With Her People

Rebecca Schull: On Naked Soil - Imagining Anna Akhmatova

National Review Online, May 23, 2008

When, in 2005, Vladimir Putin labeled the collapse of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the last century,” he was only confirming the fact that Russia’s understanding of its Communist past is once more in flux. History is again being rewritten, distorted, and manipulated — this time in the interest of creating a national narrative in which all Russians can, supposedly, take pride. The crimes of the fallen dictatorship are being shrouded in comforting patriotic myth, or, increasingly, just denied.

In the West, by contrast, there are signs that Joseph Stalin, the most monstrous of all the Soviet despots, may finally be penetrating public consciousness as an embodiment of an evil that has rarely, if ever, been equaled. Within this context, it’s interesting to note that New Yorkers could have seen not one, but two, evocations of Stalinism on stage this April. The remarkable Rupert Goold/Patrick Stewart Macbeth-as-Stalin attracted more attention, and deservedly so. Nevertheless it would be wrong to overlook a quietly effective production at the Theater for the New City where the focus rested mainly on just one of the “wonderful Georgian’s” victims. On Naked Soil: Imagining Anna Akhmatova is a new play by Rebecca Schull (yes, Fay from Wings,but also the author of an earlier drama about the Gulag memoirist Eugenia Ginzburg) revolving around Anna Akhmatova, the poetess who was among the most eloquent of all the witnesses to the atrocities of the regime that tormented, stifled, but never quite destroyed her:

In the fearful years of the . . . terror I spent seventeen months in prison queues in Leningrad. One day somebody “identified” me. Beside me, in the queue, there was a woman with blue lips. She had, of course, never heard of me; but she suddenly came out of that trance so common to us all and whispered in my ear (everybody spoke in whispers there): “Can you describe this?” And I said: “Yes I can.” And then something like the shadow of a smile crossed what had once been her face.

And describe it she did, in lines of hideous beauty and terrible sadness:

In those years only the dead smiled,

Glad to be at rest: And Leningrad city swayed like

A needless appendix to its prisons.

It was then that the railway-yards

Were asylums of the mad;

Short were the locomotives’

Farewell songs.

Stars of death stood

Above us,

and innocent Russia

Writhed under bloodstained boots, and

Under the tires of Black Marias.

On Naked Soil shuttles back and forth between two eras, the late 1930s and the early 1960s, but it is the former, deep in those “fearful years,” that define it. The play opened with Akhmatova (Ms. Schull) alone in her room in Leningrad. The décor hinted at what had been lost: the once elegant furniture had known better days, a nude by Modigliani still teased, but behind broken glass. An ancient wind-up gramophone conjured up memories of St. Petersburg’s long-silenced bohemia. What we saw was a wreck of a room, a wreck of a life, a wreck of a nation. That Ms. Schull is some three decades older than the Akhmatova of 1938 didn’t really matter: It only emphasized the exhaustion of a woman old before her time and the immense distance between the weary, crumbling figure on stage and the siren she once was.

In 1914, Akhmatova had been a leading figure in the chaotic, fabulous, and wildly innovative avant-garde that was the perverse and paradoxical glory of late imperial Russia. Tall and striking, with a love life to match, she was a scandal, a sensation, and a star. Then war came, and revolution. Her verse darkened, and so did her life. Somehow she hung on through the early years of Soviet rule, almost, but not quite, a “former person,” reduced to near-poverty, writing, writing, writing, brilliant, unacceptable, her poems sometimes too dangerous to be committed to paper for long, dependent for their survival on the memories of a few devoted friends.

And in the room of the banished poet

Fear and the Muse take turns at watch,

And the night comes

When there will be no sunrise.

In one of the play’s most compelling scenes, the audience watched what could never be witnessed, the spectacle of Akhmatova repeating an old anecdote (for the benefit of hidden microphones) to her friend, the loyal Lydia Chukovskaya (Sue Cremin), while Chukovskaya frantically memorized lines of poetry written on a manuscript that would soon have to be burned.

For the most part, Schull’s portrayal (as playwright and actress) of Akhmatova is, understandably enough, admiring. While her Akhmatova is no saint (Schull successfully conveyed a sense of the neediness, neurosis, and self-absorption that were essential aspects of Akhmatova’s personality), it’s difficult not to suspect that she chose to smooth over some of her heroine’s rougher edges. Thus the play has relatively little space for the most enduring of Akhmatova’s affairs, the decade and a half she spent with the art critic Nikolai Punin.

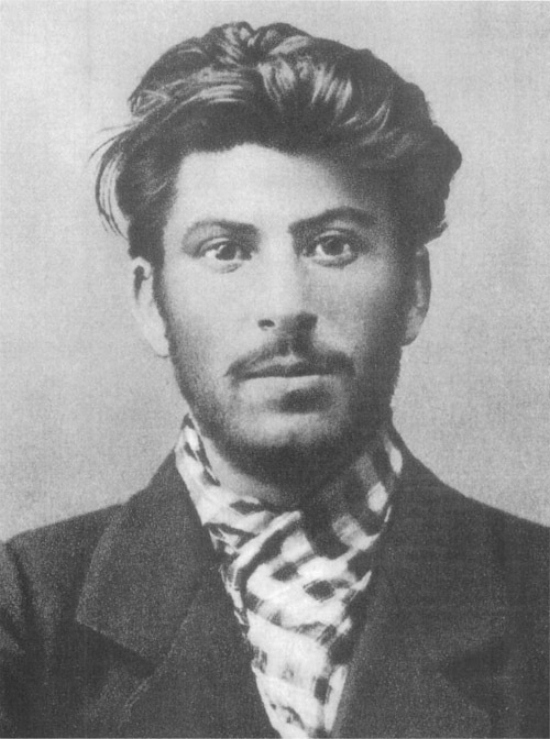

That’s a mistake. A clear grasp of the trajectory of this painful, complicated, and essentially polygamous liaison is crucial to understanding how Akhmatova actually spent most of the 1920s and 1930s, but is likely to have eluded any playgoers not already familiar with the story. The pair finally split up in 1938, not long probably, before the opening scenes of On Naked Soil, although, as too often in this play, the chronology is frustratingly vague. Punin was arrested, for the third time, in 1949. He died in the camps four years later. His Gulag mugshot was just one of many images projected onto the set to flesh out the play’s dialogue, but it’s one that lingers in memory, a lined, sunken face, furious, finished.

No less discreetly, the full nature of Akhmatova’s difficult relationship with her son, Lev, is largely glossed over in favor of the more conventional saga of a determined, grieving mother doing what she could to help her imperiled offspring. In 1938, he had just been re-arrested. It was for Lev that Akhmatova had been standing in those prison queues for those 17 appalling months, desperate for a word, a glimpse, a chance to deliver a parcel of supplies, anything:

Son in irons and husband clay.

Pray. Pray.

But the horror was undoubtedly made worse for Akhmatova by guilt. She knew that Lev had neither forgiven her for sending him away to live with his grandmother for most of his boyhood, nor for what the circumstances of her private life had done to him. This element in his agony, and hers, is underplayed in On Naked Soil. As a result, Lev is reduced to little more than a proxy, an Ivan Denisovitch rather than a character in his own right, an irony that the real-life Lev would have recognized but would have been unlikely to appreciate. That said, his ordeal, even if reduced to something more generic than it deserves, is one of the worst of the nightmares that force their way so savagely into this play and its faded, solitary room. This was underpinned by the way the set design incorporated elements of a prison wall. It was there for use in just one scene but its presence onstage throughout the whole performance served as a pointed illustration of the fact that in the Soviet Union it wasn’t necessary to be in jail to be imprisoned.

After Stalin died, the jailers eased up a touch. Akhmatova was even allowed to travel abroad. Those parts of On Naked Soil set in 1965, about a year before Akhmatova’s death, show her in conversation with Nadezhda Mandelstam (Lenore Loveman), the widow of her old friend, Osip, another poet who perished at the hands of the regime. As in the sections set in 1938, Schull uses the dialogue between two women to recount Akhmatova’s story. These passages, like most of this play, come freighted with memory, and have a certain wistful resonance, but they lacked the intensity of the scenes from 1938. In those, Akhmatova’s interlocutor, Lydia Chukovskaya, a gifted writer who became the poetess’s Boswell, was nervous, tense, and visibly aware that she was herself in danger. Her own husband had been arrested earlier that year and, unknown to her, had already been shot.

Reviewing the play in theNew York Times, Caryn James worried that it became “a virtual recitation of events in [Ahkmatova’s] life, and extraordinary though those events were, simply recalling them isn’t enough to make a drama.” There’s something to that, but not much. The simple retelling of events like these ought to be enough to hold the attention of any audience. Besides, there was very little that was simple about this retelling, not least the fact that many of the words used were Akhmatova’s own, either delivered (often beautifully, if with few traces of Akhmatova’s distinctive incantatory style) as poetry, or embedded into the dialogue, jewels waiting to catch the light.

Buttressed by strong performances from its three actresses, On Naked Soil worked well enough as drama, but it has to be seen for what it is, a chamber piece, not an epic — a reflection, the tiniest piece of a hecatomb. If the play was occasionally overly didactic (with its slide projections and moments of densely packed biographical detail, it had a hint of the college lecture about it), that’s a trivial offense: this is a tale that needs to be kept alive as a memorial — and a warning. Quite what Akhmatova herself would have made of this play, however, I don’t know. One of the subtleties of Schull’s script is the way it makes clear that Akhmatova wanted to be remembered for her lines, not for a life she never truly considered to be her own:

I, like a river,

Have been turned aside by this harsh age.

I am a substitute. My life has flowed Into another channel

And I do not recognize my shores.

She began, and probably would have preferred to remain, as a poetess of the personal, if one captivated also by legend, landscape, and the past. But history had other plans. Akhmatova never fled the country that had abandoned her. Instead she took it upon herself to become a symbol, an inspiration, and a reproach, a reminder of the Russia that might have been, a chronicler of the Russia that was:

I was with my people in those hours,

There where, unhappily, my people were.

There’s a sense of nationhood in those words that Vladimir Putin could never reproduce or, for that matter, even understand.