The Making of a Few Mistakes

Owen Hatherley’s fascinating, if frequently wrong-headed, Landscapes of Communism is a blend of sermon, history and travelogue wrapped into an interpretation of the architecture of communist rule.

Read MoreOwen Hatherley’s fascinating, if frequently wrong-headed, Landscapes of Communism is a blend of sermon, history and travelogue wrapped into an interpretation of the architecture of communist rule.

Read MoreMonetary union in Europe was not a pathway to more efficient markets but, at least in part, a dirigiste attempt to rein them in. The untidiness of Europe’s old foreign-exchange markets must have outraged Brussels’s central planners, but their fluctuations acted as invaluable warning signals to investors and lenders of trouble to come and, in the shape of a currency crisis or two, gave miscreant governments a powerful incentive to take away the punch bowl before it was too late.

Read MoreWhen the established order collapses, those who live among the ruins often take comfort from the hope that someone will turn up to tell them what comes next. With a dysfunctional and humiliated Germany struggling to come to terms with a military defeat that it still did not understand, there was nothing very remarkable about the views of the young, down-at-heel Ph.D. who, in early 1922, complained in an article for his hometown newspaper that “salvation cannot come from Berlin,” the shamed and shameful symbol of old Reich and new Weimar. But all was not lost: “Sometimes it looks as though a new sun is about to rise in the south.”

Read MoreThere was a time, a time not long after history ended, when the narrative was clear. The Soviet Union collapsed, followed by a period too close to chaos for comfort. Finally Putin, picked out from backstage, and promising a firmer hand on the tiller; if no one was sure of the course he would set, how bad could it be? The past was past, after all. In 2006, Peter Pomerantsev, the British son of Soviet-era émigrés, flew into Moscow set on a career in Russian TV. His book tells what happened next.

Read MoreWhen George W. Bush looked Vladimir Putin in the eye, he was, the president famously said, able to get “a sense of his soul.” The president was neither the first nor the last to see what he wanted in this enigmatic, laconic man.

Read MoreCaravan! Van der Graaf Generator! Yes! Genesis! To Englishmen of a certain age, just reading some of these old names will take them back to an era when progressive rock haunted the turntable, songs stretched out endlessly (three minutes would barely be enough for a proper guitar solo), and lyrics—well, they took themselves more seriously than

About halfway through Britain’s long Blair nightmare, I went to two dinners where Boris Johnson was billed as the guest speaker. Each time he was eagerly awaited: a man on the rise, a gifted journalist, an engaging and eccentric television personality, a Tory MP. Each time he was late. When he eventually turned up — all scarecrow hair and unconvincing excuses — he explained that he’d left his notes behind. He pressed on regardless in that blend of Drones Club and High Table that he has made his own. Both speeches were funny, sharp — and more or less identical. Johnson knows, as Winston Churchill knew, that a spontaneous speech takes plenty of preparation. A book by Boris on Winston — first-name politicians both — ought to make sense. Like Churchill, Johnson is phenomenally ambitious, unusually resilient, and remarkably skilled at using showmanship, élan, and his pen to build, refine, and reshape his image.

It’s a shame, then, that The Churchill Factor is not very good. The grand old stories roll on grandly by, but there’s little that’s new for those who know their Churchill, and not enough depth for those who don’t. But if you’re interested in Johnson, this book is well worth a look. If Boris was someone to watch back when I listened to him make one speech two times, he is much more so today. He has since twice won election as mayor of London — no small feat for a Conservative — and is poised to reenter Parliament in the 2015 general election. From there he will be well placed to run for the Tory leadership in the likely event that David Cameron has just led his party off a cliff.

Johnson’s success owes a great deal to the manner in which he has defused his potentially toxic poshness. Like the hapless Cameron, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson went to the wrong school (Eton) and the wrong university (Oxford), and then capped the whole disgraceful gilding by joining the Bullingdon Club, an Oxford gang of the rich and sporadically destructive brought to politically tricky national attention some years ago when an ill-wisher leaked the club’s 1987 photo — a snapshot of archaic finery, Flashman attitude, and Sloane Ranger hair, a photo in which both Cameron and Johnson appeared.

Cameron has tried to deal with this embarrassment of privilege by recasting his public persona (very) gently downscale. The more charismatic Johnson, gambling that Brits take more pleasure in eccentricity than in reverse snobbery, has moved in the opposite direction, putting on a display of wild toff rococo — a bit of Wooster, a spot of Biggles, a touch of Raffles — that has left class warriors too amused to be chippy.

It’s a performance that rests heavily on Johnson’s way with words. His speeches are punctuated by slang, dated terminology, and madcap verbal construction. An accusation of infidelity was famously, if inaccurately, dismissed as an “inverted pyramid of piffle.” But what works in a sound bite palls over the course of a book. Tootling, monstering, wonky, squiffily, tosser, prang, perv, titfer, snortingly, bonkers, bunging — crikey, Boris, hold the shtick already. Unnecessary adjectives and superfluous adverbs run wild. Metaphors meander. A promising description of Churchill’s house — crammed with researchers, writers, and secretaries — as “one of the world’s first word processors . . . a gigantic engine for the generation of text” dragged on so long that all I wanted was the delete button. To be sure, there are splendid moments (“the French were possessed of an origami army: they just kept folding”), but they are swamped by verbosity.

So it’s ironic that the best section of the book is Johnson’s superb analysis of how Churchill’s oratory was put together, what it was meant to convey, and why it worked as well as it did. Sadly, Johnson himself ignores two key Churchillian tricks — short words over long, “Anglo-Saxon pith” over intruders with Latin and Greek origins — burdening the readers of this book with such treats as chiasmus, philoprogenitive, and eirenic, words that probably played little part in the small talk of Alfred the Great.

But these ten-guinea words are sly demonstrations of erudition, deployed for political, not literary, effect. Boris may play Wooster to beguile the plebs, but he wants them to understand that he is no upper-class twit. At the same time, he needs his audiences to feel that he is an inclusive sort of fellow, with them if not necessarily of them. So he brings his readers alongside him on trips to the sacred sites — to Chartwell, to the House of Commons, to kind Nurse Everest’s grave — while throwing in glimpses of a life that he invites them to share, if only by proxy: lunch at the Savoy, a birthday bash for a hedge-fund “king” at Blenheim Palace. Condescending, yes, but cleverly disguised. Only rarely does the mask slip, and the text sprouts tics more typical of history books written for the late-Victorian nursery: “Those were the days, you see, when there was no moral pressure on MPs to have a ‘home’ in the constituency.”

“You see”? Well, I suppose I do. Thank you, sir.

Notionally, Johnson has written this book to revive ebbing memories of Churchill and to remind his readers that, whatever some cruder Marxists might have to say about history’s being driven by “vast and impersonal economic forces,” one man can make a difference. Based primarily on a fine retelling of the events of 1940, Johnson makes a strong, if unsurprising, case that Churchill was such a man.

But Boris’s real objective in writing about Churchill is to promote Boris. Wisely, he doesn’t try to push Churchill comparisons — hosting the London Olympics doesn’t quite rank with seeing off Hitler — but there’s enough there for a satisfactory subliminal message. So Johnson tells the story of a man comfortable in his unorthodoxies, a statesman who was larger than life, and, like a certain twice-elected mayor of London that I could mention, larger than party.

In recent years, Johnson has positioned himself as offering a more robust, less politically correct version of David Cameron’s “modernized” conservatism, more libertarian, not so committed to environmentalist piety, pro-immigration (for its purported qualities as an agent of economic growth), and a booster of London’s cosmopolitanism, too, but not so respectful of multiculturalist orthodoxy. Johnson portrays Churchill, not unreasonably, as an early-20th-century Whig, an optimist, a Progressive of sorts.

But the old imperialist is not safely pigeonholed. Johnson defends his hero against the accusation that he was a warmonger and — as he should — places some of Churchill’s rougher views within the context of his times. Occasionally (not as uncharacteristically as fans of the allegedly plain-speaking Johnson like to believe), Boris simply dodges the issue: There is nothing on Churchill’s response to the Bengal famine of 1943, startlingly callous then and now.

Johnson — clearly conscious that times have moved on for the island race — takes care to signal that, despite his obvious admiration for Churchill, he himself is no reactionary. He distances himself from some instances of the more “unpasteurized” Churchill, but not too far. The last lion is still idolized by many of those who will be picking the next Conservative leader, an election evidently on Johnson’s mind. Why else tread quite so carefully on the question of Churchill’s complicated views on a united Europe, that most treacherous of Tory topics?

But tread carefully Johnson does. He has his eyes on the prize. Churchill would have understood.

I first visited Estonia—or more specifically, its capital, Tallinn—in August 1993, two years after the small Baltic state regained its independence after nearly half-a-century of Soviet occupation. Tallinn was in the process of uneasy, edgy transformation. The Soviet past was not yet cleanly past. It was still lurking in the dwindling Russian military bases. It was still visible in the general shabbiness, in the rhythms of everyday life, and, above all, in the presence of the large Russian settler population, a minority that Vladimir Putin now eyes hopefully, if not necessarily realistically, for its troublemaking potential.

Totalitarian colonial rule had been replaced by a national democracy, the ruble had been succeeded by the kroon, and free-market reformers were at the helm; but the new government was operating in the rubble of the command economy. There was no spare cash to smooth the transition to capitalism. Inflation had exceeded 1,000 percent during the course of the previous year, savings had been wiped out, the old Soviet enterprises were dying, and the welfare net was fraying.

Yet in Tallinn there was a discernible sense of purpose, buttressed by memories of the prosperous nation prewar Estonia had been. What people wanted, I was told, was a “normal life.” That was a phrase that could be heard all over the former Eastern Bloc in those days, a phrase that damned the Soviet experience as an unwanted, unnatural interruption and resonated with dreams of that elusive Western future. Life was tough in Tallinn, but there were hints of better times to come. If the country was to be rebuilt, this was where the turnaround was taking shape.

But Sigrid Rausing went somewhere else in 1993, to a place far from the hub of national reconstruction, a place where the inhabitants had little idea of what could or should come next, a bleak place—poor, even by the demanding standards of post-Soviet Estonia—where nationhood was misty and visions of the future were still obscured by the wreckage of an alien utopia. Rausing, a scion of one of Sweden’s richest families, was a doctoral student in social anthropology. To gather material for her thesis, she spent a year on the former V. I. Lenin collective farm on Noarootsi, a remote peninsula on the western Estonian coast.

Noarootsi had once been inhabited by members of the country’s tiny Swedish minority, most of whom had been evacuated to the safety of their ancestral homeland by Estonia’s German occupiers shortly before the Red Army returned in 1944. The final minutes before their departure were caught on film: the exiles-to-be assembled on a beach, Red Cross representatives mingling with smiling SS officers. Baltic history is rarely straightforward.

Rausing’s thesis formed the basis of her History, Memory, and Identity in Post-Soviet Estonia: The End of a Collective Farm, an academic work published by Oxford University Press 10 years ago. This was never a book destined to top the bestseller lists, but for anyone able to weather the clouds of jargon that drift by—“the effect was to emphasize the experience of oppositions in the form of a homology”—it offers a sharp, intriguing, and unexpectedly wry portrait of what Rausing refers to as the “particular post-Soviet culture of 1993-94, the culture of transition and reconstruction,” a culture that no longer exists.

Rausing has now reworked the topic of her time in Noarootsi into Everything Is Wonderful, a personal, intimate account of that year in which she largely dispenses with academic analysis—indeed, there are moments when she pokes gentle fun at its absurdities—and gives her considerable lyrical gifts free rein. Graduate-school prose now finds itself transformed into passages of austere beauty. They describe a landscape that reminds her of Sweden, only “deeper, vaster, and sadder”; more than that, they portray a people adrift. There is something of dreaming in her writing, images that haunt. Spring returns, and

the children were outside again, playing and shouting in the long twilight, until there was an almost deafening din echoing between the blocks of flats. One day someone burnt the old brown grass strewn with rubbish between the blocks, and the children kept up their own private fires deep into the night.

There is a subplot too, tense and awkward, sometimes expressed in not much more than a hint, that surrounds the position of Rausing herself, an attractive thirty-something Swedish heiress inserted into this exhausted husk of a community and, for a while, lodging with the heavy-drinking, possibly/probably lecherous Toivo and his long-suffering wife, Inna. Ingmar Bergman, your agent is on the line.

That’s not to say that Rausing neglects the broad themes of her academic research. As she notes, the two books “overlap to some degree,” and they have to. Without repeating some of the background covered in the first volume, isolated, depopulated Noarootsi—with its Soviet dereliction, abandoned watch-towers (the peninsula had been in a restricted border zone), emptied homesteads, and taciturn, enigmatic inhabitants scarred by alcoholism and worse and speaking a language of a complexity Rausing struggled to grasp—would have seemed like nothing so much as the setting for a piece of post-apocalyptic gothic. So Rausing provides a brief, neatly crafted, and necessary guide to Estonia’s difficult and troubled history, neglecting neither the obvious horrors nor the subtler atrocities, such as the attempted cultural annihilation represented by the wholesale destruction of Estonian literature. Tallinn Central Library lost its entire collection of books—some 150,000 of them—between 1946 and 1950.

Sometimes, traces of that history—forbidden for so long—come crashing through the silence. Ruth, 76, a Seventh-Day Adventist, tipped by tyranny into something more unhinged than eccentricity, hands Rausing a handwritten retelling of her life: “Devilish age, sad age. Schoolchildren also spies . . . life as leprosy.” But Everything Is Wonderful is a book in which the story lies mainly beneath the surface. Old ways linger on amid new realities. There is a new cooperative store, but the old Soviet shop hangs on, “selling household stuff as well as some food, pots and pans, exercise books, shoes if they got a consignment, and ancient Russian jars of jams and pickles with rusty lids and falling-off labels.”

Throughout the brutal winter, heating is intermittent. Heating bills are no longer subsidized, but the majority of villagers “patiently” pay them nonetheless. New habits creep in. Empty Western bottles and other packaging are displayed in apartments, demonstrations of “a connection with the West, a way of expressing the new normal”—that word again, that “normal” in which most had yet to find their feet. Meanwhile, Swedes bring hand-me-down help and the suspicion that they might be looking to reclaim a long-lost family home.

Rausing is a participant in this drama. We learn of her fears, her loneliness, of her wondering what she is doing in this distant Baltic corner, and of her small pleasures, too (“the tipsy sweet happiness of strawberry liqueur”). But she is a spectator as well, and a perceptive one, not least when it comes to the profoundly uncomfortable relationship between Estonians and the Russian minority. The latter are resented as colonists, yet caricatured in terms that remind Rausing of the “natives” of the “colonial imagination: happy-go-lucky, hospitable people lacking industry, application, and predictability.” She dines in a restaurant in a nearby town, where “the atmosphere was a little strained between a Russian group of guests and the few Estonians in the room.” Later, Rausing learns that the “only” Russians living in the “comfortable Estonian part of town” are deaf and dumb; they are “outside language,” as she puts it, and thus able (she theorizes) to “assimilate . . . through muteness.”

That sounds extreme, but the scars of the past were still very raw back then. Sometime in the mid-1990s, I watched a senior member of the Estonian government bluntly explain the facts of Estonia’s (to borrow a Canadian phrase) twin solitudes to a delegation of Swedish investors. There was, he said, little overt trouble between ethnic Estonians and the country’s Russians, but there was little contact either: “We don’t get on.”

Rausing’s tone is quiet, often wistful, marred only by interludes of limousine liberalism—apparently there was something “liberating” in the way the locals didn’t care too much about their possessions, which is easy enough, I imagine, when those possessions were, for the most part, Soviet junk—including an element of disdain for the market reforms that were to work so well for Estonia. The prim pieties of Western feminism also make an unwelcome appearance. Watching a pole dancer in a rundown resort town summons up concerns over “objectification,” but Rausing’s response to reports of a topless car wash in Tallinn is endearingly puzzled and—so Swedish—practical: “Really strange, particularly given the Estonian climate.”

But this should not detract from Rausing’s wider achievement. Her book is the last harvest yielded up by that old collective farm, and the finest.

Richard Ropner (Harrow), Royal Machine Gun Corps

On August 3, 1914, twenty-two of England’s best public school cricketers gathered for the annual schools’ representative match. The game ended the following evening. Britain’s ultimatum to Germany expired a few hours later. Seven of those twenty-two would be dead before the war was over. Anthony Seldon and David Walsh’s fine new history of the public schools and the First World War bears the subtitle “The Generation Lost” for good reason.

Britain neither wanted nor was prepared for a continental war. Its armed forces were mainly naval or colonial. The regular army that underwrote that ultimatum was, in the words of Niall Ferguson, “a dwarf force” with “just seven divisions (including one of cavalry), compared with Germany’s ninety-eight and a half.”

Britain’s more liberal political traditions, so distinct then—and now—from those of its European neighbors, had rendered peacetime conscription out of the question, but manpower shortages during the Boer War and growing anxiety over the vulnerability of the mother country itself led to a series of military reforms designed to toughen up domestic defenses. These included the consolidation of ancient yeomanry and militias into a Territorial Force and Special Reserve. The old public-school “rifle corps,” meanwhile, were absorbed into an Officers’ Training Corps and put under direct War Office control.

Most public schools signed up for this, and by 1914 most had made “the corps” compulsory. Some took it seriously. Quite a few did not. Stuart Mais, the author of A Public School in Wartime (1916), wrote that Sherborne’s prewar OTC was seen as “a piffling waste of time . . . playing at soldiers” that got in the way of cricket. Two decades later, Adolf Hitler cited the OTC to a surprised Anthony Eden (then Britain’s foreign secretary) as evidence of the militarization of Britain’s youth. It “hardly deserved such renown,” drily recalled Eden (in his unexpectedly evocative Another World 1897–1917), “even though the light grey uniforms with their pale blue facings did give our school contingent a superficially Germanic look.”

And yet this not-very-military nation saw an astonishing response to the call for volunteers to join the fight. By the end of September 1914 over 750,000 men had enlisted. But where were the officers to come from? A number of retired officers returned to the colors, and the Territorials boasted some men with useful experience, but these were not going to be close to sufficient numbers. The army turned to public-school alumni to fill the gap. In theory, this was because these men had enjoyed the benefit of some degree of military training, however inadequate, with the OTC, but in truth it was based on the belief of those in charge, themselves almost always former public schoolboys, that these chaps would know what to do. Looked at one way, this was nothing more than crude class prejudice; looked at another, it made a great deal of sense. In the later years of the war, many officers (“temporary gentlemen” in the condescending expression of the day) of humbler origins rose through the ranks, but in its earlier stages the conflict was too young to have taught the army how best to judge who would lead well. In the meantime, Old Harrovians, Old Etonians, and all those other Olds would have to do.

To agree that this was not unreasonable implies a level of acceptance of the public school system at its zenith utterly at odds with some of the deepest prejudices festering in Britain today. British politics remain obsessed with class in a manner that owes more to ancient resentments than any contemporary reality. A recent incident, in which a columnist for the far left Socialist Worker made fun of the fatal mauling of an Eton schoolboy by a polar bear (“another reason to save the polar bears”), is an outlier in its cruelty, but it’s a rare week that goes by in which a public school education is not used to whip a Tory cur, as David Cameron (Eton) knows only too well.

Under the circumstances it takes courage to combine, as Seldon and Walsh do, a not-unfriendly portrait of the early twentieth-century public schools (it should be noted that both men are, or have been, public schoolmasters) with a broader analysis that implies little sympathy for the sentimental clichés that dominate current British feeling—and it is felt, deeply so—about the Great War: Wilfred Owen and all that. It is not necessary to be an admirer of the decision to enter the war or indeed of how it was fought (I am neither) to regret how Britain’s understanding of those four terrible years has been so severely distorted over the past decades. Brilliantly deceptive leftist agitprop intended to influence modern political debate has come to be confused with history.

Oh! What a Lovely War smeared the British establishment of the 1960s with the filth of Passchendaele and the Somme. Similarly, the caricature of the war contained in television productions such as Blackadder Goes Forth (1989) and The Monocled Mutineer (1986) can at least partly be read as an angry response to Mrs. Thatcher’s long ascendancy. Coincidentally or not, the late 1980s also saw the appearance of The Old Lie: The Great War and the Public-School Ethos by Peter Parker. For a caustic, literary, and intriguing—if slanted—dissection of these schools’ darker sides, Parker’s book is the place to go.

Seldon and Walsh offer a more detailed and distinctly more nuanced description of how these schools operated, handily knocking down a few clichés on the way: There were flannelled fools aplenty, but there was also the badly wounded Harold Macmillan (Eton), “intermittently” reading Aeschylus (in Greek) as he lay for days awaiting rescue in a shell hole. Aeschylus was not for all, but a glance at the letters officers wrote from the front is usually enough to shatter the myth of the ubiquitous philistine oaf. There was much more to the public schools than, to quote Harrow’s most famous song, “the tramp of the twenty-two men.”

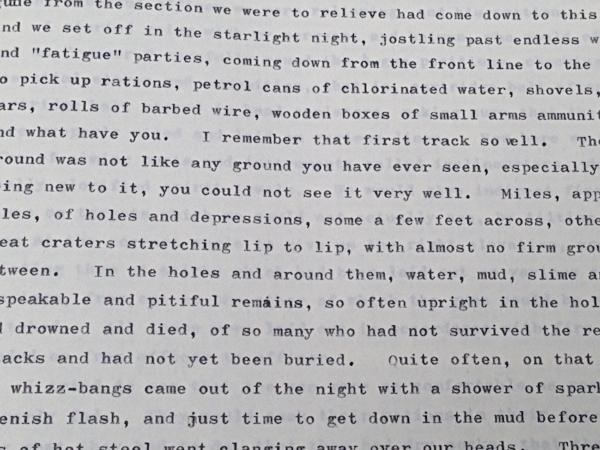

But however harsh a critic he may be (“that men died for an ethos does not mean that the ethos was worth dying for”), Parker is too honest a writer not to acknowledge the good, sometimes heroic, qualities of these hopelessly ill-trained young officers and the bond they regularly forged across an often immense class divide with the troops that they led. “I got to know the men,” wrote my maternal grandfather Richard Ropner (Harrow, Machine Gun Corps) in an unpublished memoir half a century later, “I hope they got to know me.” In many such cases they did. It is tempting to speculate that such bonds (easier to claim, perhaps, de haut than en bas) may have been more real in the eyes of the commanders than of the commanded, but there is strong evidence to suggest that there was nothing imaginary about them. Men died for their officers. Officers died for their men.

My grandfather owned a set of memorial volumes published by Harrow in 1919. Each of the school’s war dead is commemorated with a photograph and an obituary. It is striking to see how frequently the affection with which these officers—and they almost all were officers—were held by their men is cited. Writing about Lieutenant Robert Boyd (killed at the Somme, July 14, 1916, aged twenty-three), his company commander wrote that Boyd’s “men both loved him and knew he was a good officer—two entirely different things.” This subtle point reflects the way that the public school ethos both fitted in with and smoothed the tough paternalism of the regular army into something more suited to a citizen army that now included recruits socially, temperamentally, and intellectually very different from that rough caste apart, Kipling’s “single men in barricks.”

The public schools relied heavily on older boys to maintain a regime that had come a long way from Tom Brown’s bleak start. This taught them both command and, in theory (Flashman had his successors), the obligations that came with it. That officers were expected both to lead and care for their men was a role for which they had thus already been prepared by an education designed, however haphazardly, to mold future generations of the ruling class. Contrary to what Parker might argue, these schools had not set out to groom their pupils for war. But the qualities these institutions taught—pluck, dutifulness, patriotism, athleticism (both as a good in itself and as a shaper of character), conformism, stoicism, group loyalty, and a curious mix of self-assurance and self-effacement—were to prove invaluable in the trenches as was familiarity with a disciplined, austere, all-male lifestyle.

There was something else: The fact that many of these men had boarded away from home, often from the age of eight, and sometimes even earlier, meant that they had learned how to put on a performance for the benefit of those who watched them. A display of weakness risked transforming boarding school life into one’s own version of Lord of the Flies. That particular training stayed with them on the Western Front: “I do not hold life cheap at all,” wrote Edward Brittain (Uppingham), “and it is hard to be sufficiently brave, yet I have hardly ever felt really afraid. One has to keep up appearances at all costs even if one is.” It was all, as Macmillan put it, part of “the show.”

There are countless examples of how stiff that upper lip could be, but when Seldon and Walsh cite the example of Captain Francis Townend (Dulwich), even those accustomed to such stories have to pause to ask, who were these men?: “Both legs blown off by a shell and balancing himself on his stumps, [Townend] told his rescuer to tend to the men first and said that he would be all right, though he might have to give up rugby next year. He then died.”

Pastoral care was all very well, but the soldiers also knew that, unlike the much-resented staff officers, their officers took the same, or greater, risks that they did. This was primarily due to the army’s traditional suspicion that the lower orders—not to speak of the raw, half-trained recruits who appeared in the trenches after 1914—could not be trusted with anything resembling responsibility, but it also reflected the officers’ own view of what their job should be. And so, subalterns (a British army term for officers below the rank of captain), captains, majors, and even colonels led from the front, often fulfilling, particularly in the case of subalterns, a role that in other armies would be delegated to NCOs. The consequences were lethal. Making matters worse, the inequality between the classes was such that officers were on average five inches taller than their men, and, until the rules were changed in 1916, they always wore different uniforms too. The Germans knew who to shoot. The longer-term implications of this cull of the nation’s elite may have been exaggerated by Britons anxious to explain away their country’s subsequent decline, but the numbers have not: some 35,000 former public schoolboys died in the war, a large slice of a small stratum of society.

Roughly eleven percent of those who fought in the British army were killed, but, as Seldon and Walsh show, the death rate among former public schoolboys (most of whom were officers) ran at some eighteen percent. For those who left school in the years leading up to 1914 (and were thus the most likely to have served as junior officers) the toll was higher still. Nearly forty percent of the Harrow intake of the summer of 1910 (my grandfather arrived at the school the following year) were not to survive the war. Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War (2010) by John Lewis-Stempel is an elegiac, moving, and vivid account of what awaited them. Lewis-Stempel explains his title thus: “The average time a British Army junior officer survived during the Western Front’s bloodiest phases was six weeks.”

To Lewis-Stempel, a fierce critic of those who see the war as a pointless tragedy, the bravery and determination of these young officers made them “the single most important factor in Britain’s victory on the Western Front,” a stretch, but not an altogether unreasonable one, and he is not alone in thinking this way. The British army weathered the conflict far better—and far more cohesively—than did those of the other original combatants, and effective officering played no small part in that.

Lewis-Stempel attributes much of that achievement to the “martial and patriotic spirit” of the public schools, a view of those establishments with which Parker would, ironically, agree, but that is to muddle consequence with cause. Patriotic, yes, the schools were that, as was the nation—being top dog will have that effect. But, like the rest of the country, they were considerably less “martial” than Britain’s mastery of so much of the globe would suggest. A public school education may have provided a good preparation for the trenches, but it did not pave the way to them. That so many alumni came to the defense of their country in what was seen as its hour of need ought not to form any part of any serious indictment against the schools from which they came. That they sometimes did so with insouciance and enthusiasm that seems remarkable today was a sign not of misplaced jingoism, but of a lack of awareness that, a savage century later, it’s difficult not to envy.

And when that awareness came, they still stuck it out, determined to see the job done. Seldon and Walsh write that “It was the ability . . . to endure which underpinned the former public schoolboys’ leadership of the army and the nation.” Perhaps it would have been better if they had had been less willing to endure and more willing to question, but that’s a different debate. To be sure, there was plenty of talk of the nobility of sacrifice—and of combat—but, for the most part, that was evidence not of a death wish or any sort of bloodlust, but of the all too human need to put what they were doing, and what they had lost, into finer words and grander context.

And that they clung so closely to memories of the old school—to an extent that seems extraordinary today—should come as no surprise. These were often very young men, often barely out of their teens. School, especially for those who had boarded, had been a major part of their lives, psychologically as well as chronologically. “School,” wrote Robert Graves (Charterhouse), “became the reality, and home life the illusion.” And now its memory became something to cherish amid the mad landscape of war.

They wrote to their schoolmasters and their schoolmasters wrote to them. They returned to school on leave and they devoured their school magazines. They fought alongside those who had been to the same schools and they gave their billets familiar school names. They met up for sometimes astoundingly lavish old boys’ dinners behind the lines, including one attended by seventy Wykehamists to discuss the proposed Winchester war memorial. The names of three of the subalterns present would, Seldon and Walsh note, eventually be recorded on it.

So far as is possible given what they are describing, these two authors tell this story dispassionately. Theirs is a calm, thoroughly researched work, lacking the emotional excesses that are such a recurring feature of the continuing British argument over the Great War. That said, this book’s largely uninterrupted sequence of understandably admiring tales could have done with just a bit more counterbalance. For that try reading the recently published diaries written in a Casualty Clearing Station by the Earl of Crawford (Private Lord Crawford’s Great War Diaries: From Medical Orderly to Cabinet Minister) with its grumbling about “ignorant and childish” young officers arousing “panic among the men [with] their wild and dangerous notions.”

Doubtless the decision by Captain Billy Neville (Dover College) to arrange for his platoons to go over the top on the first day of the Somme kicking soccer balls is something that Crawford would have included amongst the “puerile and fantastic nonsense” he associated with such officers. Seldon and Walsh, by contrast, see this—and plausibly so—not as an example of Henry Newbolt’s instruction to “Play up! play up! and play the game!” being followed to a lunatic degree, but rather as an astute attempt by Neville to give his soldiers some psychological support. “His aim was to make his men, who he knew would be afraid, more comfortable.” Better to think of those soccer balls than the enemy machine guns waiting just ahead. Nineteen thousand British troops were killed that day, including Neville. He was twenty-one.

Crawford was a hard-headed, acerbic, and clever Conservative, but occasionally his inner curmudgeon overwhelmed subtler understanding, as, maybe, did his location behind the lines, fifteen miles from where these officers shone. Nevertheless, one running theme of his diaries, the luxuries that some of them allowed themselves (“yesterday a smart young officer in a lofty dogcart drove a spanking pair of polo ponies tandem past our gate”) touches on a broader topic—the stark difference in the ways that officers and men were treated—that deserves more attention than it gets in Public Schools and the Great War. Even the most junior officers were allocated a “batman” (a servant). They were given more leave, were paid a great deal more generously, and, when possible, were fed far better and housed much more comfortably than their men. Even in a more deferential age, this must have rankled. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Parker dwells on this issue in more detail than Seldon and Walsh, but, fair-minded again, agrees that what truly counted with the troops was the fact that “when it came to battle [the young officers’] circumstances were very much the same as their own.”

They died together. And they are buried together, too, not far from where they fell. As the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission explained, “in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the officers will tell you that, if they are killed, they would wish to be among their men.”

A century later, that’s where they still are.

Richard Ropner - Random Recollections (unpublished - 1965)

In the months leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution, Joseph Stalin was, recalled one fellow revolutionary, no more than a “gray blur.” The quiet inscrutability of this controlled, taciturn figure eventually helped ease his path to some murky place in the West’s understanding of the past, a place where memory of the horror he unleashed was quick to fade. Pete Seeger sang for Stalin? Was that so bad?

This bothers Paul Johnson, the British writer, historian and journalist. Hitler, he notes with dry understatement, is “frequently in the mass media.” Mao’s memory “is kept alive by the continuing rise . . . of the communist state he created.” But “Stalin has receded into the shadows.” Mr. Johnson worries that “among the young [Stalin] is insufficiently known”; he might have added that a good number of the middle-aged and even the old don’t have much of a clue of who, and what, Stalin was either.

Mr. Johnson’s “Stalin: The Kremlin Mountaineer” is intended to put that right. In this short book he neatly sets out the arc of a career that took Soso Dzhugashvili from poverty in the Caucasus to mastery of an empire. We see the young Stalin as an emerging revolutionary, appreciated by Lenin for his smarts, organizational skills and willingness to resort to violence. Stalin, gushed Lenin, was a “man of action” rather than a “tea-drinker.” Hard-working and effective, he was made party general secretary a few years after the revolution, a job that contained within it (as Mr. Johnson points out) the path to a personal dictatorship. After Lenin’s 1924 death, Stalin maneuvered his way over the careers and corpses of rivals to a dominance that he was never to lose, buttressed by a cult of personality detached from anything approaching reason.

Mr. Johnson does not stint on the personal details, Stalin’s charm (when he wanted), for example, and dark humor, but the usual historical episodes make their appearance: collectivization, famine, Gulag, purges, the Great Terror, the pact with Hitler, war with Hitler, the enslavement of Eastern Europe, Cold War, the paranoid twilight planning of fresh nightmares and a death toll that “cannot be less than twenty million.” That estimate may, appallingly, be on the conservative side.

Amid this hideous chronicle are unexpected insights. Lenin’s late breach with Stalin, Mr. Johnson observes, was as much over manners as anything else: “a rebuke from a member of the gentry to a proletarian lout.” And sometimes there is the extra piece of information that throws light into the terrible darkness. Recounting the 1940 massacre of Polish officers at Katyn, Mr. Johnson names the man responsible for organizing the shootings—V.M. Blokhin. He probably committed “more individual killings than any other man in history,” reckons Mr. Johnson. Ask yourself if you have even heard his name before.

To be sure, Mr. Johnson’s “Stalin” will not add much new to anyone already familiar with its subject’s grim record. It is a very slender volume—a monograph really. Inevitably in a book this small on a subject this large, the author paints with broad strokes, sweeping aside some accuracy along the way. Despite that, this book makes a fine “Stalin for Beginners.”

As Mr. Johnson’s vivid prose rolls on, the gray blur is replaced by a hard-edged reality. Stalin’s published writings were turgid, and he was no orator, but there was nothing dull about his intellect or cold, meticulous determination. As for his own creed, Mr. Johnson regards him as “a man born to believe,” one of the Marxist faithful, and maybe Stalin, the ex-seminarian, was indeed that: Clever people can find truth in very peculiar places.

But what he was not, contrary to the ludicrous, but persistent, myth of good Bolshevik intentions gone astray, was the betrayer of Lenin’s revolution. As Mr. Johnson explains, Stalinist terror “was merely an extension of Lenin’s.” Shortly before the end of his immensely long life, Stalin’s former foreign minister (and a great deal else besides), Vyacheslav Molotov, reminisced that “compared to Lenin” his old boss “was a mere lamb.” Perhaps even more so than those of Stalin, Lenin’s atrocities remain too little known.

Over to you, Mr. Johnson.