly garnered . . . were snowed under by our denials.” According to Lyons (not always, admittedly, the most reliable of witnesses, but the essence of his tale rings true), a deal was struck at a meeting between members of the American press corps and Konstantin Umansky, the chief Soviet censor. “There was much bargaining in a spirit of gentlemanly give-and-take . . . before a formula of denial was worked out. We admitted enough to soothe our consciences, but in round-about phrases that damned Jones as a liar. The filthy business having been disposed of, someone ordered vodka and zakuski.” Spinning a famine was, apparently, thirsty work.

Undaunted by the attacks on his accuracy, Jones intensified his efforts. There were articles in the Daily Express, the Financial Times, the Western Mail, the London Evening Standard, the Berliner Tageblatt, as well as a lengthy letter to the Manchester Guardian in support of Malcolm Muggeridge, who had, like Jones, told the truth about the famine and, like Jones, been vilified in return (suggestions that there was starvation in the USSR were, said George Bernard Shaw, “offensive and ridiculous”). In a letter published by the New York Times in May 1933, Jones hit back at Walter Duranty. The reports of widespread famine were, he wrote, based not only on what he had seen in the villages of the Ukraine, but also on extensive conversations with other eyewitnesses, diplomats, and journalists. After a few polite remarks about Duranty’s “kindness and helpfulness,” the tone turned contemptuous. Directly quoting from Duranty’s own dispatches, Jones charged that censorship had turned some journalists into “masters of euphemism and understatement . . . [They] give ‘famine’ the polite name of ‘food shortage’ and ‘starving to death’ is softened down to read as ‘widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition.’. . . Mr. Duranty says that I saw in the villages no dead human beings nor animals. That is true, but one does not need a particularly nimble brain to grasp that even in the Russian famine districts the dead are buried . . . [T]he dead animals are devoured.”

Moscow responded by barring Jones from the USSR. He was cut off for good from the site of the story he had made his own. Duranty received a rather different reward. Some months later he accompanied the Soviet foreign minister on a trip to America, a journey that was to culminate in FDR’s decision to extend diplomatic recognition to the Communist regime, a decision that was fêted, fêted in that famine year, with a celebration dinner at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel, at which Duranty was honored with cheers and a standing ovation. On Christmas Day 1933 came the greatest prize of all—an interview with Stalin himself. Well, of course. It was a reward for work well done. Duranty had, said the dictator, “done a good job in . . . reporting the USSR.”

But history had not yet finished with Gareth Jones. The young Welshman possessed, explained David Lloyd George, the former prime minister for whom Jones had, some years before, worked as an aide, “a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk.” So, it’s no surprise to find him in Japan in early 1935, interviewing, questioning, snooping, and perhaps attracting the sort of attention that could turn out to be fatal. By July that year he was heading through the increasing chaos of northern China toward Japanese- controlled Manchuria (Manchukuo). On July 26, Jones updated the narrative he was writing for the last time. He was, he wrote, “witnessing the changeover of a big district from China to Manchukuo. There are barbed-wire entanglements just outside the hotel. There are two roads . . . [O]ver one 200 Japanese lorries have traveled; the other is infested by bad bandits.” Two days later, the bandits struck. Jones was kidnapped. He was murdered two weeks later. It was the eve of his 30th birthday.

We will probably never know who was ultimately responsible for Jones’s death. There had been a ransom demand, and so, perhaps, this was just a kidnapping that went horribly wrong. There are, however, other possibilities. The Japanese would certainly not have welcomed a Westerner watching the takeover of yet another Chinese province, and there is some evidence that the kidnappers were under their control. It’s also intriguing to discover that one of Jones’s contacts in those final days was linked to a company now known to have been a front for the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police. To Lloyd George, only one thing was clear: “Gareth Jones knew too much.”

And if he knew too much, the rest of the world understood too little. For decades, like the dead whose story he told, this lost witness to a genocide seemed doomed to be forgotten, a family tragedy, a footnote, but now that’s changing. Jones is at last returning to view, thanks in no small part to the efforts of the indefatigable Siriol Colley, the author of a book about her uncle—and a second is on the way. (Colley’s son Nigel has also set up a website: www.colley.co.uk/garethjones/index.html.)

One thing, however, has not changed. On December 4 last year, not long after the Pulitzer committee decided that Duranty should retain his prize, Colley wrote to the New York Times asking whether the paper could at least issue a public apology for the way in which its Moscow correspondent had smeared Jones. She’s still waiting.